“War has uncontrollable consequences”, noted historian Steven Mintz in Inside Higher Education in January 2023.[1] Shortly afterwards in the same journal, Mintz argued that American academic scholarship is stagnating.[2] These two statements summarize the reasons why the long-smoldering idea of decolonizing Slavic Studies has recently been brought to light.

The proposition to decolonize Slavic Studies began to gain traction at the very end of the decolonization process that has been occurring worldwide since mid-twentieth century. In the United States, the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies, which has long tolerated colonialist scholarship about non-Germanic Central Europe and Eastern Europe, has joined the bandwagon and dedicated its 2023 Virtual Convention to that theme.[3] It took the Russian-Ukrainian war and its “uncontrollable consequences” to make acceptable the idea of placing Slavic Studies under the microscope of decolonization. “No event has transformed the continent more profoundly since the end of the Cold War, and there is no going back now”, noted Roger Cohen in the New York Times at the outset of the second year of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.[4]

Why should such a process take place? First, because the current situation does not reflect the real weight and importance of literary and cultural activity in non-Germanic Central Europe and in Eastern Europe. The war in Ukraine began to tear off the curtain that obscured a world of which American and European students of things Slavic have had no idea. Second, because the war in Ukraine is rearranging the relative political weight of non-Germanic Central Europe and Eastern Europe. Yes, I do recognize the importance of nuclear ICBMs in Russia’s possession, but I also recognize the realities of Ukrainian courage and willingness to sacrifice for the preservation of Ukrainian identity. I also recognize the richness of intellectual landscape in places that until now have been dismissed as “Eastern Europe.”

As things stand now, Slavic Studies in the Western world are really Russian departments, and it can hardly be expected that the Russian-literature-and-language teachers will be mobilized to act against their self-interest. Decolonization of Russian studies means a reduction in the number of those who are accustomed to instructing students that there is nothing except Russia east of the Oder River. Any attempt to diminish the predominance of Russian studies at Western universities has met, and will meet, with their protests. Dozens of reasons will be set forth to defend the status quo. Sarcasm and derision may be employed to disqualify the works of authors writing in languages neglected by Western scholarship.

How did Russian Studies fall into the trap of colonialism? Let us consider this using the example of American universities. Before World War 2, Russian subjects were seldom taught in America. During the Cold War universities hastily created departments or centers for “Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies,” as if countries such as Czechoslovakia or the Baltic republics had any connection to “Eurasia.” The “Eurasian,” “Slavic,” and “Eastern European” label had “Russian studies” as its real center. At smaller universities, Russian subjects were taught in such administrative units as “Modern Languages.” At Ohio University where I started my American education, the Russian team consisted of a British colonel (ret.), who mastered the rudiments of Russian during his service in the army; a Hungarian refugee with a pronounced post-traumatic stress syndrome; and myself, a graduate student in English. Ohio University was an exception in that none of us came from the USSR and we were not brainwashed by Soviet-style education. Much more common was the situation where American admirers of Russia’s power or former Soviet citizens offered their services to universities thus introducing, consciously or not, a Russian-style interpretation of history, literature, and the arts in the USSR. These Russian-Soviet acquisitions were not interested in broadening the field of Slavic Studies; rather, they worked to narrow it down to Russian Studies. There existed at America’s best universities chairs of non-Russian Slavic Studies, sometimes funded by the professors who taught these subjects (such was the case with the chair of Polish studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison). At other times, such chairs were funded by perspicacious university administrators. By the 2020s, these chairs have either disappeared or were reduced to language teaching: PhD programs in Slavic Studies require a non-Russian Slavic language and literature to be among the courses PhD candidates have to take.[5]

In the 1950s and ‘60s, practically anyone speaking Russian with reasonable fluency was welcome at American centers of learning. And not just for language teaching. Particularly welcome were educated refugees from the Soviet Union who, it was presumably assumed by deans and presidents of universities, were all opponents of the communist state. Many doubtless were, others might have been opportunists, still others fake refugees. They imprinted in the minds of their students such “truths” as “Russia extends from Eastern Europe to Sakhalin and the Kurile Islands”. Of course they were not the only source of such an erroneous view: in postwar years, books and studies by Russian/Soviet sympathizers were produced at an amazing speed by American academic scholars enchanted by nineteenth-century Russian literature and tourist experiences in Moscow and Leningrad.

The Sovietocentric view has partly been shaken off due to the fall of the USSR, but the Russocentric orientation remained. The USSR disintegrated more than a generation ago and with it, some narratives that proclaimed its strength. I would argue, however, that the tenure-protected armchairs still harbor those whose admiration for the USSR has not entirely evaporated. On September 18, 2020, New York Times stated in its obituary of historian Steven Cohen that he was “an influential historian of Russia”. It was an understatement. Fifteen years prior, or in the year when Gorbachev came to power, Professor Cohen published Rethinking the Soviet Experience: Politics and History since 1917, which argued that, despite certain faults and mistakes, the USSR was a rock-solid entity. In an earlier book, Cohen argued that, had Bukharin rather than Stalin come to power in the USSR, democracy would have prevailed in the former empire of the tsars. Cohen taught at Princeton for 30 years (1968-1998), and at New York University for another decade. He influenced several generations of students, many of whom are teaching to this day all over the world. None of his books betrays an awareness that the USSR was a colonial empire and that virtually all non-Russian nations within it have been looking for opportunities to get rid of Russian rule. The problem of suppressed identities did not exist for Professor Cohen. Although Rethinking the Soviet Experience was a vigorous defense of a system that competed with Nazism in its inhumanity, Cohen was not rebuked in any way by the “Slavic” profession. Nor has Rethinking the Soviet Experience been ever “rethought” by its author. He never said “I may have been wrong” to those of us who also taught Russian subjects. His legacy, supported by his sizeable financial donation for scholarships in the “Slavic” field, lives on in the professional organization that benefitted from his generosity. While there exists a well-deserved stigma concerning the writings of Nazi sympathizers, no such stigma has ever been attached to those who sympathized with the Soviet regime and tried to persuade others to do likewise. Professor Cohen symbolizes one of the reasons why colonization of Slavic Studies has occurred and why decolonization is urgently needed. Without the resistance of Ukrainians to Russian aggression it might never have had a chance to begin. The Ukrainian-Russian war turned upside down the standard narrative about Russia as taught at American and European universities. Many books have been invalidated by the conflict that seemed to come from nowhere. Now this resistance has to be translated into scholarly language and scholarly interpretations.

As stated above, the number of Soviet sympathizers among those teaching Russian subjects has been substantially reduced by political changes and by the retirement of those who taught Russian/Soviet subjects in the 1970s and 1980s. Does that mean that the problems of Slavic Studies have disappeared? Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko’s answer to this question is an emphatic “no.” The problem with Russia is Russia, she bluntly stated in a recent article,[6] thus challenging the view that the only problem the West has had with Russia was rooted in Soviet ideology; otherwise, Russia is just another European nation state. Zabuzhko continued to break the taboos by reminding her readers that in the 1990s, when Chechnya was fighting for independence from Russia, Moscow’s answer was ferocious and barbaric. Russia succeeded by carpet-bombing Groznyi. Why was Moscow so unwilling to let Chechnya go while allowing the so-called “union” republics gain at least nominal sovereignty? Because Chechnya was not a union republic but an “autonomous” republic within the Russian Federation; in other words, it was declared by Russians to be a part of Russia. And woe to those who dared oppose Russia’s territorial interests:

One intellectual holdover from the imperialistic 19th century is the idea that preserving the Russian empire would be less catastrophic, in terms of humanitarian consequences, than recognizing the right to life of dozens of peoples whose lot under Moscow’s rule was never anything other than dogged survival, under the threat of extinction. This prejudice helped the empire to survive twice in the 20th century, in 1921 and in 1991. It is high time to rethink it.[7]

After the fall of the USSR, the prevailing academic and popular view has been that the Russian Federation is a nation state (with minorities, of course, as most other nation states in Europe); that Chechnya or Sakha or Buryatia or Dagestan are legitimate provinces of Russia; that Belarus and Ukraine speak a Russian dialect; and that Russia is a civilizing force in the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The histories and ethnicities of these “stans” were on their way out, while “real” culture and history had their center and reference point in Moscow. Those who specialized in literature knew that only the literature written in Russian was worth paying attention to, because Russian was a lingua franca in all those territories. Didn’t Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Anatolii Rybakov write of non-Russian territories as if they were Russia? As Artem & Iuliia Shajpov put it, the programs of study created by Russoscentric teachers “inevitably framed the region through a Moscow-centric lens”[8].

Thus, even as the word “Soviet” ceased to appear in the titles of books and in the vocabulary of specialists in contemporary Russia, the Moscow-centric framing remained, effectively conflating Russia with all the territories Russia has conquered and downplaying the varied cultures and national identities of non-Russian swathes of the Russian Federation, as well as of non-Germanic Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and the Baltic area.

The Szajpovs suggest removing the word “Eurasian” from the vocabulary of Slavists because of its classically colonialist overtones, and instead introducing Belarusian Studies, Kazakh Studies, or Sacha Studies. Easier said than done. They overlook understandably personal interest of those who dispense this Russocentric knowledge to students. How do you deal with a distinguished émigré who for 30 years has been making students believe that countries like Czech Republic or Estonia really are “Eurasian” rather than European? You cannot fire him: he has tenure. How do you deal with the dozens of former students of such émigrés who internalized the Russian colonial narrative and have been passing it on to new generations of students? In 2010, Oxford University Press put out the eighth edition of Nicholas Riasanovsky’s History of Russia, which is a prime example of colonialist interpretation of the conquests of territories east, west, north, and south of ethnic Russia. This book has been standard fare in teaching Russian and “Eurasian” history for decades. It has distributed “imperial knowledge” to thousands of students. To dislodge its mispresentations will take many years. Merely removing such words as “Eurasia” from the names of various institutes and centers will not be enough. As I was watching political events unfold this past year, I realized that a repudiation of books such as Riasanovsky’s was being written before my eyes. It was written in blood and suffering of the Ukrainians. It took a real war and the spilling of blood to stimulate a second look at Russian studies in America and create hope that they can be restructured.

Why not leave Russian studies alone and introduce more non-Russian studies? For two reasons. First, Russian studies are distended beyond measure. A Department or Chair of Russian should not be put side by side with a Department of English — and yet it has been, at many universities. Yes, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are giants, but if you omit these two, the pickings are limited. Do we really need another book on Pushkin’s poetics or an inquiry about the first translation of Shakespeare into Russian? Do we need to make students read the semi-literate doodles of Ivan the Terrible to Kurbsky? Yet topics like these are subjects of scholarly works for lack of a better alternative. The second reason to shrink personnel teaching Russian literature is arithmetic. If you introduce something new, something else must go to leave room for new subjects. The only realistic way to promote non-Russian Slavic Studies is to reduce Russian Studies.

British writer Edward Lukas came up with a list of suggested changes that should precede such modifications. To start with, “close all Russian consulates and business centers. All we need is the modestly equipped embassies.”[9] Russia Today should not receive license to broadcast in free countries. Americans and Europeans should resign from the various boards of directors of Russian banks and other income-producing enterprises: such positions are ways of bribing Westerners so that Russian interests in the West are promoted. Entities like “Centers for Russian, East European, & Eurasian Studies” should be reexamined and renamed. Lukas knows of course that he has assembled a radical list, but he also knows that unless radicalism is on offer, few transformations will occur. In his view, Moscow has been an identity thief masquerading as the sole inheritor of the Kievan tradition. Yes, it did absorb some of this tradition, but it was a distorted and fragmented borrowing.

An important aspect of decolonization is the rereading of Russian literature from the standpoint of its promotion of colonialist views. While working in this and related areas, I noted a singular lack of interest, on the part of the “classical” anticolonialists such as Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, or Gayatri Spivak, in attaching to Russian literature a colonialist label. Not only the USSR but also the Russian Federation incurred no wrath of prominent supporters of decolonization whose brilliant rereadings of Western literatures are universally known. The theorists of decolonization pointed out the crimes and misconduct of Western Europeans in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, but they have been silent about the history of Russian violence in Asia and Europe. Why? Because both Soviet and tsarist Russia supported revolts against Western empires and Western cultures, and it would have been awkward to point out that Russia too was a colonial power. This is the principal reason why the most dedicated anti-colonial personalities worldwide seldom mention Russia as a colonial culprit. Have you ever heard Nelson Mandela condemn the Russian ways of keeping the subjugated nations down? The Republic of South Africa and several other African countries have not condemned Russian attack on Ukraine. After the USSR collapsed, the networks funneling funds to “liberation movements” in Asia and Africa were weakened but did not disappear. Whether white, red, or colorless, Russian imperialism turned out to be incredibly tenacious; it is impervious to regime changes and political trends, and it has found ways to remain invisible to so many domestic and foreign readers. No matter the name of a current incarnation of the Russian state, it adheres to its imperial directive consisting of continuous expansion,[10] and it silences those who might alert the world to the iniquities of such expansion. Russian literature absorbed this feature of the Russian state, but scholars remained blind to it — until recently.

I would like to pause for a while over one example of how Russian policy makers have striven to mislead public opinion worldwide by suppressing access to historical records that should have been opened for scholarly inspection. The example extends over generations. It involves tsarist Russia, communist Russia, and the postcommunist Russian Federation. It testifies to the correctness of Oksana Zabuzhko’s statement that “the problem with Russia is Russia.” Polish scholar Henryk Głębocki was researching world press reports about the 1863 Polish rising. At that time, a large chunk of Polish territory was in Russian hands. It was a poorly prepared rising of the Polish educated classes who revolted against the lack of freedom and government interference in private lives of citizens. The rising failed and Tsar Alexander II punished the participants and their families by confiscating all properties (land and homesteads) of those suspected of participation. Many Catholic monasteries and convents were also closed down and their property confiscated. Several thousand men were sent to Siberia to work in the mines or otherwise support the Russian empire by their slave labor. Dozens were executed. The January 1863 rising cost the Polish nation its best sons and daughters, in addition to being an economic disaster for the Polish population. The social fabric of Russian-occupied part of Poland was torn beyond repair.

The way the tsarist government treated Poles was likely to arouse sympathy abroad if information about the aftermath reached Europe. To his amazement, Professor Głębocki found that a number of articles published in Western Europe presented the rising in an entirely different way. According to these articles, Poland was a backward and anarchistic country that revolted against attempts to modernize it. It posed danger to the European order. It was Catholic and reactionary, whereas Russia was enlightened and modern. Tsar Alexander II was the Russian equivalent of Abraham Lincoln, and his goal was to free peasants from feudal slavery to Polish nobles. Just as American slaves were liberated by Abraham Lincoln, so were the Eastern European peasants liberated by the tsar, and that is why the Polish nobility started the rebellion.

Głębocki was taken aback by these fraudulent narratives and the influence they exerted on Western European public opinion. He decided to probe the issue. His research took him to the nineteenth-century Russian archives. He wanted to learn the names of those writers and journalists who published anonymous articles smearing the Polish rising and glorifying Russia. To his amazement, he was told that the names of these individuals remain a state secret.[11] After six generations and 150 years! This unexpected proof of Russian duplicity shows how strongly the colonial mentality has been imbedded in Russian policy. The Russian empire disbursed considerable financial resources on generating mendacious narratives meant to create international approval of Russia’s territorial conquests and universal dislike of nations Russia attempted to “civilize.” Some of those whom the Russian government paid to smear Poland and Ukraine were well known and influential.[12] While the twentieth-century liberation of Central and Eastern Europe weakened these narratives, Ukrainians and Poles are still victims of hostile propaganda Russia has disseminated around the world. Decolonization of Slavic studies has to deal with such issues, in addition to adding Ukrainian, Polish, Belarusian literature and history to the curriculum. Many standard interpretations of Russian policy and Russian literature have to change if a more balanced perspective on Russian role in history and culture is to emerge.

It is important not to confuse decolonization of Slavic Studies with replacing them by Empire Studies. Genuine decolonization involves a radical ability to look at causality not in ways suggested by the colonizers but according to perceptions of the colonized. There exists a slate of books written as if Russians were just like the British, bringing European customs while robbing the conquered territories of material goods.[13] Yet Russian colonialism was not a branch of the Western European variety: the two differed widely in strategies and instruments used, and in the final results. While Russians tried to convince West European governments that their mission in Asia and the Caucasus was a civilizing one, they only persuaded those who wished to be persuaded. A rereading of Russian literature has to take these issues into account.

For decolonization to be genuine and successful, the colonized themselves have to develop a discourse, rather than being served patterns of discourse by ideologues from abroad. Such was the course of events in the Western world. It was not by accident that the first person who sketched out the methodology of decolonization came from the Middle East, and the first person who conveyed the psychological harm wrought out by colonialism, came from the island of Martinique. Similarly, we should respectfully accept the methodology that Ukrainians and Chechens and Poles are working out with regard to their decolonization, rather than patronizingly impose on them the critical tools we find attractive. Decolonization involves identity politics which has had a bad press of late. It involves nationhood and group identity, and both terms have been scorned by many contemporary philosophers and ideologues. Yet the opposite wave should also be mentioned. Yoram Hazony’s The Virtue of Nationalism (2018) makes a case for the concept of nationhood as an organizing principle for humanity.[14] Margaret Canovan’s Nationhood and Political Theory defends nationhood in a remarkable way.[15] I have argued that the only known and tested way to organize societies is by allowing them to congeal around the concept of common culture, history, and values — and this is what nationhood is.[16] Virtually all theorists of colonialism admit that anti-colonial movements developed around the concept of nationhood. We observe a surge of national pride in Ukrainians fighting the Muscovites, just as we saw it in the Chechens fighting Russian aggression in the 1990s. Such pride is a sine qua non of anti-colonial movements. Condemning decolonization movements as “nationalistic” means denying the right to liberty and imposing a dismissive label on what for the colonized people is a life-or-death struggle. Yet many scholars resist the idea of decolonization because it is strongly connected to the idea of national sovereignty.

One should not trivialize the impairment imposed on the conquered by the colonizing nation. While acknowledging colonization, some scholars try to minimize the profound trauma it has foisted on national cultures.[17] These scholars propose to concentrate on a less weighty topic, namely, dependency on foreign political and cultural pressure. They prefer to use the word “dependency” when speaking of censorship and physical violence against representatives of a particular nation. They wish to use the word “dependency” in situations where writers have been intimidated and sometimes killed just for not being Russian.[18] In my view, it is an act of great timidity to try to contain within the word “dependency” the harm done to individuals and cultures.[19] As the Buryat scholar Botakoz Kassembekova stated, there is enough material documenting Russian colonialism to make discussions about “whether” rather than “how” redundant.[20] Emily Couch has noted that the war in Ukraine mobilized the awareness of other nations conquered by Russia that they have been in fact colonized.[21]

As it often happens when a new scholarly direction is being considered, attempts to hijack decolonization and use it to promote social restructuring have also occurred. Even though gender inequality has been less of a problem in non-Germanic Central Europe (and Eastern Europe) than in the West,[22] there have been attempts to direct decolonization away from getting rid of foreign rule and creating conditions for democracy, to restructuring society according to theories that have little to do with colonialism. The last time such an experiment has been attempted was under communism, with results generally known. As the number of those who approve of decolonization grows, so does the number of those who would like to use it to advance their own ideological agendas. Changing the meaning of words was a specialty of the communist system and it did not work. Using decolonization as a weapon to change society is a mistake.

Talking or writing about colonialism touches upon one of the greatest problems humanity has faced: the obsession with power and the unending acts of violence perpetrated by the stronger on the weaker. It is partly because of that problem that humanity has organized itself into national groups. Being a member of the group, sharing the same language, history, and culture, and having the same heroes, is an insurance policy against being attacked, destroyed, overcome, harmed, enslaved. I emphasize that nationhood is not racist: it is not skin color but a common culture that makes individuals into members of the same nation. It is important not to divert decolonization onto paths that have nothing to do with that sense of admiration and peace that belonging to a particular culture bestows on an individual. I therefore disagree with those who attempt to usher in what I call an epistemological decolonization, or changing the meaning of words so that decolonization does not mean restoring liberty to nations and sovereignty to territories, but rather ushering in social changes such as a new sexual morality or a return to communism — which as we know from practice cannot exist without a Gulag.[23] Nor is it appropriate, in my view, to treat the drive toward decolonization as an attempt by captive nations to copycat America’s liberalism, as Thomas Friedman seems to suggest.[24] No, Mr. Friedman, Ukrainians are not fighting for a “liberal order.” They are fighting for liberty to decide what political system they want for their land. They cannot make that decision while being ruled by Moscow. It is likely that they will choose liberalism, but for that to happen they need to free their nation from Moscow’s supervision. I am strongly against the proposition to liquidate nationhood and liberty as key issues in decolonizing societies and rereading literary works, especially that practice shows that the colonizing policy of Moscow has been mostly directed at the nationhood of the conquered lands.[25] Significantly, Sergiy Plochiy, professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard, compared Ukraine’s war with Russia to Americans becoming a nation after the Civil War.[26]

In theory, political and social decolonization should precede a scholarly one. This, however, will be difficult to achieve. Evgeniia Baltatarova, a journalist and human rights activist from Ulan-Ude, brought to light a seldom-raised issue of “subaltern exhaustion” that often makes decolonizing efforts appear fruitless. Sometimes it takes too much time and effort to oppose the empire in conditions that require full engagement in survivorship. In the Russian Federation, imperial exploitation produced a mindset where “many people live in their small Buryat world. This is the logic of the colony: it is better not to interfere in all these great upheavals. ‘White great people’ will decide for us.”[27] Similarly, timid passivity sometimes characterizes teachers of non-Russian Slavic languages and literatures, placed at the end of the pecking order in their respective departments. These realities of Russian colonialism have to be taken into account as one looks critically at Russian literature and Russian political writings.

What can be done? The first step is to introduce non-Russian Slavic cultures and histories into university syllabi. Then introduce subaltern interpretations of these histories and cultures within the formerly colonized sphere. This should begin to correct the mistakes in American and European memory politics.[28] It would also enliven scholarship that in many areas of Slavic Studies seems stagnating. Initiatives should be undertaken to invite Western readers to reach for books written by non-Russian Slavs. Exhibits, concerts, exchanges, presence in the media, popular TV programs. France has already taken steps to make Ukrainian culture in particular more prominent. They include creation of a fund to support Ukrainian cinema, translations from Ukrainian literature, and exhibits of Ukrainian art.[29] Student exchanges and fellowship programs for non-Russian Slavic students should be invigorated. The goal of these activities should be the removal of Russian-made lenses through which American and European students of Russia, of non-Germanic Central Europe, and of Eastern Europe have been looking at Slavic history and Slavic lands. It is my ardent hope that the Slavic profession will rise up to the task.

In an essay titled “The Artist as Critic,” Oscar Wilde famously quipped: “An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.” Decolonization of Slavic Studies is such an idea. It is new, it is dangerously unsettling for many, and it still wobbles on the rails of scholarship, being in danger of becoming prey to various contemporary ideologies. “Imperial knowledge” is still firmly rooted in the Slavic profession. Yet discoveries can be made when literature, any literature, is subjected to a decolonizing gaze. For both these reasons — advancing scholarship and helping nations gain liberty they need to develop — decolonization of Slavic Studies is a worthy goal to pursue.

[1] Steven Mintz, “Debunking U.S. History: Exposing and bulldozing myths is not enough,” Inside Higher Education, January 25, 2023, <https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/debunking-us-history >.

[2] “Is Academic Scholarship Stagnating?” Inside Higher Education, 26 January 2023, <https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/academic-scholarship-stagnating-0 >.

[3] ASEEES NewsNet, vol 63, no. 2 (March 2023).

[4] Roger Cohen, “War in Ukraine Has Changed Europe Forever” NYT, 26 February 2023, <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/26/world/europe/ukraine-russia-war.html >.

[5] Ewa Thompson, “Slavic but not Russian: Invisible and Mute”, Porównania, vol. 16 (2015), p. 15.

[6] Oksana Zabuzhko, “The Problem with Russia is Russia,” New York Times, 20 February 2023.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Artem Shajpov and Iuliia Shajpova, “It is high time to decolonize Western Russian Studies,” Foreign Policy, February 11, 2023.

[9] Edward Lucas, „Dziesięć punktów, aby powstrzymać Putina,” Wszystko Co Najważniejsze, no. 39 (24 February 2022), <https://wszystkoconajwazniejsze.pl/edward-lucas-dziesiec-punktow-by-powstrzymac-putina.html>.

[10] Casey Michel, „Decolonize Russia,” The Atlantic, 21 February 2023, <https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/05/russia-putin-colonization-ukraine-chechnya/639428/>; “Russia’s Colonized Populations Can Do Without All the ‘Westsplaining’,” New Republic, 6 December 2022, <https://newrepublic.com/article/169481/russia-ukraine-colonies-future-westsplaining#main>. Also Susan Smith-Peter, “What Do Scholars of Russia Owe Ukraine?” Paper, NYU Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, 1 April 2022, <https://jordanrussiacenter.org/news/what-do-scholars-of-russia-owe-ukraine-today/#.ZAeyfOzMIUE>.

[11] „Nawet po 200 latach wykazy redaktorów zagranicznej prasy na Zachodzie, subsydiowanych przez rosyjskie ambasady, wciąż nie były udostępniane badaczom (czego mogłem sam doświadczyć w archiwach w Moskwie).” Henryk Głębocki, “Rosyjska propaganda przeciwko Polsce na Zachodzie zaczęła się już w epoce powstania styczniowego,” Wszystko Co Najważniejsze, February 25, 2023; < https://wszystkoconajwazniejsze.pl/prof-henryk-glebocki-rosyjska-propaganda-przeciwko-polsce/>; English version, “Russian anti-Polish propaganda in the West during the January Uprising,” Wszystko Co Najważniejsze, no. 465 (February 2023), <https://wszystkoconajwazniejsze.pl/prof-henryk-glebocki-the-most-powerful-weapon-of-our-times-russian-anti-polish-propaganda-in-the-west-during-the-january-uprising/>; „Russia Expels Polish Historian Without Explanation,” RFE/RL, November 27, 2017, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-expels-polish-historian-glebocki/28880337.html.

[12] Among the most influential was Voltaire whose writings in defense of the partitions of Poland penetrated eighteenth-century political discourse in Europe. Romain Cornut, Voltaire et La Pologne, (Bruxelles: Bureau Central de la Revue de Bruxelles, 1846) ; Remigiusz Forycki, “Wolter i jego rosyjska fatamorgana,” Teologia Polityczna, November 18, 2019, <https://teologiapolityczna.pl/remigiusz-forycki-wolter-i-jego-rosyjska-fatamorgana-1>.

[13] Typical here is Susan Layton’s Russsian Literature and Empire (Cambridge Univ Press, 1994) that sees the lengthy and genocidal conquest of the Caucasus as a “bloody conquest in the name of European civilization” (p. 109). Unlike the British who left the legacy of European democracy in countries such as India, Russians left nothing worth preserving.

[14] Yoram Hazony, The Virtue of Nationalism (New York: Basic Books, 2018).

[15] Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 1996.

[16] Ewa Thompson, “Can Democracy Survive without Nationalism? American Thinker, 1 September 2019, https://www.americanthinker.com/articles/2019/09/can_democracy_survive_without_nationalism.html.

[17] Ewa Thompson, “Sarmatyzm i postkolonializm,” Europa, 137/2006 (November 18), p. 11, <https://wiadomosci.dziennik.pl/wydarzenia/artykuly/193060,sarmatyzm-i-postkolonializm.html>.

[18] Ewa Thompson, Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000), pp. 179-180.

[19] Foremost in propagating the “dependency” in Poland theory is Hanna Gosk. See her “Identity-Formative Aspects of Polish Postdependency Studies,” translated by Jan Szelągiewicz, Teksty Drugie, vol. 1 (2014), pp. 235-247. The “dependency theory” was borrowed from sociology: Tomasz Zarycki, “From Wallerstein to Rothschild: The Sudden Disappearance of the Polish School of Dependency Theory After 1989 as a Manifestation of Deeper Transformations in the Global Field of Social Science,” Journal of World-Systems Research 29(1), March 2023, 149-173, <https://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/jwsr/article/view/1135>.

[20] Botakoz Kassembekova and Erica Marat, “Time to Question Russian Imperial Innocence,” Ponars Eurasia, 22 April 2022, < https://www.ponarseurasia.org/time-to-question-russias-imperial-innocence>.

[21] Emily Couch, “Is the Ukraine War an Anti-Colonial Struggle? Fellow victims of Russian imperialism are finding solidarity with Kyiv”, Foreign Policy, 23 March 2023.

[22] Statistics show that in 2021, women in non-Germanic Central Europe and Eastern Europe were more likely to be scientists and engineers than women in Western Europe. It has also been statistically demonstrated that violence against women is less pronounced in non-Germanic Central Europe than in Western Europe. <ec.europa.eu/Eurostat>. It was not an accident that Maria Curie-Skłodowska was Polish-born.

[23] I perceive these tendencies in the oral presentation by Marina Mogilner, in the zoom webinar “Decolonization: Why Does It Matter?” 3 February 2023, <https://daviscenter.fas.harvard.edu/events/decolonization-why-does-it-matter>. Significantly, the two remaining participants in the webinar saw decolonization as a process of getting rid of Russian interference in the lives of non-Russian neighboring nations: Svitlana Biedarieva spoke about appropriation of Ukrainian art by Russians, while Epp Annus presented an overview of Russian colonialism.

[24] Thomas L. Friedman, “Year Two of the Ukraine War Is Going to Get Scary,” New York Times, 5 February 2023.

[25] Among the attempts to destroy nationhood in Ukraine is the Valuev Circular of 1863, stating that “a separate Little Russian language [as they used to call Ukrainian then] never existed, does not exist, and shall not exist, and their tongue used by commoners is nothing but Russian corrupted by the influence of Poland;” and the Ems Ukaz which completely prohibited the use of Ukrainian language in open print in 1876. Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev, “Not all criticism is Russophobic: On decolonial approach to Russian culture”, Dispatches from Ukraine: Tactical Media Reflections and Responses, edited by Maria van der Togt (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2022), pp. 68-73,<https://mediarep.org/bitstream/handle/doc/20439/TOD_44_Togt_ea_2022_Dispatches-From-Ukraine_.pdf?sequence=-1>.

[26] Sergiy Plochiy, interview, PBS NewsHour, 24 February 2022.

[27] Quoted from Svitlana Matvienko, “Dispatches from the Place of Imminence,” Institute of Network Cultures, 10 May 9 – 29, 2022, <https://networkcultures.org/blog/2022/05/31/dispatches-from-the-place-of-imminence-part-10/>.

[28] Maria Mälksoo, “The Memory Politics of Becoming European: The East European Subalterns and the Collective Memory of Europe,” European Journal of International Relations (2009), pp. 653-680.

[29] “France joins Ukraine in the battle for cultural liberty against Russian aggression”, Russia World, February 26, 2023, < https://russiavsworld.org/france-joins-ukraine-in-the-battle-for-cultural-liberty-against-russian-aggression/>.

Read also

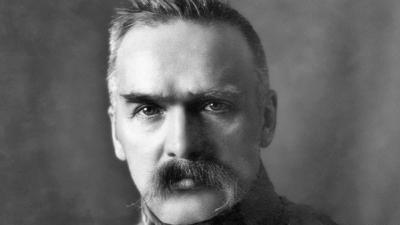

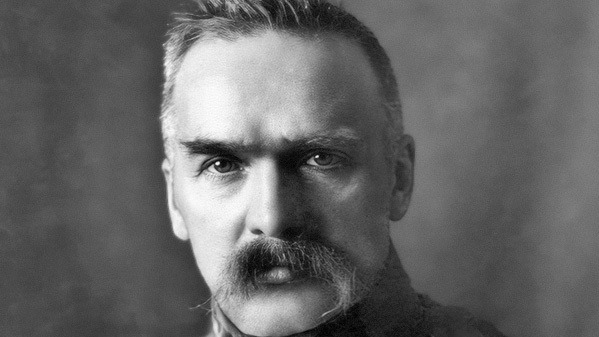

Book review: Jozef Pilsudski: Founding Father of Modern Poland

Written in a crisp and matter-of-fact style, with copious footnotes legitimizing it as an academic work, this volume can compete for the best Piłsudski biography to-date.

Ewa Thompson

Can We Communicate? On Epistemological Incompatibilities in Contemporary Academic Discourse

In 1990 the American philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre published Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry: Encyclopedia, Genealogy, Tradition. The last chapter of this book is titled “Reconceiving the university and the lecture,” and it ends with a proposition: in academic discourse we should “introduce” ourselves before we start speaking.

Comments (0)