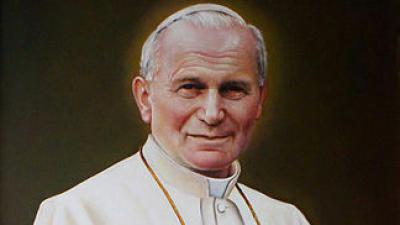

Solidarity in Chile - an Unfinished Project. The Contribution of John Paul II

Speech delivered during "John Paul II. An Inspiration for the World" Congress organized by the Polska Wielki Projekt Foundation, October 1, 2023 Kraków, Poland.

Much has been written about the presence of John Paul II in my country[1]. What we will try in these brief minutes is to make an evaluation from the point of view of culture, to see how and what extent the thought and action of the Polish Pontiff has influenced the being and acting of Chileans and how this contribution is shaping up in the future.

John Paul II's presence in Chile dates from 1978. Indeed, in that year, when "a man from afar" assumed the Papacy under the name of John Paul II, Chile and its neighboring country, Argentina, were on the verge of war over a matter of territorial claims. Argentina had disregarded an Arbitral Laudo from Great Britain. That Laudo stated that three islands in southern Chile were Chilean.

On December 22, 1978, Argentina planned to invade those islands. If this had happened, it would have generated a war between brotherly countries with unforeseeable consequences.

Two months after assuming as Pontiff, John Paul II, faithful to his deep understanding of the human being and the fact that "the person is manifested in action", offered papal mediation and stopped the war two hours before it began. The intervention of the papal envoy, Cardinal Samoré, was decisive. That was the first time that Chile would be directly protected not only by the thought but also by the action and spiritual strength of John Paul II.

Years later, during the eighties of the twentieth century, Chile was involved in endless protests demanding the return to a democratic regime. We were under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. The coup d'état had taken place in 1973, a period in which the socialist Salvador Allende governed, who, although he had democratically come to power in 1970, had turned his mandate into anarchy and was emerging as an increasingly totalitarian regime. The causes of this are multiple and beyond the scope of this study, but the effects were no less real. As an example, we can name what happened with the Statute of Constitutional Guarantees that the Congress had made Allende sign to authorize his mandate; the fact is that Allende ignored and gradually began to take away these constitutional guarantees, intervening in the banking system and companies, statization of agricultural lands, establishing a Supply and Price Control Board (JAP) that determined what each family should consume. At the time of establishing the JAP, it was stated in its introductory decree: "the JAP will define the real requirements per family". On the other hand, an attempt was made to establish a Marxist National Unified School (ENU). From the economic point of view, inflation broke out. Chaos and protests soon made Chile an ungovernable country with unbridled violence coming from practically all political sectors to a greater or lesser extent.

In this sense, the coup d'état, led by a Junta headed by Pinochet, was among the situations that, given the events, could be seen coming, although it was not what many wished for, just as it was not what many wished for Allende to continue.

The Pinochet dictatorship applied an iron fist from the beginning. Disappearances, executions, and torture were commonplace. The Catholic Church created the Vicariate of Solidarity (Vicaría de la Solidaridad) in 1976, which provided legal assistance to victims of repression. Human Rights violations and abuses were an unresolved problem for the military government. Indeed, when democracy returned, the Rettig Report, delivered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission created by President Aylwin, the first president of the nascent democracy, counted more than 3,000 people murdered or disappeared until 1991.

Thus, during the eighties, as we have already mentioned, there was significant popular discontent with protests that involved the death of several people each time one of them took place.

However, according to the constitution drafted by Pinochet, a plebiscite was to be held in 1988 to decide who would rule the country for the next decade. A year before this plebiscite, Pope John Paul II visited Chile. For the second time, the Pope participated directly in the life of the Chilean people.

To participate is well said, especially if one remembers that for Karol Wojtyla, participation was to take an active and organic part in the life of others and to have others take part in our life. Such participation, for Wojtyla, consists, moreover, in being a property of the person and a constitutive of community, that is, there is no community without participation. And for Wojtyla, the attitude and social virtue proper to participation is solidarity. In this sense goes also Max Scheler's consideration of solidarity as the radical moral unity of humanity in responsibility and guilt, so that we are all co-responsible for all; that when one does not act for the good of another, he is guilty of not doing so if it is in his power to do so. With his actions, Karol Wojtyla/John Paul II reminded us Chileans of these and many other things, perhaps not in the way of academic teaching, which as we know he exercised well and very powerfully, but in the way of virtuous example; of a virtuous ethos of solidarity, a way of living in the world that does not fail to fulfill its duty and that asks for the right conditions to exercise that duty.

John Paul II, then, participated directly for the common good of Chileans. In fact, his visit, which took place between April 1 and 6, 1987, in such difficult circumstances, was long awaited. At that time, as now, Catholics were divided politically and doctrinally. Some, a few, supported extreme forms of liberation theology that had assumed Marxist analysis and method. Others, the great majority, wanted peace and identified with political currents of the center. Another minority supported the Pinochet regime. It was in this context that the Pope came to Chile. And he spoke clearly, reminding us that we Chileans had "vocation for understanding and not for confrontation".

It was a visit, however, not without its difficulties. Significant was what happened during the beatification mass of the first Chilean woman saint, Sister Teresa de Los Andes, which the pope celebrated in Parque O’Higgins:

Suddenly, the enclosure that shortly before had been filled with prayers, songs and the voice of Wojtyla, was usurped by tear gas, barricades and violence. Not only the water cannons and the security forces confronted the protesters who threw all kinds of objects against the crowd, but also the religious present in the audience and the papal guards. The mass stopped for a few minutes, during which the organizers recommended John Paul II to leave the enclosure. However, he decided to stay and continue with his speech. As the disturbances continued in the background, the Pope uttered his most iconic phrase of the trip: Love is stronger!

Once the ceremony was over, when John Paul II was to leave Parque O'Higgins, he took a few minutes to kneel down and pray on the same stage. The image of the Pope holding his head with both hands and with his penetrating gaze towards the public remained as the postcard of that afternoon[2].

Joaquin Navarro-Valls, Pope John Paul II's spokesman, said that at the end of the Mass approached to the Pope the Chilean Cardinal Juan Francisco Fresno and said, "Holy Father, forgive us", "But the pontiff replied: 'Why? your people have followed the ceremony, they have participated in the Holy Mass. The only thing not to do in these situations is to surrender to the agitators'". And later the pope told those present: "I congratulate you for having acted as Christians in the face of violence"[3].

That phrase, "Love is stronger", struck a deep chord among Chileans, who were once again reminded that we are a peaceful but strong people. And that the only way to live humanly is mediated by love. The Wojtylian maxim "the person must be affirmed by his own sake", persona est affirmanda propter se ipsam, was evident here. Wojtyla himself had recalled in his book Love and Responsibility that this personalistic norm of action is nothing other than the translation in the field of ethics of the evangelical "love one to another".

During his visit, the Pope met with ecclesiastical organizations, but also with civil and political society. Of course, the private interview with Pinochet is well remembered. What they talked about remained a secret, but years later, John Paul II's private secretary, Cardinal Estanislao Dziwisz, recalled that meeting and said that the pontiff told Pinochet: "If you are Catholic, here you have to build a democratic government".

However, the following year Pinochet called a plebiscite in which he was the only candidate. He lost and then a year later free elections were held, returning Chile to a democratic regime.

But the Pope's trip, eminently pastoral, also consisted of meetings with the world of culture at the Catholic University of Chile and with economists at the United Nations' ECLAC in Santiago de Chile. With the poor people, the indigenous peoples, and the youth.

I would like to dwell on two of these visits: to the world of culture and to ECLAC. At the Catholic University, the Pope reminded us that "man lives a truly human life thanks to culture" and that the essence of every culture corresponds to the attitude with which a people affirms or denies a religious bond with God, "which leads "religion or irreligion to inspire all the other orders of culture -family, economic, political, artistic, etc.- insofar as it liberates them towards an ultimate transcendent sense or encloses them in their own immanent sense" (Puebla, 389).[4]

And faithful to his practicality, he further noted:

In concrete terms, this means promoting a Culture of Solidarity that embraces the entire community. You, as active elements in the conscience of the nation and sharing responsibility for its future, must take charge of the needs that the entire national community must face today. I therefore invite you all, men of culture and "builders of society", to broaden and consolidate a Current of Solidarity that will contribute to ensure the Common Good: bread, shelter, health, dignity, respect for all the inhabitants of Chile, listening to the needs of those who suffer. Give full and free expression to what is just and true and do not shy away from a responsible participation in Public Administration and in the defense and promotion of Human Rights.[5]

He thus exhorted the people of the world of culture, recognizing that at this time there was "a certain disorientation and insecurity," but that the responsibility to seek the truth and the good was inescapable. A truth that has its fullest fulfillment in not abdicating the religious dimension of existence: "Without the immovable identity of the Christian faith, external borrowings become easy and transitory syncretisms that time dissipates"[6], the Pope concluded so his message.

On the other hand, in his speech to the delegates of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the Holy Father focused on the issue of extreme poverty in Chile and Latin America. There he called on Latin Americans to build an Economy of Solidarity, because when solidarity is practiced and possessed as a fundamental attitude, one feels the poverty of others as one's own and a just relationship can be considered, also between State and business:

But the State and private enterprise are ultimately made up of persons. I want to emphasize this ethical and personal dimension of economic agents. My appeal, then, takes the form of a moral imperative: Be in solidarity above all else! Whatever your role in the fabric of economic and social life, build an Economy of Solidarity in the region! With these words I propose for your consideration what I called in my last World Day of Peace Message "a new kind of relationship: the social solidarity of all.[7]

Then, the Pope exhorted us with that moral imperative that remained resonating in Chileans for decades: "The poor cannot wait!" For both the State and companies are made up of people, just as the poor and unemployed are not an abstract concept either but are people who demand from us a moral and also a technical response.

Finally, John Paul II reminded us of the profound relationship between the Principle of Subsidiarity and the Principle of Solidarity. Faced with a reductionist Principle of Subsidiarity present in the economic policies which had led to the economic prosperity of the country, but implied a high social cost that would later, according to the economists of the regime, be remedied by an overflow that would make this prosperity reach everyone, the Pope pointed out: "Those who have nothing, cannot expect relief that comes to them through a kind of overflow of the general prosperity of society"[8].

Let us recall that this conjunction between solidarity and subsidiarity would later be taken up by Benedict XVI in Caritas in veritate, affirming that subsidiarity without solidarity leads to social particularism and that solidarity without subsidiarity leads to mere assistentialism. The same thing happens when Francis speaks of the Culture or anti-culture of Discarding and proposes as an antidote the Culture of Encounter and Care, thus showing a continuity in the thought and action of the three Pontiffs.

Undoubtedly we can affirm, in conclusion, that the presence of John Paul II was decisive in the 1980s in terms of remembering our Chilean identity as religious, welcoming and with a vocation of understanding. Likewise, he had important political influences for our return to democracy and to propose to us, in economic and social-cultural terms, that the good life of the gathered multitude cannot be achieved without solidarity.

Today, fifty years after the coup, however, things have changed in Chile. Indeed, the Current of Solidarity" has been limited in a reductionist and ideological way and we are once again quite divided and faced with totalitarian dangers of different kinds. The events that have taken place since the social explosion (Estallido Social) because of a cracked social fabric have confronted us. For various reasons that we cannot analyze here due to the limited time, we can say that solidarity appears today as an unfinished project. To complete it requires recognizing that History is cyclical, that History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. And what we can do is to always recall anew the characteristics of a Community of Persons, the Communio personarum, so dear to Wojtyla.

The last years faced with the proposal of a new constitution for Chile, with clearly totalitarian overtones, the memory of solidarity in Wojtyla was once again necessary[9]. Chileans rejected it by a majority. We will have to see the new constitutional proposal, not by a Constituent Assembly but by Congress. In this sense, the memory of the dignity of the human person that must affirm by her own sake, of solidarity, of the economy of solidarity, the constitution of communities of persons, must always be carried out. Even if at times it seems that there are no immediate concrete results. Remembering Rocco Buttiglione, the struggles do not end. Sometimes we win and sometimes we lost. But surely the only struggle that is effectively lost is the one that is not fought. In this sense, we Chileans, like the Poles, know how to recover from apparent defeats. This is what John Paul II repeated to us during his visit. And something else he said that drives us to fight again and again: “Love always wins”. “Love can always do more”.

[1] Cf., for example, Larios, Gonzalo, "El amor es más fuerte. Alcances políticos de la visita de Juan Pablo II a Chile”, paper read at the International Scientific Conference: "Puerta hacia la libertad. III Pilgrimage of John Paul II to Poland" held in Warsaw on May 25, 2012, organized by the John Paul II and Primate Wiszynski Museum and the John Paul II Institute. It was published in a bilingual Polish-Spanish edition in: Gateway to Freedom, III Pilgrimage of John Paul II to Poland, John Paul II Institute, Warsaw, 2012, pp. 55-79.

[2] https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2018/01/11/890638/Disturbios-en-el-Parque-OHiggins-y-recorrido-por-regiones-Asi-fue-la-visita-del-Papa-Juan-Pablo-II-a-Chile-Parte-II.html

[3] Navarro-Valls, Joaquín, Mis años con Juan Pablo II, Notas personales, Espasa, E-book, España,2023, pág, 77.

[4] DISCURSO DEL SANTO PADRE JUAN PABLO II A LOS REPRESENTANTES DEL MUNDO DE LA CULTURA

Universidad Católica de Santiago de Chile Viernes 3 de abril de 1987. N°3.

[5] Ibid, N°4.

[6] Ibid, N°8.

[7] DISCURSO DEL SANTO PADRE JUAN PABLO II A LOS DELEGADOS DE LA COMISIÓN ECONÓMICA PARA AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE (CEPALC) Santiago de Chile Viernes 3 de abril de 1987. N°6.

[8] Ibid, N° 7.

[9] See, for example, the analysis made by the author in a document of the Social Union of Christian Entrepreneurs (USEC): THE PROPOSAL FOR A NEW CONSTITUTION IN THE LIGHT OF THE DSI: SOLIDARITY, Bulletin of the Social Union of Christian Entrepreneurs, USEC. (2022), https://www.usec.cl/wpcontent/uploads/2022/08/4_v2_Usec_articulos_EmilioMoralesdelaBarrera.pdf. Analysis presented in different Colloquiums and Radio Programs.

Comments (0)