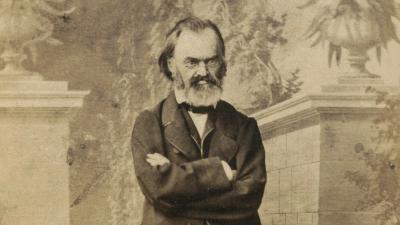

At the beginning of the second course of the Paris Lectures, Adam Mickiewicz presented to the audience the general programme of lectures he intended to give. He took the opportunity to share with them the unique hopes he had for the part of the course devoted to philosophical problems, which he had postponed for a time and which was to crown the second year of lectures:

"All Slavic countries in general are now in solemn expectation. They are all awaiting a universal idea, a new idea. What will this idea be? Will the Slavs be drawn into the conquering ways of Russia, or will the Poles manage to carry them along in their bold march towards that future which the Russians call a dream, the Czechs a utopia, but which is only an ideal? Will there be any concessions from both sides? Will there be a formula capable of satisfying the needs, interests and aspirations of all these peoples? This momentous question will occupy us this year. As a Slav and as a witness to a movement that is shaking philosophy, shaking the minds and hearts of the peoples of the West, I feel an inexorable pull towards this part of the course, which I have, however, decided to postpone. It is, I think, the only part that will be of current relevance to the French, because the old West is also in a state of expectation. All philosophers say that we are in an age of transition. It will be an age of reconstruction according to some publicists, an age of rebirth according to others. But they all believe in some kind of palingenesis, some kind of transformation. Today's epoch presents itself to your poets as twilight; they ask what tomorrow will be like. Will it be the dawn of a new world or the west of an ending world?".

The audience received a foretaste of these reflections, which Mickiewicz foreshadowed, already in the last lecture of the first course of the Paris Lectures. The Polish poet concluded the first year of lectures on Slavic literature at the Collège de France by delivering his opinion on the fact that the political order that had been created in Europe as a result of the Treaty of Westphalia had led to the gradual marginalisation of Poland and the reorientation of European policy towards Russia. Mickiewicz made the philosophy that developed after the Treaty of Westphalia an important part of the spiritual (for it was not exclusively political, after all, since the orders of politics and spirit are essentially inseparable) panorama in which Poland gradually disappeared. According to the Collège de France lecturer, the reasons for Poland's predicament were to be found in the materialism that underpinned both the political and spiritual (philosophical) order of the new Europe. In this order, Poland is regarded as "an enemy because it opposes the advance of the spirit of materialism, because it opposes traditions, because it puts up barriers and because it tries to preserve its own existence, irreconcilable with the new aspirations" . German idealism (in a way contrary to its suggestion) did not, however, change this state of affairs, but developed it even further - the Polish poet saw an intensification of negative tendencies for Poland in Hegel's system and its political consequences. It appeared, therefore, that after the Treaty of Westphalia a significant contradiction had been created between the aspirations of Poland and other European nations. Mickiewicz stated: "Thus the whole political and philosophic march of Europe is even opposed to the political and religious march of Poland. What wonder, then, that this nation, separated from all states, insisting on developing its own principles, unable to gain any strength, any help either from Rome or Paris, fought against even by the whole of philosophy - what wonder that all the minds of this nation are beginning to weaken and waver; that Poland feels the need to concentrate within herself in order to recognize her enemies, and that, beaten down, she seeks a way into the future?".

Such statements about philosophy were possible because Mickiewicz very clearly saw and felt that in the course of its development it had acquired the characteristics of an ideology - he perceptively observed that in modern times philosophy had become responsible for the formulation and justification of goals that were to motivate collectives to take specific actions. In it, therefore, there was also to be found "the mysterious word that shakes nations and impels them to action, that which Tacitus called arcana imperiorum", and which Mickiewicz sought to "discover, to find" in his lectures. At the same time, philosophy was a false word, a counterfeit of revelation, and - as we find, for example, in the last lecture of the first course - its falsity was also revealed in relation to the Polish question. The Polish poet, however, did not deprive his listeners of hope, did not leave them with a bad past and present, but spread before them new perspectives, opened them to the future, looked forward to a fundamental, radical newness. Already in the last words of the first course - closely corresponding to the quoted fragment of the first lecture of the second course - he was announcing to them that in the following year it would become apparent how "[...] Poland, not only forgotten, but even with inexorable necessity fought against by the system now prevailing in Europe, will put up against this onslaught from all sides an idea drawn from within its nationality".

The Paris Lectures are rightly regarded as the most significant, integral and comprehensive presentation of Adam Mickiewicz's philosophical worldview. The Polish poet's pronouncements on philosophical themes during the lectures contain, on the one hand, a radical critique of philosophy itself, and, on the other, an attempt to replace it with a different, new idea that would spur nations into action. The excerpts from the last lecture of the first course discussed above perhaps most emphatically reveal one of the characteristic inclinations of Mickiewicz's arguments and interpretations: the philosophical issue is closely connected in his work to the Polish question, to the question of Poland and its independent existence. These two issues prove inseparable, just as the spiritual and political orders are inseparable. The new philosophy, the philosophy of the future, is to open up completely new prospects for Poland, different from those created by the philosophy of the past and the present, which condemned Poland to aim for non-being and to persist in non-being.

Let us ask one question that will take us beyond the strict context of Mickiewicz's statements themselves and lead us to the fundamental question of this text - the question of independence as a philosophical category and as a particular criterion for assessing the credibility of philosophical views. Let us ask, namely, whether the close connection that is evident in Mickiewicz's work between the evaluation of philosophy and the issue of Polish independence, and whether the direct introduction of the issue of Poland and its rebirth into considerations devoted to philosophical issues, can be theoretically justified? In order to answer this question, let us take it back to this singular example, which is the worldview developed by Mickiewicz in the Parisian lectures, and let us first ask whether this unification is defensible on the basis of the position Mickiewicz outlined in the Parisian lectures, or whether it is merely an expression of subjective predilections, devoid, however, of strictly theoretical significance? Does Mickiewicz appear here only as a poet longing for Polish independence who mobilises Poles to action, or is he also, in this view, a penetrating thinker, a critic of past and present philosophy and the founder of a new philosophy?

The answer, according to which Mickiewicz here gives vent to a merely theoretically irrelevant reaction to the position he was in as a Polish émigré, and therefore according to which he gives vent to his purely adventurous position, unworthy of being raised to the level of a philosophical problematic, seems to impose itself. We are so deeply rooted in the tradition of universal philosophy that we intuitively faintly sense this connection, which for Mickiewicz was a self-imposed union of two closely related elements of the discourse he was developing. And besides - this matter is fundamental to this pre-reflexive rejection of the philosophical legitimacy of the Polish poet's identification of the Polish question with a philosophical issue - we live in a dense network of thoroughly false diagnoses about Polish messianism, We are living in a dense network of thoroughly false diagnoses of Polish messianism, leading us to perceive in it a manifestation of national megalomania or a collective psychosis, an unjustified reaction of our ancestors to collective suffering, and this in spite of the great work done by such scholars as Andrzej Walicki and Stanisław Pieróg to reject this profoundly false assessment of messianism. Yet Mickiewicz's thought also turns out to be strict, subordinated to mental precision and profoundly rational in this element of it - perhaps the most theoretically problematic of its many problematic assumptions. There are at least two conclusive arguments in favour of the thesis that, if Mickiewicz wished to maintain the basic coherence of his position, he not only could, but indeed had to, fuse theoretical considerations with the Polish question. For this is due, firstly, to the aspiration, fundamental to his worldview and repeatedly defended in polemics with other philosophical views, to identify truth and good with one another. It was this identification that must have led him to the conclusion that only those views could be considered true which did not lead to the sanctioning of the unjust fate that had befallen Poland. Truth has a moral dimension and moral overtones, there is no truth acquired outside of the good, sanctioning evil both in relations between individuals and collectives - this is how this fundamental view can be formulated. The attitude to the cause of Poland's independence could therefore be regarded as a theoretically legitimate test of the truthfulness of philosophical views, and a contrary view could only be accepted at the price of tearing apart this identity of truth with goodness. A clear moral consciousness - an awareness of the historical evil that had befallen Poland - was also required for this.

All this should not surprise us if we turn our attention to the second argument in favour of the thesis that preserving the coherence of one's position required Mickiewicz to unite his theoretical reflections with the Polish question - it is directly connected to Mickiewicz's philosophy of action, which in its metaphilosophical dimension proclaims that it is unjustifiable to separate the spheres of cognition and action, theory and practice. Knowing and doing are one - this is one of the most essential convictions defended within the Mickiewiczian worldview. In the philosophy of action, Mickiewicz's view of the identity of truth and goodness gains epistemological grounding - it is inscribed in Mickiewicz's fight against the abstract (primarily the one characteristic of German idealism) view of the subject of cognition in favour of a concrete view that shows him as a spirit being the subject of spiritual and moral perfection. Mickiewicz's philosophy of action (this is its fundamental feature) reaches back to the fundamental experience of the spirit, to the experience of its growth and elevation towards truth, and it is through this that it recovers what constitutes the basis of action - the certainty of truth.

Within a philosophical worldview based on these two assumptions - the identification of truth and goodness and cognition and action - not only could, but at that moment in history (for the philosopher is not an ahistorical subject of cognition, immersed in contingency and finitude, and therefore his reflection inevitably also reflects the time and place in which he creates), there had to be a close fusion of the Polish question with the philosophical issue. In this respect, Mickiewicz's Messianism from the Paris Lectures represents the pinnacle of Polish philosophy at the time of the Partitions. It proves that the idea of independence also contained a philosophical and ethical charge - that it could become a category of philosophical thinking and ethics. It provided a concrete criterion that worked by bringing thinking itself into an agatological horizon, orienting it towards a specific ideal and its associated ideals. This, in turn, enabled it to have an impact outside its strict domain - to give a general orientation also to those views that do not directly confront the question of independence and do not pose it as a philosophical problem. However, in order to appreciate the value of independence as a philosophical idea that also organises philosophical discourses not directly related to it, one must first note that the philosopher always creates within a specific political and national community, sharing its fate.

This text was first published in Teologia Polityczna Co Tydzień 2018, no. 136 and is available online at the following link: Tomasz Herbich: Niepodległość a filozofia. Wokół pewnego wątku prelekcji paryskich Adama Mickiewicza - Tomasz Herbich (teologiapolityczna.pl).

Comments (0)