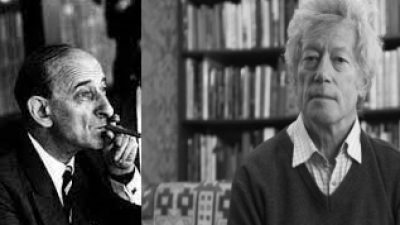

Raymond Aron and Roger Scruton hardly shared anything besides the English Channel. However, in retrospect, with the passing of time, we can see how the spirit of the times placed them on the same side of the barricade. The most important factor that unites them – over and above their differences – by bonds of brotherhood, not so much of blood as of ink, on the battlefield created from the pages of books, journalistic commentaries and university buildings, has been the common defence against a massive attack, often unjustified as to the substance, by their leftist intellectual contemporaries.

Why were they so different? They originated from different schools of doing science. Roger Scruton was a reticent representative of the British school of philosophy, writing concisely but bluntly and accurately. Raymond Aron was a virtuoso at producing great philosophical and sociological treatises. Before the 1938 publication of his doctoral dissertation in philosophy entitled Introduction à la philosophie de l’histoire. Essai sur les limites de l’objectivité historique (Introduction to the philosophy of history: an essay on the limits of historical objectivity), as early as in 1935 La sociologie allemande contemporaine (German Sociology) was published. The French scholar would later complain that he had never heard of Tocqueville or Weber at L’ENA (Widz i uczestnik 25). Scruton categorically, and perhaps too hastily, classified sociology as a futile and unexpected field, forming a mainstay of leftist thought (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 26). The Frenchman was an intellectual and a columnist writing political commentaries (Le Figaro, L’Express). Many subtle differences between them could be listed, such as the fact that Scruton was also a novelist and composer, while Aron was primarily a “committed observer”. While Scruton is described as “the leading theorist of the political philosophy of the new conservatives” (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy), Raymond Aron would describe himself as the last representative of old (i.e. conservative) liberalism:

In an interview with Aron, J.-L. Missika asked him a question directly: Are you the last liberal? Aron replied: No, I am not. There are many people today who want to join me. I might even be fashionable to some extent. (Widz i uczestnik 315)

This response, when presented to the contemporary reader (after the blows inflicted on neoliberalism by the 2009 crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic), cannot be left without outlining the context in which it was provided. Earlier on (not long before his death in 1983), Aron defined precisely what he meant by the sarcastically used term “fashionable”. To the question posed by Dominique Wolton Do you think the values of Western democracy remain attractive at the end of the 20th century? the French intellectual replied:

Despite the fact that Europeans or Westerners in general made conquests and were as cruel as any conquerors, they still left the peoples they once conquered something they wanted to keep. (...) (R)egardless of the political systems that have arisen, many societies that were once conquered and not treated well by the West have retained a longing for liberal systems. The best proof is that quite a few countries that do not want or cannot maintain democratic institutions use our terminology. Perhaps they have also inherited our flaws. Yet, by using our language, our concepts, they perhaps demonstrate that the West is a bit different from most other conquerors. In spite of everything, we have instilled in these countries something which does not lose its value and which nevertheless justifies my belief in the future of Europe, even though the foundation of this belief is to be found in feelings rather than in irrefutable facts (Widz i uczestnik 315).

I would like to leave it to the reader’s judgment whether these are 20th-century miasmas of an old intellectual, obsolete in an age of a counter-culture overthrowing old monuments and the seemingly inviolable foundations of Western society (Aron already experienced this in 1968), or whether the reader will find hope in them for the future of the West. Aron was a generation older than Scruton. Hence, they confronted the same experiences differently. The French Social Revolution of May 1968, for example, was less shocking for Aron, familiar with the pre-war European anti-Semitism (including Hitler’s Germany) and the horrors of the Second World War, than university riots for Scruton, who was shaken by them. The perspective of age difference is a significant variable too.

When was it, May 1968? The week of student protests. This was followed by two weeks of strikes that gradually covered almost all of France and paralyzed the economic life of the country (247).

It is noteworthy that Raymond Aron was considered the main opponent of the revolting students. This is an oversimplification that falsifies the reality. Yes, he criticized the riots as an unacceptable form of destabilization of the state, but he agreed with some of the postulates, or at least understood them (Widz i uczestnik 247-254). He regarded being described as a symbol of the old university as a misunderstanding. After all, in 1960 he offended respectable professors by criticizing, for example, the necessity of going through the post-doctoral (habilitation) procedure (which he himself obtained). However, in May 1968, when the old academics who did not like him were treated unworthily by the demonstrators, he stood up for the academics. He wanted French universities to be reformed rather than destroyed. Aron’s actual attitude to the events in France in May 1968 was revealed in his conversation with Kojève:

Whenever something was happening in France, Kojève would call me right away. He told me: ‘It’s not a revolution, it can’t be a revolution. There can be no revolution without killing. Nobody’s killing anybody. Students are taking to the streets. They are shouting at the police that they’re the SS, but this SS isn’t killing anyone, it’s not serious, it’s no revolution’ (Widz i uczestnik 251).

The French students, strictly speaking, shouted and wrote CRS = SS on the walls. The acronym CRS stands for Companies Républicaines de Sécurité (Companies for Republican Security), mobile units forming the general reserve of the national police (Police national) and acting as prevention squads both in 1968 and in 2018-2021 (the yellow vests protests) to suppress demonstrations and patrol dangerous neighbourhoods.

When Scruton was born in 1944, Aron was already a well-known journalist and book author. From 1940 he had been associated with the Free French community. When Raymond Aron passed away in 1983, in the glory of a great intellectual who was almost always right, a few years later Scruton witnessed the disintegration of the post-Yalta order and the geopolitical changes of the 1990s – moral, social and cultural alike. In addition to being attacked by the Left, both intellectuals created scientific descriptions in essay form. Scruton wrote philosophical essays, and Aron – sociological ones. Moreover, both were accused of financial opportunism. The French scholar was to be paid by the Congress for Freedom and Culture created in 1950 in Berlin (in French: Congrès pour la liberté de la culture; in German: Kongress für Kulturelle Freiheit) and financed by the CIA. The British intellectual was accused in the early 2000s that his articles written in defence of smoking and drinking were sponsored with large sums of money by JTI.

Aron and Scruton – human shields for criticism by the leftist intellectuals.

In writing about the cursed intellectuals, one must begin with Scruton’s shocking quote from the introduction to Thinkers of the New Left:

"Almost all of the reviews of this book were written by people with left-wing beliefs; they all decided that they were not bound by the normal rule of objectivity. They sincerely believe that an author who proves the intellectual fraud of socialism has already transgressed against the etiquette to such an extent that he can in good conscience be excluded from the framework of cultural discussion".

Typical of this reaction was a letter to the publisher (Longman) from dr Michael Shortland, a lecturer in philosophy at Oxford University. (Shortland is also the reviews editor of Radical Philosophy, a journal advocating socialist ideas.) 'I can say', writes Shortland, ‘that I, along with many colleagues in the local (i.e. Oxford) Philosophy Department, have been thinking deeply about whether to write a review of “Thinkers of the New Left”. Everyone, without exception, felt that this flimsy, trashy book did not deserve to be advertised. You could judge the extremely unfavourable tone of the review of this book already then. However, I am concerned to tell you that many other Oxford colleagues feel that Longman – an otherwise highly reputed publishing house – has been tainted by its association with Scruton’s work. He further repeats explicitly the veiled threat contained in the last sentence. I hope that the negative reactions generated by this particular publishing venture may make Longman think more carefully about its policy in the future.” (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 7)

Roger Scruton accurately chose to quote from the review of his book such annoyingly meaningless and ad personam criticism, shocking the reader from the very beginning. It is hard to find a better summary of this unfair opinion than Scruton’s:

It is fair to say that the reviewers failed to pay attention to the arguments in this book, and instead focused on its tone (7-8)

This bitter statement by the British philosopher is perfectly matched by Stuart Hall’s opinion, who describes the tone of Scruton’s argumentation as a bad-faith polemic characterized by a lack of intellectual curiosity (8). What is striking in these reviews is the absolute lack of even an attempt at scientific falsification of the scientific theses of the British philosopher. They do not contain any legitimate criticism of Scruton’s essays or any indication of a lack of logic or coherence of argument. It also seems that the British scientist was probably more hurt than the French scholar by the outbursts of his ideological adversaries without any critical analysis of his texts.

The most glaring example of attacks from the left on Raymond Aron was his conflict and the resulting break of his friendship with Jean-Paul Sartre. There is, however, another iconic example for French sociology, although less known outside its borders, of a broken relationship between the author of The Opium of the Intellectuals and his assistant and collaborator Pierre Bourdieu. In November 1959 (some sources mention 1960) the European Sociology Centre in Paris (CSE) was founded through Aron’s efforts. In 1961 he put Bourdieu in charge of the CSE as secretary. The future sociologist, known for his concept of the reproduction of elites, wanted from the very beginning to break with the tradition of sociology practised by such great researchers as Gurvitch, Le Bras, Friedmann, Stoetzel, and Aron himself. They were later called the mandarins of sociology. In 1968 the relationship between the former master and pupil was violently and brutally broken (Comment devenir sociologue. Souvenirs d’un vieux mandarin 167). Raymond Aron made a mistake and, when publishing in Le Figaro a proclamation to scientists and students in which he asked them to write to him in defence of academic tradition, gave the CSE headquarters as his correspondence address. This was met with a negative reaction from other employees. Pierre Bourdieu was just waiting for the opportunity (102) to cut himself off from his older colleague and move to the left (Excellence sociologique et « vocation d’hétérodoxie : 4). He took advantage of this minor incident, as all contemporaries point out. Consequently, Raymond Aron set up the Centre Européen de Sociologie Historique. In 1969 Pierre Bourdieu created the Centre de sociologie de l’éducation et de la culture. As Mendras goes on to state (honestly including himself in this group), Bourdieu and a few other post-1969 sociologists became the new mandarins of sociology at the age of forty or forty-five. Gurvitch died, Le Bras and Friedmann retired, Stoetzel lost influence, and Aron became discouraged about French sociology or, to be precise, sociologists. French historians of sociology regard the break of Aron and Bourdieu’s relationship as the most important caesura separating “old” from “new” French sociology. Many years later, the closest collaborator of France’s most famous sociologist at present, Jeannine Verdès-Leroux, would cut herself off from her teacher. Moreover, in her 1998 book Le Savant et la politique (which is a deliberate reference to the French edition of Max Weber’s Le savant et la politique, a French translation of two texts by the German sociologist, Wissenschaft als Beruf and Politik als Beruf), she severely criticized the academic output of Pierre Bourdieu, considering all his sociology to be merely an ideological discourse (Le Savant et la politique. Essai sur le terrorizm sociologique de Pierre Bourdieu 203). And yet it is possible to move to opposite ideological positions while remaining friends. For example, the sociologist of the next generation, Alain Touraine, remained a friend of Aron’s despite the fact that at the turn of 1970s and 1980s in a visible way (he wanted; note by MG) to act as a left-wing commentator on political events, and he did so in his own way (Widz i uczestnik 302).

Scruton clearly identified himself with the British and European right. As usual, Aron was less explicit. Obviously, he criticized communism and socialism, voted for the representatives of the right side of the French political scene, but at the same time he could be biting also to the right.

So, if one were to label an intellectual’s position by who they vote for, I am a right-wing intellectual, a bit weird, because undisciplined and often at odds with the politicians that I supported in the election. I criticize the politician that I have voted for with a freedom equal to that with which I would attack that politician’s antagonist if elected (304).

Aron could afford to be so impudent, after all.

Raymond Aron (1905-1983) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) – ambivalence.

Roger Scruton – a cure for “Nausea”.

Raymond Aron did not manage to avoid a fondness for Sartre, a feeling legendary for French intellectuals. Jean-François Sirinelli refers to both Aron and Sartre as clerks and overlooks the fact that only one of them (Aron) did not betray the values attributed by Julien Benda (Zdrada klerków) to the intellectual elite (Sartre et Aron, deux intellectuels dans le siècle: 155). Aron often spoke of Sartre warmly, emphasizing his intelligence. Yet they had already had a disagreement in 1947 and broke off their friendship a year later, by no means on Aron’s initiative. It was Sartre who, led by his conviction about the historical necessity of fighting the bourgeoisie and capitalism, broke up old friendships with, for example, Camus or Merleau-Ponty. He was the most brutal towards Aron. In retrospect, Aron recalled with amusement (although I do not suppose that he was laughing during the riots in the streets of Paris in May 1968) that the communist Sartre, who had already managed to sign a petition expressing solidarity with the student movement (Intellectuels et passions françaises: 377), wrote in his vile article “The King is Naked”: It is necessary for all France to see that de Gaulle is naked so that all the students can see the naked Aron. (...) He will not be given his clothes back until he approves of the contestation (Widz i uczestnik: 254). What is shocking even today, the author of Being and Nothingness was not speaking figuratively. He called for the lynching of a 63-year-old man. He made Aron seem like an opportunist sold out to the authorities and denied him the right to a professorial title. I will eat my hat if Raymond Aron has ever contested. And therefore, in my opinion he is not worthy of the name of professor (253). This was a lie, anyway, because Aron criticized the actions of the authorities even if the authorities were ideologically close to him. And yet the French sociologist always spoke of his little companion (le petit camarade) with great dignity. He emphasized: Well, to lose a friend is to lose a part of yourself (167).

This in no way prevented him from ridiculing as to the substance a man lost in a fog of hatred for everything that the West represented. When in June 1953, after the execution of the Rosenbergs, Sartre described in “Libération” the United States as a furious country, the cradle of a new fascism, whose leaders have carried out a ritual murder (i.e. execution after a final and non-appealable court judgment; note by MG) in the majesty of the law, Aron did not hesitate to draw a poignant conclusion:

Although written after Stalin’s death, this text belongs to hyper-Stalinist literature. Nothing is missing from it, not even ritual crime. In Sartrean demagoguery, Americans occupy the place that in Nazi demagoguery was reserved for Jews (Wspomnienia 298).

The quote depicts a feature shared by Scruton and Aron. Both were able – in their different ways – to fight their opponents in their own ideological field. For example, Sartre’s criticism of the USA was based on equating the system of liberal democracy in the United States with Nazism, showing the apparatus of justice as a coercive element of totalitarian power. All this happened in the spirit of the Marxist class struggle. It has always been a favourite technique to corner the interlocutors and force them to prove the obvious. The French sociologist and commentator, with his innate virtuosity, turned the argument around and proved that leftist/Stalinist demagoguery (not Leftism per se) has exactly the same characteristics as rightist/Nazi demagoguery. Aron made use of his Jewish background here. In The Committed Observer he accurately criticizes his ex-friend by summarizing his book, Anti-Semite and Jew:

This is a beautiful book, except that Sartre is not Jewish. He imagines that all Jews resemble his colleague, Raymond Aron, that they have all broken with Judaism, are arch-French, know almost no Jewish tradition, and are Jews only because others define them as such. Sartre’s text ignores quite the real situation of the Jews, authentic Jews (Widz i uczestnik 101)

The theme of Poland and Hungary present in Aron’s comments should be recalled at this point. Knowing the history of the defeat of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 17th century in the war with the Tsardom of Russia and the dependence of the country on the Vistula River on its “brother” in the East, as well as the decisive Russian intervention during the anti-Habsburg uprising in Hungary in 1848-1849, the French intellectual asked a single but fundamental question. It moved the elites of the countries behind the Iron Curtain while exposing the true face of Moscow. It sounded very simple: Is the Soviet Union’s foreign policy Russian or communist? The answer was obvious. Marxist-Leninist internationalism was merely a modern ideological form masking the old imperial Russian Pan-Slavism (Aron et „l’autre Europe: 50).

Similarly, Scruton was able to claim victories on the leftist ground. He began with mocking Dworkin’s apparent leftism (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 47-51), the leftist search for a successor to the bourgeoisie as the enemy of progress, hence the weaker proletarian, the Other spelled with a capital O, the contemporary representative of the precariat, and ended with a dissection of Michel Foucault. Let us stop at this point. Undoubtedly, today, in the bosom of western civilization (not excluding Poland), there is still the question whether it is the left or the right wing that seeks to undermine the principles of a liberal, democratic state of law. Scruton’s exegesis of left-wing guru Foucault’s concepts dissects his concept of the state. Following in the footsteps of Plato in expelling poets from the ideal polis, Foucault postulated the expulsion of judges and all forms of jurisprudence as an element of oppression and their replacement with the justice of the proletariat (68). And this is logical. After all, the entire body of work based on Judeo-Christian tradition, ancient classics and Roman law is nothing more than a Marxist superstructure for the oppression of the exploited class. Just like the French Revolution, in Foucault’s opinion, was directed against judicial institutions, the modern revolution must remove the old system of justice. This is how Scruton summarizes the revolutionary utopia:

Revolution, he assures us, ‘can exist only by radically removing the judicial apparatus, and anything that could reintroduce the penal apparatus, anything that could reintroduce its ideology and enable that ideology to slip insidiously back into common practice – must be banished’ (67-68).

While Raymond Aron had ambivalent feelings about Sartre, Scruton proved without qualms that indeed intellectually the king was naked. The British conservative has always been a vaccine for Sartrianism.

And this should be recalled. Roger Scruton’s critic Stuart Hall in “The Guardian” described the tone of Thinkers of the New Left as bad-faith polemic. It is a concept invented by Sartre in his book Being and Nothingness. According to its creator, bad faith is the adoption of some morality, religion, or social role not as a result of genuine conviction, but in order to define oneself in relation to the social environment through which one defines or objectivizes one’s existence. Bad faith or conformist behaviour of the petty bourgeois good citizens, whose greatest crime is Pharisaism, justifies the passionate contempt that the protagonist of the novel Nausea, Antoine Roquentin, shows for the repulsive world, a nauseating existence that forces him to make constant choices. In a nutshell, the hideousness of the world justifies every act as long as it is a rebellion against the slimy slime of existence. Aron calls the concept of bad faith a ploy to save Sartre’s face, since he denied the existence of unconscious mental facts (Widz i uczestnik 38).

Scruton begins sneeringly with praise for Sartre. It is the kind of admiration that only satanic beauty can evoke, seducing with the allure of words, but leading to the depths of the hell of nihilistic nothingness. Sartre’s prose is both enchanting and metaphysical (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 239). While the narrative of Nausea may even be appealing, Roger Scruton cuts through the illusions of grandeur of this work with surgical precision and reveals the emptiness of this particular quasi-intellectual proposal for humanity. Roquentin burns with disgust at the material world of things around him. He feels nauseous at the sight of people betraying their own freedom in the name of religion or material goods. He is above that. His answer to the slime of existence is proud abnegation. Scruton concludes briefly: A real writer would see Roquentin for what he is: a pompous youngster who flatters himself that his emptiness is sacred (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 240). A conservative philosopher and writer, he sees in the protagonist a resemblance to Sartre, with his smallness and greatest flaw: boundless hubris. It pushes the French existentialist to consider his unbelief in God a substitute for salvation, understood as liberation from the shackles of social norms. Ultimately, Scruton reduces existentialism to mere neo-Marxism.

These are the reasons for disgust, the first object of which is the decay of the world. The world becomes slime – a fango original of Othello Boit. “Being and Nothingness” ends with an extensive description of this slime (le visqueux). Sartre evokes here a vision of the queen of nightmares that arises from the core of nothingness and confronts us with the ultimate negation. Slime is the melting of objects, “damp and feminine suction”, something that “lives in the dark beneath my fingers” and that “feels like intoxication”. This slime “attracts me to itself as the bottom of a precipice might attract” (242).

Interestingly, feminists are silent on this description.

Further in the text, the British philosopher quotes Sartre’s sexual comparison of the necessity of physicality to the desire of the lover, to sadism, masochism, being reefs against which desire can sink. The description of sexual excitement is, in a nutshell, supposed to arouse in the reader disgust with matter and corporeality, reducing human existence to some form of sliminess (by the way, it is worth mentioning that Sartre has been identified in mass culture with the adjective sticky (le visqueux) to such an extent – in the Polish translation of Scruton it has been translated as śluzowaty – that the French dictionary Le Robert pour tous quotes the author of Being and Nothingness as the best illustration of this word). The British conservative sees in this description a genuine fear of existence and at the same time a paradigm of phenomenology. For Sartre there is no salvation, nor love, nor friendship; all relations with others are poisoned by the existence of the body, (...) (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy: 245). These descriptions of the “slimy” side of our existence are meant to convey a metaphysical nausea in respect of everything that exists or has been created for believers. And perhaps Roger Scruton would have been enamoured with the prose and philosophy of the French existentialist, had it not been for the fact that he had been reading the works of Saint Augustine and, by his own admission, the church doctor’s suggestions for dilemmas defined in this way are simply better. Augustine of Hippo’s sense of disgust with the temporal world stemmed from a sense of original sin. Our freedom, which makes us similar to the Creator in the Christian doctrine, is enclosed in carnality. The most humane of the saints wrote that our sexuality best makes us aware of how the body rebels against reason which becomes sickeningly submissive to desire. When synthesizing the content of The Face of God, Scruton writes: It is in the act of conception that we feel our mortality, it is when our consciousness is most unashamedly presented with the slimy, decay-prone nature of our body (246). A comparison of the description of the grossness of the material and liquid nature of the human body by Saint Augustine and Sartre bluntly deals the latter a blow. Something that was supposed to be creative is essentially derivative. There is nothing more humiliating for the author of Being and Nothingness than to be reduced to the role of an atheistic eremite, ...who thunders against the pleasures of this world, but at the same time is not entirely sure that he has already renounced them (246). Scruton, like Saint Augustine, finds comfort in faith. Sartre is modern. He is aware after reading Nietzsche that God is dead. He falls into the trap of addiction to ideology. In fact, he is more pathetic than a follower of any religion who is a believer not out of their heart’s desire but as part of their Pascal’s wager. Jean-Paul Sartre, rejecting the disgusting world imposed on him, built for himself his own private altar, in the centre of which he placed ...the self among the disorder of images of his own, empty illusions (246). Whoever has read and understood Scruton, whenever they think of Sartre, they will smile indulgently and recall the pathetic hermit who, disgusted with existence, decided to retire to an atheist’s retreat – the cafés of Paris.

Raymond Aron – “conservative liberal” and Roger Scruton – “new conservative”

It is not the age difference in the case of these two intellectuals – I understand this concept entirely differently from the definition of intellectuals proposed by Paul Johnson (Intelektualiści) – that seems to be the most significant divergence. Although, from today’s perspective, this may seem surprising, Raymond Aron always considered himself a liberal. Yet, for the leftist French intelligentsia he was still too conservative, hence he was so often referred to as a conservative. The sociologist did not feel strong enough to deny this (Widz i uczestnik: 246). He placed himself in the role of a defender of liberal values such as individual freedom, economic freedom or acceptance of property inequality with absolute emphasis on equality before the law. This was enough to label his approach as “reactive” and, as a left-wing weekly put it in 1978 in a printed interview with him: Raymond Aron is not one of us (Widz i uczestnik: 8). He was attacked all the more brutally because he was considered a traitor to leftist values (Le siecle des intellectuels: 546), as in his youth he had been friends with many people with a heart on the left. French leftist intellectuals failed to recognize that a commentator / intellectual whom they described as anti-leftist is sometimes in the same sense anti-rightist, for example in his analysis of the French presence in Algeria (Une histoire politique des intellectuels: 418). Of course, it must be remembered that in the French tradition since the Dreyfus affair, following in the footsteps of Maurice Berrès, the extreme right on the Seine River had used the term “intellectual” contemptuously, identifying it with the left. This, however, does not explain the furious attacks on Aron, commonly associated with the right wing (Kontrrewolucyjne paradoksy. Wizje świata francuskich antagonistów Wielkiej Rewolucji 1789-1815: 9), thoughtful in his comments and liberal. Yet, it was Sartre, blind to the doctrinal subtleties, who began the shoving of traditional, non-leftist liberals into conservative positions.

Moreover, the left and the right (in the 20th-century France) shared a vision of an intellectual as someone who seeks truth in abstractions, feels distaste for the ambiguities and realities of public life, and is fascinated by the exotic, the aesthetic, and the absolute. (...) The left and the right could not imagine an intellectual attached to the messiness and compromises of liberalism or defending the individual and individual rights for their own sake. From the point of view of Sartre, for whom pluralism was a source of alienation, a problem rather than a solution, this was absurd and could only characterize the physical workers, the farmhands of the dominant ideology. And in that case the person was not a liberal but a conservative, a reactionary. Or more accurately, the person was a conservative precisely because he or she was a liberal (Historia niedokończona. Francuscy intelektualiści 1944-1956: 245).

This should be stressed. Tony Judt reasonably believes that Aron became a conservative not despite being a liberal, but he became one precisely because he was a liberal, that is, he was neither a socialist nor a communist. In such a France, with such right and left, the liberal Aron became a conservative. After all, being a conservative like Scruton in Voltaire’s homeland was and still seems to be unthinkable, or at least truly problematic.

Roger Scruton, after his experiences in 1968, immediately became a conservative. This was not that obvious. A great many American neoliberals had a leftist attitude in their youth. For example, Daniel Bell began as a socialist, remained one in economics, but in politics he moved towards liberalism and in culture even towards conservatism (Kulturowe sprzeczności kapitalizmu: 10). The author of How to Be a Conservative (Jak być konserwatystą) made a peculiar definition of British conservatism by defining it as a politics of custom, compromise and constant indecision resulting from reflection on the consequences of current decisions. For a conservative, a political alliance should look like a friendship: there is no ultimate goal, but changes from day to day according to the unpredictable logic of human relations (Intelektualiści nowej lewicy 17-18). However, treating politics in the same way as friendship is impossible. One has to be pragmatic and be able to choose the lesser of two evils.

For Aron, who was liberal in his views, for example justice was important both for its axiology and for its sociological or economic impact. The economic inequality attacked by all revolutionaries was for Aron not only natural, but morally necessary and just. When wealth inequality disappears, the void is immediately filled by another type of inequality (e.g. inequality of access to goods in a centralized economy), killing economic dynamism. (Opium dla intelektualistów 33). Aron in his sociology of politics (Socjologia polityki Raymonda Arona: 85), the one that he wanted to practise, hence realist (Démocratie et totalitarisme 51), valued healthy egoism, encouraging and motivating the individual to be creative. Inequality is moral because it meets the demands of the community and economic development. Avoiding the trap into which Montesquieu – whom he calls a sociologist (Les étapes de la pensée sociologique 27) – fell, the French commentator omitted the problem which affects many representatives of social sciences, i.e. the recognition that something which causes axiological discomfort (e.g. inequality) turns out to be necessary from the point of view of the development of society. The idealistic approach is a harmful utopia leading to dogmatic science. And yet, debunking myths is the task of the intellectual and the scientist (Opium dla intelektualistów: 10; Inny zapis. „Sekretny dziennik” pisarza jako przedmiot badań socjologicznych. Na przykładzie „Dzienników” Stefana Kisielewskiego 188-189).

Roger Scruton, looking from a conservative perspective, recognized the merits of liberalism in creating space for individual freedom, for deliberative democracy, and for preserving the values of the West. He argued that religion should provide space for dogmatic precepts, and political order is the governance of a community that obeys state laws and rational decisions without recourse to divine injunctions.

Religion is a static phenomenon while politics is dynamic. While religions demand unconditional compliance, the political process proposes participation, discussion and lawmaking based on the consent of those in power. This is how it was in the Western tradition, and it is largely thanks to liberalism that this tradition has persisted in the face of the constant temptation – in its most striking form today among Islamists – to give up the laborious work of compromise and seek refuge in a system of unconditional orders. (Jak być konserwatystą 124-125)

Here the similarity between the French sociologist and the British philosopher can also be seen. Aron saw in liberal philosophy a system of values, the least imperfect foundation for social action, and consequently instructive for political action (Widz i uczestnik 9). Aron’s thinking is based on political pragmatism. Political pragmatism implies the prevalence of freedom over justice in setting priorities, or rather, it is from freedom that the definition of justice as respect for property rights is derived. His liberalism became conservative as soon as he came to terms with human imperfections and human weaknesses – not to submit to them but to subdue them. Even the liberals of Eastern Europe considered it a paradigm that if they wanted to build the state on the foundation of law, their constant concern would be the sense of justice (Pamięć po komunizmie 227). Tony Judt describes Aron’s liberal dilemmas as follows:

Since his student years in Germany, he had been perpetually preoccupied – perhaps even obsessed – with the fragility of liberal politics and the danger of anarchy and despotism. [...] This concern clearly distinguishes him from all other French intellectuals of his generation and explains the extraordinary perspicacity that he showed in the 1930s (...) (Brzemię odpowiedzialności. Blum, Camus, Aron i francuski wiek dwudziesty 198).

Scruton understood traditional liberalism as a doctrine / philosophy that recognizes the right of the individual to choose the types of relationships proposed by society (Jak być konserwatystą: 127). Today, it seems that this liberal postulate is the most tenaciously defended by conservatives. However, Roger Scruton, the British conservative, stipulated that at a certain stage of their development, the liberals thought that a good citizen was obliged to think that everything could be put to a vote, which, after all, leads to the tyranny of the majority. It should be noted at this point that Aron did not agree with all of Hayek’s postulates of neoliberalism. In particular, he strongly challenged on philosophical grounds his liberal concept of freedom (Raymond Aron. La démocratie conflictuelle: 95-99). At the same time, he compared himself to the Austrian-American economist, appreciating his research on logic and epistemology conducted for the scientific discipline that he practised. Aron did likewise with sociology (Leçons sur l’histoire: 212). As Perreau-Saussine wrote, Aron “(...) remains within the noble yet tight confines of liberal traditions” (Raymond Aron et Carl Schmitt lecteurs de Clausewitz). It must be remembered, though, that liberalism is in a sense a self-destructive system that permits self-criticism in the name of proclaimed ideals. For any opponent of liberalism, this is not only an obvious dimension of freedom, but also of justice (W poszukiwaniu sprawiedliwości. Raymond Aron, liberalno-konserwatywny intelektualista: 180). We expect openness and tolerance from liberalism. Therein lies its strength and weakness at the same time.

Raymond Aron saw in liberalism a refuge of European traditions. However, he exhibited a thoroughly conservative caution against falling into the traps of the unknown. Liberalism – for conservative liberalism remains liberalism – represents for the French committed observer a continuation of the ancient, Judaic, and Christian traditions, in their best form, while at the same time rejecting what they carried falsely on the wave of the rapture about the era. Aron could not be fully conservative because he did not reject the legacy of the French Revolution and did not renounce the Enlightenment. As in 1968, he always desired evolutionary reform rather than destruction in a revolutionary frenzy. Conservatism would not have arisen if not for the Enlightenment; it was a counter-revolutionary doctrine and philosophy. Burke’s heirs accepted the development of science, the rise of the state separate from ecclesiastical institutions, the concepts of citizenship, and the remaining attributes of the modern state (Jak być konserwatystą 147). They rejected the absolute negation of the past and tradition.

Conclusion

In the modern world, Raymond Aron and Roger Scruton would certainly be seen by leftist intellectuals as conservative adversaries in the battle for the souls of Europeans. Raymond Aron and Roger Scruton would be made a target for attack. All the more so, as Tony Judt notes, today’s international reality lacks a cool, fact-based and at the same time erudite commentary in the style of Raymond Aron, analyzing the situation in the Middle East, for example. After all, Israelis and Palestinians are destined to be neighbours (Kiedy zmieniają się fakty 138). It can only be added that the current US-China relationship resembles as never after 1945 the situation known as the Thucydides Trap (Destined for war: can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap).

Scruton perfectly recognized the dangers of a one-sided interpretation of reality. When he wrote about the tradition of association, he analyzed it as a manifestation of freedom for all citizens, not just conservatives. Any totalitarianism always begins with the dissolution or licencing of spontaneous and diverse NGOs (Jak być konserwatystą 216). He predicted that the British would want to reject too much interference of the EU institutions with their own country.

What the French liberal and the British conservative unquestionably shared was the view that it was necessary – contrary to the dominant currents of thought – to always uphold the individual freedom of choice and to defend the achievements of past generations by advising rather than imposing solutions to contemporary problems.

Raymond Aron valued the Anglo-Saxon culture. Thinkers from this cultural area considered him the most outstanding French intellectual. The conservative and very English Roger Scruton loved France (Sir Roger Scruton, ce penseur conservateur très anglais qui aimait passionnément la France). And vice versa? Time will tell.

* This article was originally published in the book entitled Tradition and Change. Scruton’s Philosophy and its Meaning for Contemporary Europe, European Conservatives and Reformists, Warszawa 2022.

Works Cited

Aron, Raymond. Leçons sur l’histoire, Editions de Fallois,1989.

- - -Widz i uczestnik, Translated Adam Zagajewski, Czytelnik,1992.

- - -Wspomnienia. Translated by Grażyna Śleszyńska. Sprawy Polityczne, 2006.

- - -La sociologie allemande contemporaine, Quadrige/PUF, 2007.

- - -Démocratie et totalitarisme, Gallimard, 2010.

- - -Opium dla intelektualistów. Translated by Czesław Miłosz, Muza, 2000.

- - -Les étapes de la pensée sociologique, Gallimard, 2002.

Audier, Serge. Raymond Aron. La démocratie conflictuelle, Éditions Michalon, 2004.

Bell, Daniel. Kulturowe sprzeczności kapitalizmu. Translated by Stefan Amsterdamski, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994.

Benda, Julien. Zdrada klerków. Translated by M. J. Mosakowski, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2014.

Fejtö, François. “Aron et <<l’autre Europe>>”. Commentaire. Volume 8/Numéro 28-29, Raymond Aron 1905-1983, Histoire et politique, edited by Jean Claude Casanova, Commentaire, Julliard, 1985, pp. 49-51.

Gacek, Marcin. W poszukiwaniu sprawiedliwości. Raymond Aron, liberalno-konserwatywny intelektualista, edited by Piotr Kulas and Paweł Śpiewak, Od inteligencji do postinteligencji. Wątpliwa hegemonia. Scholar, 2018, pp. 162-184.

- - - „Socjologia polityki Raymonda Arona". Studia Socjologiczne no 4, 2013, edited by Tomasz Szlendak, Wydawnictwo Instytutu Filozofii i Socjologii PAN, 2013, pp. 85-102.

Graham, Allison. Destined for war: can America and China escape Thucydides’s trap, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

Johnson, Paul.(1988), Intelektualiści, transl. A. Piber, Editions Spotkania, 1988.

Judt, Tony. Kiedy zmieniają się fakty eseje 1995-2010, transl. A. Jankowski, Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, 2015.

- - -Brzemię odpowiedzialności. Blum, Camus, Aron i francuski wiek dwudziesty, Wydawnictwo KRYTYKI POLITYCZNEJ, 2013.

- - -Historia niedokończona. Francuscy intelektualiści 1944-1956, transl. P. Marczewski, Wydawnictwo KRYTYKI POLITYCZNEJ, 2012.

Łęcki, Krzysztof. Inny zapis. „Sekretny dziennik” pisarza jako przedmiot badań socjologicznych. Na przykładzie „Dzienników” Stefana Kisielewskiego. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2012.

Mendras, Henri. Comment devenir sociologue. Souvenirs d’un vieux mandarin, Actes Sud, 1995.

Minc, Alain. Une histoire politique des intellectuels, Grasset, 2010.

Scruton, Roger. Intelektualiści nowej lewicy. Translated by T. Pisarek, Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo, 1999.

- - -Jak być konserwatystą. transl. T. Bieroń, Zysk i S-ka Wydawnictwo, 2016.

Sirinelli, Jean-François. Intellectuels et passions françaises, Gallimard,1990.

- - -Sartre et Aron, deux intellectuels dans le siècle. Hachette Littératures, 1995.

Śpiewak, Paweł. Pamięć po komunizmie. Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, 2005.

Szacki, Jerzy. Kontrrewolucyjne paradoksy. Wizje świata francuskich antagonistów Wielkiej Rewolucji 1789-1815, Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN,2012.

Verdès-Leroux, Jeannine. Le Savant et la politique. Essai sur le terrorizm sociologique de Pierre Bourdieu, Grasset, 1998.

Winock, Michel. Le siecle des intellectuels, Éditions du Seuil, 1999.

Netography

Jolly Marc, « Excellence sociologique et « vocation d’hétérodoxie » : Mai 68 et la rupture Aron-Bourdieu », Revue d’histoire des sciences humaines [En ligne], 26 | 2015, mis en ligne le 07 mars 2019, consulté le 06 décembre 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rhsh/2001 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rhsh.2001 Accessed 10.01.2021

Laine, Mathieu. Sir Roger Scruton, ce penseur conservateur très anglais qui aimait passionnément la France https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/sir-roger-scruton-ce-penseur-conservateur-tres-anglais-qui-aimait-passionnement-la-france-20200113 Accessed 08.02.2022

Perreau-Saussine, Émile. Raymond Aron et Carl Schmitt lecteurs de Clausewitz www.polis.cam.ac.uk/contacts/staff/eperreausaussine/aron_et_schmitt_lecteurs_de_clausewitz.pdf Accessed 19.12.2021

Comments (0)