In the 1990s there was a type of vulgar complacency in the social sciences. This was ushered in by the after effects of the Cold War which, it was presumed, meant the 'end of' something or other. The 'end of ideology', the 'end of history'; a supposition that the damaging 'ideologies' of the twentieth century were exposed and dismantled.

Yet what this congratulatory premise failed to note was that 'Liberalism' (as an ideology) was prone to the exact same Philosopher's stone. This stone is the stone of 'Sisyphus' - in that ideologies merely 'reincarnate' themselves, through language, and become hybrids of a previous ideology. They continue to act like Sisyphus - pushing and pushing the stone up to the top of the hill again and again. Hence Marxism reproduces itself in varieties of liberalism. Having failed completely, it divorces its elements, reshuffles, and abandons its premise of surplus value or the alienated worker and pushes the stone of race and gender. However, it is still an 'ideology' of sorts, and it underwrites the ontology of the occident.

The contention I put forward here is that liberalism is as debilitating an ideology as was communism or fascism. In what Zizek describes as the 'master signifiers' for Ideologies[1] - these are the seminal words which define the perceptions of individuals. The reality does not matter. Therefore, ideas such as 'we live in a democracy', 'the rule of law', 'human rights' are, just as pertinently, similar in essence to such things as 'God', 'Progress' or the 'Nation'. It matters little the reality - if these core attitudes can be fostered then 'aberrations', 'exceptions' can be tolerated. Zizek calls these core beliefs the 'Sublime Objects of Ideology'. These are the axiomatic values inherent in regimes. Ostensibly all ideologies are self replicating and the elite manipulation of irrational sentiment. The Chinese may, therefore, promote a foreign policy of 'Tianxia' (all under heaven) as a cosmopolitan benevolent outreach to the Orient, but the core is one of aggressive influence and resource orientation.

Ideologies start out as variations on Plato's forms. So, they construct a system 'a priori' i.e., the Enlightenment vision of reason for Liberalism. Then fill in the details. The result in the case of liberalism is top heavy with Scientism, Law based on a categorical imperative, a universality of global culture etc. Communism starts out with a vision of egalitarianism; Fascism as the elevation of 'the state' and 'the nation'. The key weakness of all 'ideologies' is their assertion of 'a priori' truths. As Hegel opined 'The Owl of Minerva only takes flight in the dusk'. In that the awareness of history and philosophy is only grasped after the fact, when the owl has flown.

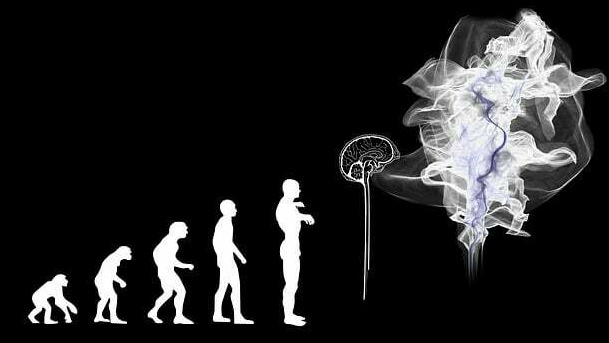

What is transpiring in the Occident is that the contradictions of Liberalism are 'showing' themselves. Yet there are those, despite the evidence, who keep on pushing the stone. Take, for example, the American philosopher Francis Fukuyama. Fukuyama described the modern era, and particularly the globalisation of the 1990s as the 'end of history'. This was the culmination of a long process of what Hegel described as the 'consciousness of freedom'. In this dialectic there is a move through meaningful history, from say, the early civilisations of India, China and Persia, to Ancient Greece, the Roman Empire and so on. This type of history was taken up by Christianity (the realisation of the Creator's idea) and later, Marxism. The world is the evolution of a sense of purpose and reason.

Augusto Del Noce saw in this periodisation of history a belief in the 'transcendence' of history into the rationally perfect immanent end-world. For Del Noce this belief saw the rational trajectory as culminating in atheism and nihilism. Even Marxism has abandoned its messianic quest for variations on managerialism and materialism. Consequently, rather than usurping the exchange value of commodification (the basis of people's supposed relationship to each other) Marxism realises itself in the affluent society and the same correspondence.

The problem with the aforementioned periodisation of history is that it came to a standstill in 1945. The immanentism of this flowing history was ruptured, so liberal interpretations go, by Fascism and Communism, which were aberrations, forms of civilisational collapse. What Del Noce puts forward, and I reiterate in my book 'Nowhere Fast: Democracy and Identity in the Twenty First Century'[2] is that the secularised world of the twentieth century contains all materialist forms: Fascism, Communism and Liberalism. The kernel of their thought is a rejection of any metaphysical aspect. The final outcome of historical progress for the liberal mind becomes scientism. It is not therefore a reactionary case for the value of tradition. It is more a case for remaking rationalism with spaces for metaphysics.

What are the implications of this thesis for freedom? The modernist sublime objects of ideology are therefore posited in a scientific logic which valorises materialism and sees 'authority' as repressive. Hence the dialectic has not reached a liberal utopia of rational thought. The new dialectic is one of reason sublimated to a basic gorging on instincts, the end game of materialism and the market. The ideology it presupposes therefore, which is enacted within liberal democracies, is the political notion of the 'abolition of controls'. These controls can be notionally 'external' (i.e., positive law) or internal (freedom as an extension of Mill's 'harm principle'). Hegel had anticipated this contradiction when he abhorred this 'negative freedom'. Authority, on classical Greek lines, is the source, not the antithesis of freedom. However, Hegel maintained that authority must be grounded in tradition and community, not abstract rules. This means a return to a participatory 'polis' and what Patocka termed the 'care for the soul'.

The legacy of this misinterpretation of Hegelian development is a unidirectional view of history as inevitable 'progress'. A philosophy of unrestrained nihilism and atomism (although necessary for the neoliberal market) has resulted in a collapse of consciousness where freedom is seen in a narrow conduit of negative freedom (vis a vis Isaiah Berlin[3]) exhibited in social dislocation and collapsing communities.

The 'Fukuyama Syndrome' is that, despite observing such manifest trends, this Ptolemaic tendency figures predominantly in the public intelligentsia, think tanks and Universities. However, far more dangerous is the myopic outlook translated into foreign affairs. In April 2022, Fukuyama reiterated his prophecy that 'Ukraine will win' and 'the Ukrainians will succeed in driving the Russians out of their territories'[4]. Fukuyama sees the real cause of the Ukraine conflict as, not one about the expansion of NATO, but Russia's fear of 'democracy'. Then in October 2023 Fukuyama met with members of the Stanford Freeman Spogli Institute in Kiev. He noted that 'People were going to restaurants and nightclubs and driving around. Apart from the burned Russian tanks on display and soldiers everywhere, you wouldn't necessarily know that it's a nation at war'. Boris Johnson, Timothy Snyder, Niall Ferguson, despite war raging above their heads, met in a luxury conference room called 'YES WAR ROOM', and after spent hours dining in sumptuous surroundings, like Napoleon and Alexander, on that raft in 1807 at Tilsit. Yet the 'funeral baked meats did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables'.

Fukuyama, surely the 'Ostrich of Minerva', stated that:

'The 2024 presidential election in the U.S. is going to be one of the most important elections in our history. World history could go in very, very different directions depending on the way it goes...'. I was under the impression we had reached liberal utopia. Now we are told 'any direction'. Alas the Hegelian feathers are no more. Francis Fukuyama, not one for admitting the error of prophecy, instead digs down deeper, in those affluent think tanks of liberalism, pushing the neo-liberal stone, this time, not of globalisation, but of globalised war. Perhaps, therefore Schopenhauer was correct, in observing that 'Governments make of philosophy the means of serving their state interests, and scholars make of it a trade'[5].

Hegel was correct in thinking that concepts of freedom are more than having free reign to do as one pleases. In his 'Philosophy of Right' he places the phenomenology of experience in an already given world of needs and desires. These formations come before action; they are formed by millenia acting out of community. Kant's solution, previously, had been to apply a kind of universal categorical imperative to control the elements of desire. Freedom is the obeying of reason, eliminating desire. To act as if we were observing a universal law. The problem with ideas of Universality is that they apply the same rules for different cultures. They do not allow for the vagaries of communities. Hence there is a huge mismatch between liberal universal reason and the peculiarity of culture. Hence Hegel would also maintain that, due to biological instincts on the one hand and constraints of community and tradition, there is a limited scope for free will. Notions of 'negative liberty', the leitmotif of liberal democracy, is pure fiction. A more nuanced idea of freedom was extended later by the likes of Heidegger, Wittgenstein and Sartre's infamous 'we are condemned to be free.' Freedom, therefore is 'constrained' by a particular epoch or community. That is why the historical evolution of history cannot evolve to a 'particular' conclusion, such as Fukuyama's liberal democratic state, because all periods are subject to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, as Shakespeare said. Indeed, the opposite of Fukuyama's dream is that of the pessimism, the nihilism of Macbeth. To avoid nihilism, to escape from prophetic history and ideologies like the 'end of history' it is necessary to see that freedom is authority and that identity is constructed through community and cooperation. We are not 'condemned to be free' but free to be condemned.

[1] Žižek, S. (2009). The sublime object of ideology. Verso.

[2] Bolger, B. P. (2023). Nowhere Fast: Democracy and Identity in the Twenty First Century. Ethics International Press.

[3] Berlin, I. (1958). Two concepts of Liberty. Clarendon Press.

[4] https://www.americanpurpose.com/blog/fukuyama/why-ukraine-will-win/

[5] Scruton, R. (1997). German philosophers. Oxford University Press.

Read also

The End of Globalisation

There seemed to be an inevitability in the talk of globalisation and the 'end of history' which ushered in the twenty first century.

Brian Patrick Bolger

Even the Poets are Killing: Fico and the New Iron Curtain

The Slovak 'Lee Harvey Oswald' was a 71 year old poet. It's what poets do these days. No waltzing around daffodils in the Lake District or smoking Opium a la Coleridge.

Brian Patrick Bolger

Charles III and the Coronation: 'Government of Himself'.

It was TS Eliot who remarked that 'When a term has become so universally sanctified as 'democracy' now is, I begin to wonder whether it means anything, in meaning too many things'.

Brian Patrick Bolger

AI - 2023: The Ghost in the Machine is Out

If we were to ask one dominating question about the Artificial Intelligence debate then it should be this one: What makes human beings special?

Comments (0)