The Puzzling Architecture of Civilisation

The main theses of the text:

* While we still don’t know how much we don’t know about the world’s social structure, we are increasingly fiddling recklessly with its construction.

* Humanity’s struggle with COVID-19 indicates that civilisation founded on the scientific and technological revolution of the Enlightenment has somehow blinded itself.

* Democratic societies will only begin to deal with the world a little better when they abandon the pernicious dogma: “there are no more communication barriers in the internet age”.

* We have gained the technical capacity for the irreversible destruction of our civilisation before we have even correctly understood its construction.

* Reflecting on the architecture of human civilisation sheds new light on the waves of protests that swept through Poland in October/November 2020.

* If we do not part with certain illusions about the current cognitive situation of humanity, we will not deal with the fundamental threats to civilisation.

* A newly rethought conservatism can be a pathway for charting the course of human causation.

If we (...) were to abandon all hypotheses whose veracity we cannot prove, we would soon return to the level of savages who trust only their instincts[1].

Twitter insights

Let’s start by reading the signals from a radar device called Twitter. The first signal comes from a well-known billionaire. The second is from a prominent analyst of political and cultural processes.

On 14 November 2020, Elon Musk tweeted: “Am getting wildly different results from different labs, but most likely I have a moderate case of covid. My symptoms are that of a minor cold, which is no surprise since a coronavirus is a type of cold”. [2]

We can assume that the billionaire celebrity used neither cheap, uncertified tests nor poor laboratories. But after months of testing for the virus, the technical ability to detect it in the world’s most powerful country remains unsatisfactory.

A day later, Andrew M. Michta, the author of numerous books and political science expertise, notes: “DC feels like a ghost town. I just did some calculations: at 1.5 million #COVID19 related worldwide deaths we are talking about 0.015% of the global population (1918 Spanish flu estimated at between 2.1-6.0% global mortality). What are we doing to ourselves .... And why...?” [3].

Let us take these two entries - one by the co-creator of today’s scientific and technological civilisation, the other by its perceptive analyst - as signs of the times.

On the inefficiencies of US institutions in the fight against the pandemic, much has been blamed on Donald Trump. However, it would be difficult to link his decisions to the quality of diagnostic technology available in California. The low capacity of the diagnostic tools available to technoscience more than six months after the problem was publicised globally cannot be explained by the mistakes of any politician.

Michta, in turn, drew attention to the global dimension of the grossly disproportionate manner in which power structures in many countries of the world and international organisations are responding to the scale of the challenge. Michta is concerned that humanity is playing the wrong game - both with nature and itself. It is hard not to consider the hypothesis that our civilisation, founded on the scientific and technological revolution of the Enlightenment, has somehow blinded itself. Is it at its own request?

One important feature of today’s civilisation is haste. This has led to an increasing abandonment of the culture of perfection by business: many companies deliberately release shortcomings (e.g. in software development) because anyone who pays too much attention to the quality of their products is out of the competitive game. How many nervous announcements have we heard in recent months about a breakthrough in work on the Covid vaccine, and how often has it turned out that there is something wrong here after all....

One of the sillier thoughts

“In the age of the internet, there are no longer any communication barriers” - this is one of the sillier diagnoses of civilisation in recent years. This thought disrupts our understanding of the modern age. Its fallacy has many dimensions, but we will focus on two: the obstacles in the way of gaining actual knowledge and the barrier to getting the message across effectively.

The first barrier encountered by someone who wants to extract useful knowledge from the vast online reservoir of information is the Great Mix-up. The mixing of everything with everything: the important with the unimportant, the serious with the ironic, the true with the deceitful, the sensible with the absurd, the real with the fictional, the good-natured with the malicious, and so on.

That a piece of information looks plausible does not mean it is true. It may be crafted or spontaneously configured in such a way that it appeals to a particular audience. This is, after all, the job of marketers, PR specialists, and spin doctors, not to mention classic propagandists: to act in such a way that the messages appear credible.

When not under time pressure, a well-trained analyst can deal with the obstacle of the information hotchpotch. He knows the typical cognitive traps. He can access valuable sources of information; what he can, he will check himself, and on other issues, he knows who to consult. He will pluck what is edible from the ocean of the Great Mix-up and produce a portion of knowledge that is useful to decision-makers or the wider public, influencing, for example, the direction of health policy in a country. But even an analyst won’t say that there are no communication barriers. It may be more convenient, with less need to move from place to place, to call, to meet, but the numerous barriers to overcome not only exist all the time but have been compounded.

Let’s assume that valuable new knowledge has been generated. But now, the new message has to be brought to the public. At this point, we have the reverse of wading through the Great Mix-up. This Mix-up is, after all, nothing more than a structurally poisoned infosphere. An information bustle in which there is no shortage of distractions: bargains, discounts, erotic luring, teasing with violence, misinformation, spam, trolling... Even if new valuable knowledge has already been created, it does not have to get through the poisoned infosphere. It is not easy for the truth to win in competition with other incentives (including the interests of various groups), e.g. to reach the minds of decision-makers who should act based on new knowledge.

Democratic societies will only begin to deal with the world a little better when they abandon the pernicious dogma that “there are no longer communication barriers in the internet age”. Because the internet has evolved in such a way that it has become one big communication barrier! And when we cannot react rationally in the poisoned infosphere - we react instinctively.

Recently in Poland, we have seen how the infosphere barrier has been broken through. Contributing to its breaking were representatives of the so-called Women’s Strike, an environment that consciously reached for - openly breaking good manners and important cultural taboos - a technique of social mobilisation through public verbals. If the internet had actually brought down barriers to communication between people, would girls and women have had to resort to vulgarity en masse?

Indeed, the Internet has disrupted our ability to understand the world. It has produced a state of already chronic cognitive impairment in humanity. As if this were not enough of a pandemic, societies are additionally succumbing to conspiracy obsessions and hyper-freedom illusions. Unless we part with certain illusions and sheer dogmas about humanity’s current cognitive predicament, we will not meet the challenges of civilisation.

We do not know what we are doing

Why are so many things wrong, not fit together in the human world? To answer this question, we propose a metaphor of the architecture of civilisation.

Let us assume that humanity is moving through time, sailing in a ship whose architecture - the types of building blocks, how the elements are connected - it has read and understands only partially. We fear that it is a smaller part rather than a larger part. This ship is ... human civilisation.

In the long process of history, the ship came into being as a result of our actions, of which, however, only a small part was consciously devised and implemented according to plan. The present civilisation (and every civilisation before it) came about as a result of a tangle of mostly spontaneous processes, only sometimes effectively coordinated by human minds.

Civilisation is a ship in which we sail through rough seas whose maps are only partial - the chaotic reactions to the COVID-19 attack best demonstrate the gaps in this mapping of the world. We know only fragments of the ship’s design, without knowing how much of the design we have yet to learn. Despite this, we cannot resist the temptation to tamper with this ship’s design constantly. We often meddle by trial and error - unable to distinguish when we can afford to do more because we are experimenting only with the structure of the superstructure, e.g. improving the crew accommodation, and when our actions compromise the ship’s navigational system or alter the design of its rudder. Sometimes, in the pursuit of progress, we stop noticing that we have just drilled through sections of the hull below the waterline, doing so without first ensuring that the watertight bulkheads between the relevant sectors have been sealed. In short, we have gained the technical ability to irreversibly destroy a ship (civilisation) before we have even correctly understood its construction.

As Jared Diamond’s analyses [4] brilliantly demonstrate, we have built our civilisation in navigable (geographical) conditions that we did not choose ourselves and still only partially understand. Human actions are subject to genetic and cultural programming, only fragments of which we have so far been able to decipher. The interaction of geographical conditions with this programming means we do not actually know what we are doing. We do not know in at least a double sense: psychological and sociological.

Let us illustrate the point with facts. At the turn of October and November 2020, a wave of protests swept through Poland caused by the Constitutional Court ruling that the right to eugenic abortion was unconstitutional. The large scale of protests took everyone by surprise. What are their motives? Is it possible that the protesters are primarily concerned with the right to abortion? There is no obvious answer to this question.

In psychological terms, we do not know what we are doing because, according to studies of the human mind, most of the actual motives for our actions we not only do not know but are even fundamentally unable to decipher. We are often not in control of the forces that are released in our bodies. If we were to ask, for example, the motives of people who, in solidarity with the protesters, put up posters with a lightning bolt symbol in the windows of their homes, we would receive a variety of answers, including some that do not agree with each other. These protests were undoubtedly some kind of eruption of anger, but every emotion psychologist knows that anger can be a manifestation of so-called displaced aggression, occurring when we cannot direct our anger at the actual perpetrator of our frustrations or when we mask the source of frustration from ourselves.

The sociological dimension of our ignorance is that human actions, especially collective and large-scale actions, almost always have unintended consequences, often unnoticed for a long time. Sociology has been struggling with this issue from its inception, without much success.

But the most important thing is that without fully knowing either why we do something (e.g. when we are in favour of life and against abortion) or what we actually cause (e.g. by supporting a reform movement), we nevertheless transform the construction of human civilisation. In doing so, madmen can initiate changes in the architecture of our ship no less than hyper-rational technocrats (it is worth reading Douglas Murray’s book “The Madness of Crowds. Gender, Race, and Identity” from this angle [5]).

In a word, by acting for reasons we dimly know, we produce effects we often cannot foresee. We recklessly reshape the architecture of a civilisation whose structural bonds still hold many secrets.

Secrets of shipbuilding

That human cultures, built by the spontaneous synchronisation of millions of human actions, are “smarter” than any human, was well understood by Friedrich von Hayek (1899-1992). He was unlucky - the Nobel Prize was awarded to him in 1974 in economics. Because of that, this eminent thinker is usually placed in the ghetto of economic researchers, whereas he also, or perhaps above all, conducted profound studies on culture and the nature of human cognitive processes.

He wrote about the role of tradition as follows: “Tradition is the product of a process of selection from among the irrational or rather »unjustified« beliefs which, without anyone’s knowledge or any deliberate action, contributed to the increase in numbers of those who followed them (not necessarily in connection with the motives, for example religious, for following these traditions). The selection process that formed customs and morals may have taken into account more actual circumstances than individuals could consciously recognise. As a result, the tradition in some respects surpasses the human mind or is »wiser« than it.”[6] (distinction - K., A. Z).

So what do we not know about the architecture of the world we live in? For example, we are not clear what the sources and stabilisers of morality are. We do not know whether, with the more profound disconnection of morality from metaphysical ideas (the process of secularisation), we can resist the “descent” of our behaviour to the animal level.

Nor do we know whether and to what extent one of the necessary conditions for maintaining a certain architecture of civilisation is biodiversity (the chains that bind numerous plant and animal species together).

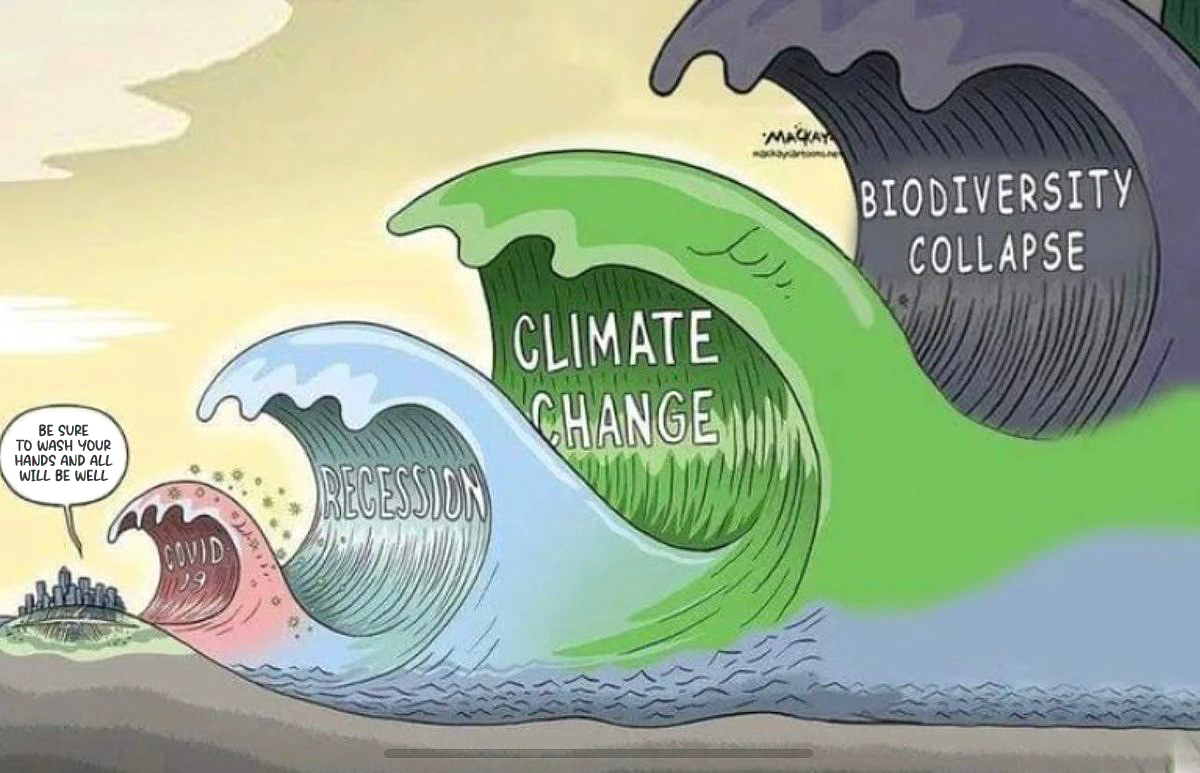

The already memetic figure above shows the natural context of our metaphor of the overlooked dimensions of civilisational architecture, which includes the biological context in which the human world exists. Humanity is simultaneously subject to many mechanisms, only some of which we have come to know.

The eminent American geographer, Jared Diamond, wonders what rate and extent of extinction of species living on our planet might be, so to speak, systemically safe. When will the extinction of species to which human activity contributes first deprive our ship (civilisation) of the ability to obey the rudder, i.e. guide development in the right direction, and when will it cause us to lose buoyancy altogether? This is the kind of problem we can formulate, but we don’t seem to have the tools to solve it. The same applies to a handful of the following issues.

The field of what constitutes human experience has always been divided into predictable and partially controllable events and perceived unpredictability. But can we pinpoint when the range of surprising phenomena (black swans) becomes so broad that civilisation not only temporarily loses stability but even collapses?

And can we determine the developmentally safe level of saturation of the public consciousness with false notions (fake news, disinformation) and absurd notions (information noise)?[7] A level beyond which even a billionaire cannot count on reliable health care.

Can we draw an interval between the resources of the rich and powerful and the wealth that the people have at their disposal, an interval beyond which social dynamics will be out of anyone’s control? And isn’t, for example, China’s social credit system an innovative way to expand this span in a systematically safe manner?

In the dispute between policies of openness and closedness, e.g. in the context of regulating migration flows across national borders, are we able to determine any rational optimum in advance?

Finally, in the technology-driven process of elimination of old professions and emergence of new ones, are we able to recognise the tipping points at which the social costs will exceed our moral resilience?

Human development can be viewed as a process of breaking old taboos and creating new ones. But what happens when there is almost simultaneous destruction of taboos in too many fields? What other social regulators then start to fall apart?

Such questions can be multiplied. Human civilisation has an architecture that allows the ship to be rebuilt as it sails. Human systems have great potential for adaptation. However, it is not limitless. The twilight of civilisation can occur as a result of the accumulation of instabilities in too many different fields simultaneously. An unexpected accumulation of problems of various types can drain the resources needed to activate crisis management procedures.

Two major mistakes

The above argument allows us to consider the question: is Polishness (culture, tradition, history) not smarter than individual, even the most prominent Poles? Let us look again at the protests that erupted after the Constitutional Tribunal verdict was announced.

Bearing in mind that we, the people, often, contrary to our perceptions, do not know what we are doing, we will point out that these protests help us to grasp two serious cognitive errors - and each has significant practical consequences for the lives of Poles.

The first error, sociological, goes to the account of the leadership circles of the “good change” camp ruling Poland. The second error, a civilisational one, is committed by the leaders and ideologists of the “progress” camp - one can point here to the circles of “Gazeta Wyborcza”, “Krytyka Polityczna”, and “Kultura Liberalna” and related circles. Both mistakes - despite their different scale - are of a serious calibre.

The crux of the sociological error is the loss of contact with the actual social moods, fears and hopes by the leaders of the “good change”, especially with the mentality of young Polish women. The reasons for this can be interpreted as follows: the weakness of the political opposition to the “good change” (what was overlooked here was the strength of the wave of support that Rafał Trzaskowski’s candidacy for President of the Republic of Poland was able to arouse), the inability of the opposition to formulate a programme that resonates with the broad social sentiment, its divisiveness and its intellectual deficits, which are visible to the naked eye, the United Right’s winning of a whole series of democratic elections, triggered a tendency towards triumphalist thinking. In the more ideologically fundamentalist part of the “good change” camp, this apparently led to the belief that there was a more resounding social consensus for deepening some form of conservative revolution. Meanwhile, the scale of two interconnected, albeit non-obvious, processes was overlooked: the hyper-individualisation of the mentality of youth immersed in the world of digital stimuli and the scale of the crisis of the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church in Poland. And without a real, and not merely declared in religion lessons, rooting of religiousness in everyday social life, especially of the young generation, the conservative revolution in morals cannot succeed.

The dulled social hearing of the “good change” has caused it to overlook the scale and dynamics of a parallel world existing somewhere next door, including the reality of the young generation of emancipating, “modern” women. It failed to recognise that newly arrived hyper-individualistic consumers - certainly more consumers than fellow citizens - could become a political powder keg under pandemic stress.

In addition, the coronavirus pandemic proved to be a severe stress test for the institutions of the state. It was the state that, through the contested CT ruling, raised moral standards towards the young (not, after all, towards pensioners voting for the “good change”) but failed to provide beforehand an efficient network of support institutions for families of disabled people in advance.

As a result of the change in the rules of the game in everyday life brought about by the necessary moves by the authorities to combat the pandemic, exasperated, stressed, panicked Poles - rushed to a “civic” uprising. However, this newly aroused collective subjectivity is one-sided: the young demand rights, almost completely disregarding their obligations to the community. This predominance of rights over obligations is a fragment of a broader civilisational architecture, through the prism of which it is worth considering the situation in Poland.

The TK ruling was a movement that can be justified in terms of morality and civilisation, but sociologically (e.g. logistically) unprepared. Why do we consider it a civilisationally justifiable move?

For a number of years - some date it back to the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 - it has been quite widely acknowledged that liberal democracy is in crisis; it is not uncommon even to speak of its twilight. The crisis is recognised by both critics and supporters of liberal democracy.

Regardless of the fact that the slogans and articulated motives of the demonstrators are very diverse, that they are the result of an accumulation of rational fears and irrational fears, the key motive (and indeed the fuse) of the demonstrators is the widely understood right to abortion. One can look at it as Prof. Antoni Dudek did, saying that in Poland these days, the moral revolution previously carried out in the affluent West is being completed, that there is a “catching up” taking place, which Poland has on the way to liberalising social relations.

Many Poles demand that we emulate the institutional solutions of liberal democracy, a systemic and cultural formation whose crisis has already been widely proclaimed (although still poorly diagnosed).

In the pursuit of modernity and freedom, the young generation, though not only it, is demanding that Poland join a systemic form that has already lost its vitality in the old West. When liberal democracy has begun to reflect on its shortcomings, slowly realising that hyperpluralism, hyperfreedom and hyperindividualism are like nooses around the neck of the free world, our national progressives are fiercely courting these hypertrends in the dark.

Back to Diamond: “Like other animal populations suddenly out of control of their previous limits to growth, we too risk destroying our resource base - destroying ourselves”[8]. According to Diamond, “self-destructive abuse of the environment, far from being a modern invention, has long been a major driver of human history” [9]. Diamond focuses attention on the issue of human-induced extinction of species to which we are - often without being very aware of it - linked by numerous chains of addiction. We propose to direct attention to a resource of a different kind: morality.

Morality is a resource that reduces the cost of social control - in line with the adage that when someone has the basic norms of social life encoded in their mind, there is no need to put a policeman next to them. Today, the proliferation of automated, electronic surveillance systems offers the illusory hope that, lo and behold, there is no longer any need to work on human spirituality. After all, Silicon Valley’s billionaire cyber masters will digitally “take care” of the stable social order, replacing policemen with algorithmically controlled post-policemen, such as YouTube tempters.

In the meantime, it may be that the destruction of moral resources accelerates the reckless destruction of biosphere resources. That it is now at the interface between moral practices and strategies for legitimising such and not other policies towards nature that the sensitive dimension of civilisational architecture is hidden [10].

Conservatism once again

Brain researcher Michał Fortuna tweets: "Whenever there are new solutions and technologies, there will be the talk of »the possibility of crossing a certain boundary, a certain Rubicon«, a boundary that no one can define because it is fluid.” [11]. He is right. We can’t define these kinds of boundaries. But the fact that they are historically fluid does not mean that crossing them can go unpunished. This is why our argument leads us to postulate a legitimation and a rethinking of the project of republican conservatism [12].

We postulate a reflection directed in a significantly different direction from the thinking recently promoted by the weekly magazine “Polityka” within the framework of Olga Tokarczuk’s Ex-centre project [13], which is to become a platform for an extra-routine, eccentric diagnosis of the state of the world.

In our view, the world is already excessively eccentric. There are already too many centrifugal forces that have been able to achieve sizable ranges of subjectivity beyond their proper traditional domains of interest and influence. And these include lobbyists, start-ups, bloggers, YouTubers, influencers, large law firms, consulting companies, investment banks, online platforms, media conglomerates, social movements, political parties, genderists, secret services, internet trolls, hackers, and finally, more or less disorganised or outright degenerate states. Doesn’t every second developer of a new, sensational application count on becoming an influential figure in addition to monetising their product? In the current context, we consider the demand to further develop “eccentric” thinking to be harmful.

It is not hard to associate things super eccentrically. Human history is not short of original figures’ eccentric approaches to the world. Aren’t the examples of horrors that have afflicted humanity nothing more than eccentric approaches to the challenge of happiness? What if fascism were improved by eccentricity? Better to work decently on the old conservatism. And it needs to be worked on because with the fanatics of progress - those whom Jordan Peterson says are ideologically possessed [14] - the conservatism is not coping.

We need a fresh iteration of conservatism, a dusting off of the old moral scaffolding that has undergone various tests of endurance throughout human history. We need an overhaul of those institutions that are the mainstay of the social order and not just generate ideas of permanently reinterpreting and redefining everything.

What are “human rights” supposed to be today, how is freedom to be distinguished from the chaos brought by freedom without borders? It is in this context that one should ask: “What is the point of people having the right to elect their representatives if they can do less and less?” [15].

Can the disappearing subjectivity of the representatives of the democratic will be rebuilt without the revival of some formula of the nation-state? This is another dimension of conservatism that should be directed centrally - namely towards human solidarity. And can this solidarity leave out unborn human beings? And concern for future generations (preserving the planet’s resources for them)? And concern for the good name of our ancestors?

[1] Friedrich von Hayek, Zgubna pycha rozumu, Kraków 2004, p.106

[2] https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1327743762273955841; accessed on 18 November 2020.

[3] 15 November 2020; https://twitter.com/andrewmichta/status/1328092426377056263; read on 17.11.20.

[4] See esp. Trzeci szympans. Ewolucja i przyszłość zwierzęcia zwanego człowiekiem, Kraków 2019.

[5] Poznań 2020.

[6] F. Hayek, op.cit., p. 117.

[7] See H. Frankfurt, O wciskaniu kitu, Łódź 2020.

[8] Diamond, op.cit., p. 462.

[9] Ibidem, p. 463.

[10] Such an "architectural" metaphor was recently used, for example, by Tomasz Sawczuk from „Kultura Liberalna”; https://kulturaliberalna.pl/2020/11/16/sawczuk-w-poniedzialek-czym-jest-wolnosc-i-czy-panstwo-zabiera-nam-pieniadze/; read on 20.11.20.

[11] https://twitter.com/M_G_Fortuna/status/1327597838885380097; read on 18.11.20; punctuation corrected.

[12] We have indicated another direction of this validation in our text „Okiełznać zmianę. Bezpieczeństwo ontologiczne, rozwój technologiczny a kryzys Zachodu” [Tame the change. Ontological security, technological development, and the crisis of the West], Filo-Sofija, nr 36, 2017/1; accessed at: http://www.filo-sofija.pl/index.php/czasopismo/article/viewFile/1095/1068; read on 05.11.20.

[13] The series of essays of the project begins with Olga Tokarczuk with a text „Człowiek na krańcach świata” („Polityka”, 40/2020).

[14] https://fee.org/articles/the-diagnosis-and-treatment-of-ideological-possession/; accessed on 14.11.20.

[15] B. Wildstein, „Polska na mapie kulturowej wojny” [Poland on the cultural map of war], „Sieci”, 9–15.11.20, p. 69.

The text originally appeared in the monthly magazine "Wszystko co Najważniejsze".

Read also

The problematic nature of the digital age

In the fourth episode of 'The Essence of Things', we discuss the nature of technological development and the consequences of the digital revolution. Our guest is Professor Andrzej Zybertowicz - sociologist, analyst, political consultant, advisor to President of Poland - Andrzej Duda.

Comments (0)