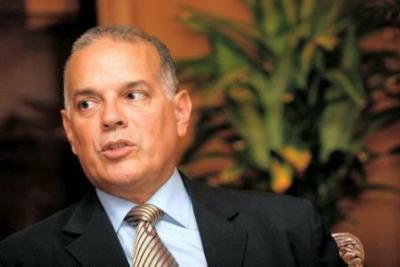

Alejandro Peña Esclusa: “Fraud is a crucial issue for the future of democracy in the West, because democracy is literally being stolen from us”

Interview with Alejandro Peña Esclusa, engineer, writer, analyst and political consultant. A pioneer of the first protests in his country against the Chavista regime, he was imprisoned for a year in El Helicoide (a prison notorious for its torture) and is still a political prisoner of conscience. An expert on the Sao Paulo Forum, he has written several books on the subject and has just published “Los Fraudes Electorales del Foro de Sao Paulo” (The electoral frauds of the Sao Paulo Forum).

Álvaro Peñas: Unfortunately, it is increasingly common to hear the word “fraud” after an election. How do these new frauds differ from the old ones?

Alejandro Peña Esclusa: Modern electoral fraud is advanced, comprehensive, exportable, evolving and can be carried out not only by the government, but also by the opposition. This model was developed in Venezuela by the Cubans with Chávez’s consent, because Venezuela has been a laboratory of the Castro-communist regime for many things, from methodologies of social control to new forms of corruption. This mechanism of electoral fraud has been tried in 29 elections in Venezuela: presidential, governmental, regional, local and referendums. And it is being exported to other countries.

In other words, there has been fraud in all Venezuelan elections.

In all of them and more and more. It is a new technique that has been evolving and for which the democratic sectors have not developed antibodies, have not kept up to date. This electoral fraud has four novel aspects that did not exist fifty years ago, because before, fraud consisted of stealing votes at the polling stations. The first is the use of computers, in the electronic voting machines and, where votes are still counted manually, in the counting machines. This software has been exported and several companies are involved in scandals, such as Smartmatic, Indra or Dominion. Another aspect is the manipulation of public opinion through social networks. These networks play a very important role in elections because they dictate trends and can make the public believe that a candidate has more support through the use of bots. For example, Elon Musk, the CEO of Twitter, alleged that Russian operators used social media to favour the leftist Petro’s campaign in Colombia.

The third factor is the modern use of social engineering, the cultural warfare used to manipulate the public mood and eliminate opponents. In Colombia, a process of social engineering came to light, the so-called “petrovideos”, to demolish their opponents using dirty warfare. A very well orchestrated campaign with technicians specialised in manipulating public opinion through rigged polls, fake news, opinion trends, etc. Finally, the fourth aspect is the influence of drug trafficking, which is buying electoral campaigns and candidacies on a large scale. The most extreme case is that of Venezuela, whose president is the head of the Cartel of the Suns and has a fifteen million dollar reward for his capture. For this reason, Gustavo Petro, as soon as he won the elections, promoted the legalisation of drugs, even in the United Nations, because he was paying a favour. Not forgetting that the M19, the group to which Petro belonged, assaulted and set fire to the Palace of Justice in the service of drug traffickers.

You mentioned that in cases of manual voting, the fraud takes place in the counting machines. But in those cases, you could do a real recount by adding up all the votes.

That is true, but in many places there are no representatives of the democratic parties because they are dangerous areas. For example, in Colombia, the Gulf Clan threatened opponents of Petro with violence; in Peru, we have violence in the highlands; in Venezuela, the government’s armed groups threaten opponents with death. To avoid fraud in the recount, it is necessary to have representatives at all polling stations and access to the ballot boxes to compare them with the electoral records. That is why the left creates the conditions so that in a large number of polling stations there are no opponents or the ballot boxes cannot be opened, and that is where the fraud takes place.

Don’t you think that, in many cases, democratic parties simply don’t dare to question the electoral system and accept the result knowing that fraud has taken place?

Yes, there is a fear of denouncing fraud. The Sao Paulo Forum has a whole strategy to frighten and attack those who say there is fraud. Anyone who does not recognise the results is immediately accused of being a sore loser and not being a democrat, and through social engineering anyone who questions the elections wants to destabilise democracy. I devoted a chapter of the book to the judicial persecution of those who denounce fraud, and one has to be very brave to say that there is fraud. It is curious that in a democracy it is considered a problem to denounce and count all the votes. In the case of Colombia there is an aggravating factor: the people in charge of counting the votes in the last elections belonged to the Federation of Educators (FECODE), and the leadership of this organisation came out in favour of Petro.

In the case of Brazil, there were reports that in certain areas of the country there were results of 100% of the votes in favour of Lula, something statistically impossible. Bolsonaro wanted to reform the electoral system, but the highly politicised judiciary prevented it. What happened in Brazil?

What happened in the north of Brazil, with polling stations with 100% of the votes for Lula, also happened in Venezuela with Chávez, in Bolivia with Evo Morales in 2019, in the highlands of Peru with Pedro Castillo, or with Petro in Colombia in areas controlled by guerrillas or paramilitaries. In my opinion, it is the same scheme that was developed in Venezuela and exported to other countries. In the case of Brazil we must also add the international campaign in favour of the left and against Bolsonaro. There was a fierce campaign in which the Brazilian president was accused of wanting to stay in power, of being a criminal and a coup leader. An atmosphere was created in which if Bolsonaro questioned the results, it would confirm what the social engineering had predetermined, that he was a coup-maker. There was no serious investigation in Brazil, nor has it been allowed, and this fact is a sign of guilt. The first person interested in opening an investigation should be Lula, but we don’t know what happened, we only have indications. In my book I mentioned a very clear one, when Daniel Ortega imprisoned his seven opponents at the end of 2021 and proclaimed himself the winner of the elections, Lula and his party recognised the results and congratulated Daniel Ortega. This indicates that if they are capable of endorsing fraud in Nicaragua, they could do the same in Brazil.

The case of Brazil is also a clear example of a fraudulent takeover by the opposition. This was made possible by the takeover of part of the Brazilian judiciary, the same judiciary that facilitated Lula’s release from prison for political reasons, not because he was innocent. That same judicial sector that freed Lula is the one that has prevented investigations from being carried out. So, you don’t have to be a government, you simply have to control some areas of the country in order to do fraud in those areas and in that way you get part of the votes. The other part you get with dirty war: attacking Bolsonaro’s figure for 5 consecutive years, accusing him of burning the Amazon, of being an ultra-right-winger, blaming him for the Covid deaths… making a fierce campaign to be able to justify Lula’s triumph later.

You have quoted Gustavo Petro and the Colombian elections several times.

Yes, because the case of Colombia is the most sophisticated case of fraud in the 21st century. We have the extreme case of Daniel Ortega, who commits fraud in broad daylight and can do it because he controls absolutely everything, but in Colombia the opposite happened. Petro was in the opposition in a country traditionally opposed to the left and which has fought for 60 years against the armed guerrilla groups to which Petro belonged, that is to say, the institutions were an obstacle to being able to commit fraud. However, there were several key elements. First, the bias of the electoral authorities. This was demonstrated in the campaign when the national registrar Alexander Vega handed over the recount to Indra by hand without having the tender and computer glitches occurred that favoured Petro by one million votes. Then, the social engineering campaign to demoralise Colombians and present that everything was wrong. Also the illegal financing. Petro had more money and more proxies than all the other parties put together. And to all this you add the false polls, the Russian operators that Elon Musk denounced, the petrovideos and the use of violence in certain sectors of the country to intimidate those who voted against Petro. When you add up the extra votes that Petro may have received because of all these irregularities, because of all these different forms of fraud, you realise that, if it had been a clean and transparent election, Petro would have lost.

Moreover, in Colombia, as also happened in Chile, the elections were held after vandalism demonstrations that instilled terror in the population, called by the candidate Petro. It is a very clear message, either you vote for the left or the riots will not stop. There can be no free elections if citizens are threatened, in this case by vandals called the “First Line” whose leaders have been released by Petro after his arrival in government, which shows complicity. That cannot be a valid election.

Could this model of fraud come to Europe, and do we have to start worrying about counting and voting machines?

Yes, because it is an exportable model. In Kenya, just before the elections, two Venezuelans from Smartmatic were arrested at the airport with election material. There are reports of similar frauds outside Latin America, with blackouts of the counting machines as happened in the United States.

How can this fraud be dealt with?

The best answer, ideally, is what Germany did, where the Constitutional Court banned electronic voting. Other developed countries also prohibit it because e-voting can be manipulated. But to combat fraud, the first thing to do is to understand how it works, to prepare before the elections and not to believe that it is enough to campaign to get the vote. Then two things are needed: a nationwide citizens’ structure to monitor the polling stations, to count the votes one by one, to guarantee the veracity of the results; and an international electoral observatory to be able to detect fraud, like the group of experts who discovered fraud by statistical inconsistency in the 2004 referendum in Venezuela.

In the book’s foreword, former Colombian President Andrés Pastrana argues that democracy is on the verge of disappearing because electoral fraud violates the right of citizens to elect their representatives. It is true, fraud is a crucial issue for the future of democracy in the West, because democracy is literally being stolen from us.

photo: http://fuerzasolidaria.org/

Read also

Nacho Montes de Oca: “The best way to disarm the Russian propaganda is to go back to the basic point, which are values”

Nacho Montes de Oca is an Argentinean writer and journalist, known for his books of essays dedicated to historical research and analysis of wars and other contemporary conflicts.

Álvaro Peñas

Corruption in Portugal: The never-ending story

Portugal’s political news is not free from the spectre of corruption. Of course, there have been other important news items, such as the adoption of euthanasia, mentioned at the end of this article, but the succession of corruption-related news items occupies the front page of all the newspapers.

Álvaro Peñas

The Battle for History

Despite the European Parliament’s condemnation of communist totalitarianism, “progressive” governments try to erase the memory of its victims.

Álvaro Peñas

Is a European Strategy Possible?

At the end of July I attended a talk with Balasz Orbán, political director of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and author of the book “The Hungarian way of strategy”. The talk covered a number of topics that can certainly help to understand the political strategy of Viktor Orbán’s government and the reason why he is supported by the majority of Hungarian people.

Comments (0)