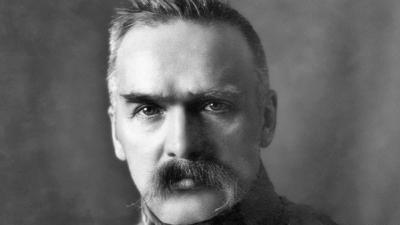

Book review: Jozef Pilsudski: Founding Father of Modern Poland

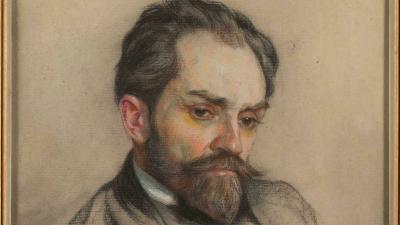

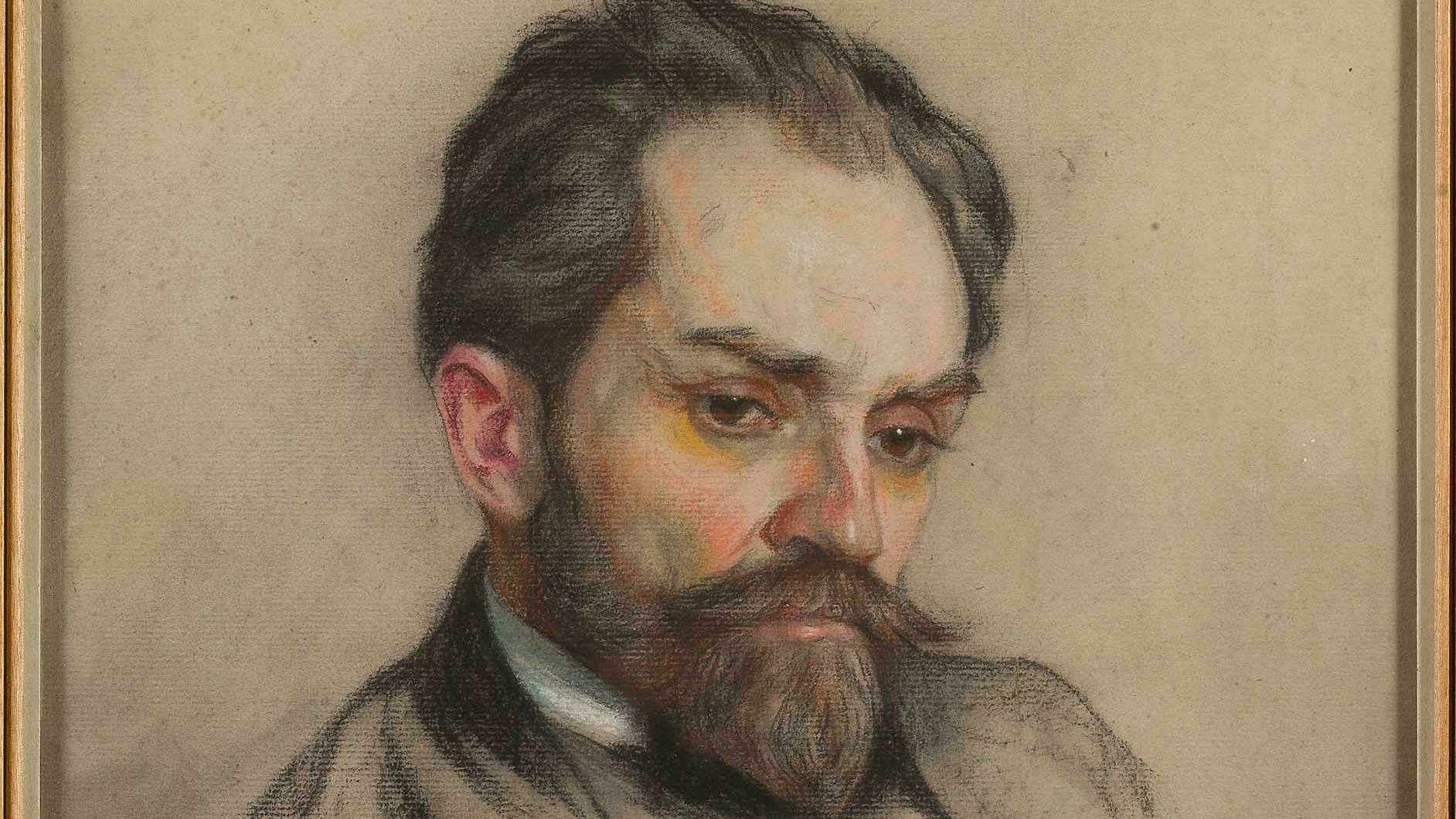

Jozef Pilsudski: Founding Father of Modern Poland, by Joshua D. Zimmerman. Harvard University Press, 2022. x+623 pages. ISBN 9780674984271 (cloth).

Written in a crisp and matter-of-fact style, with copious footnotes legitimizing it as an academic work, this volume can compete for the best Piłsudski biography to-date. It focuses on the Polish statesman’s political and military achievements and failures, rather than on his private life or psychological characteristics. Piłsudski was so devoted to the idea of reviving and modernizing the project once called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with its premodern liberalism and a democratic form of government, that he did not dedicate much time to his own welfare or to the natural human desire to live a successful life on the bosom of a loving family.

What emerges from this narrative is an unsentimental portrait of Piłsudski as a man of exceptional talents, one who knew how to inspire his countrymen and at the same time be able to serve as a military strategist. Piłsudski’s ability to militarily outwit the enemies of Poland many times stronger than the new state-in-the making led to a political miracle: the rebirth of Poland as a sovereign country in the midst of Russian, German, and Austrian disarray after World War 1. Yes, President Woodrow Wilson did help, but without Piłsudski’s Legion the creation of a sovereign state would have been all but impossible. Zimmerman does not say so directly, but the way he structures his book leads to this conclusion.

Piłsudski was born in 1867 in Lithuania, a country with a substantial Polish minority that contributed mightily to Lithuania’s political and cultural profile. This was the golden age of empires in Europe and elsewhere, and both Poland and Lithuania were part of the Russian Empire whose roots were Byzantine and Asian rather than European. Piłsudski’s personality and character were shaped by the fiercely patriotic milieu of the Polish educated classes in Lithuania (and in Poland proper as well), and by the three Romantic poets whose works defined the contours of Polishness in those times: Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, and Zygmunt Krasiński. The way the Russians ran their empire could not but generate resentment in the inheritors of the idea of liberty to whom Piłsudski belonged. As a member of an underground anti-tsarist organization and editor of the underground monthly Robotnik (The Worker), Piłsudski was arrested and sent to eastern Siberia. There he met other expellees from the empire’s western borderlands, among them Bronisław Szwarce and Stanisław Landy, whose socialist views influenced him considerably. The strongest current of anti-tsarist opposition in those years was one that espoused socialist ideas, and Piłsudski joined it. Zimmerman emphasizes the fact that Landry was a Pole of Jewish background. Piłsudski’s spectacular ploy in escaping Russian imprisonment is worth a movie, and so is his breathtaking success in recovering Polish funds on their way to Saint Petersburg, and using them for underground publications and party expenses. Zimmerman dedicates little time to this famous train robbery; it is however remarkably well described by Peter Hetherington in another recent biography of Piłsudski.

An aspect of Piłsudski’s personality that Zimmerman rightly foregrounds has to do with his uncanny ability to predict the outcome of political maneuvers undertaken by Poland’s hostile neighbors. Perhaps the most significant of them was his remark - made after the 1934 signing of the nonaggression treaty with Germany - that it would hold back Germany for four years at most. Indeed, the Anschluss of Sudetenland happened exactly four years later. Piłsudski also predicted the timetable of disintegration of the German and Austrian armies in World War 1, as well as the spectacular defeat of General Samsonov’s army in East Prussia. The most significant foresight was shown during the Polish-Soviet war of 1920, when the Polish leader’s brilliant maneuver of moving his soldiers deep into the rear of the Soviet army and attacking from behind saved Warsaw from General Tukhachevsky’s atrocities and planted the seeds of defeat in the minds of the attacking Soviets. Piłsudski’s ability to predict the outcome of military actions was not a paranormal skill but a product of exceptional intelligence combined with intense study of military history and strategy. Several times in the book Zimmerman mentions Piłsudski’s diligence in studying military strategies.

The author has no doubt that Piłsudski was a committed democrat at heart, as reflected in his writings and efforts to make sure that the laws of independent Poland do not discriminate on the basis of gender, nationality, or religion. Those scholars in the West who write about the Polish leader should not doubt it either. However, through ignorance or malice, the Polish statesman has sometimes been classed together with such dictators as General Franco or Benito Mussolini. Cui bono? The beneficiaries have been Russia and Germany. Zimmerman distances himself from such crude insinuations.

While Piłsudski’s personality dominated the political scene in Poland in the 1920s and early 1930s (he died in 1935), the domination was largely indirect. He refused the presidency of Poland twice. Zimmerman points out that according to the 1921 Constitution, the Polish president had little official power, a circumstance that was partly responsible for Piłsudski’s intervention in 1926. The Marshal (the title he received at the end of World War 1) wanted Poland to have real and not fake elections where several candidates would honestly compete for office. At the beginning of the struggle for sovereign and democratic Poland (Piłsudski regarded both features as indispensable ingredients of a successful state), a great deal of democratic memory of Polish society became law. Thus Polish women received the right to vote in 1918, or as soon as foreign occupation was lifted and prior to the enactment of similar laws in Great Britain (1928) and France (1944). The 1921 Constitution enshrined the postulates of equal rights for every citizen. But right at the beginning of what should have been for the Poles a period of undisturbed triumph and joy, the assassination of the first elected president by a histrionic fanatic took place. The assassin was brought to justice and received death penalty (promptly executed). This event hurt Piłsudski’s deeply. He knew President Naruszewicz and valued his suitability to become the head of state.

Another blow came in 1926 when Piłsudski realized that disagreements between government members were about to cause a paralysis of the state. In a decidedly undemocratic way, he rushed toward Warsaw (he lived in Sulejówek, in a house which the grateful nation bought for him via a nationwide collection of donations at the end of World War 1), followed by the army detachment loyal to him. A brief battle on the streets of Warsaw ensued, Piłsudski won and the Sejm offered him presidency of Poland. He refused, just as he did in 1919. He wanted Poland to be a normal European country, “with liberty and justice for all,” in which presidents are elected after an electoral campaign. But 123 years of subjugation to the lawless rulers of empires made Poles unable to smoothly sail through the first “water locks” of independence. The conditions of incessant threat from west and east contributed to the breakdown of the Polish political system. After the resignation of Prime Minister Wincenty Witos and his cabinet, a new prime minister was appointed. Ignacy Mościcki, a chemistry professor and a socialist, won the presidency of the republic. Piłsudski accepted the post of defense minister.

Zimmerman points out that after the arrest of opposition leaders, a communist publication called Piłsudski “a fascist dictator” (404). However, “notably absent was any mention of Centrolew’s resolution demanding the dissolution of the Piłsudski government by force” (433). A call to violence issued by the left side of the political spectrum did not result in accusations of fascism or dictatorship, whereas anti-Piłsudski slander stuck. Zimmerman mentions the fact that of the 64 persons arrested, 63 stood as candidates in the 1930 elections. An eerie similarity with the second decade of the twenty-first century: Poland under PiS is declared undemocratic by the left-leaning and foreign-owned Polish mass media, and the calls of the opposition to remove the legitimately elected government by force have not generated a wave of criticism in the West.

In spite of his refusal to step into the shoes of a dictator, Piłsudski became an object of hate and slander for the left wing press in Europe, as well as for the small percentage of Poles who were communists. The negative label easily made it to the books of respectable historians in the West, including American academia. Interestingly, both Jewish and German minorities supported the 1926 coup (408); the only major group opposed was the National Democrats, or the right wing. To his credit, Zimmerman emphasizes the difference between dictatorship and Piłsudski’s role in Poland, and he defends the Marshal from accusations of fascism. He also notes shrewdly that after the 1926 coup the Marshal visibly aged and never regained the enthusiasm with which he participated in the inauguration of the Polish Republic.

Piłsudski continued to participate in Poland’s political life in the late 1920s and early 1930s. His foresight told him that horrible times were ahead, while he could do nothing to prevent them from coming. The last years of his life were marked by increasing pessimism. While great leaders are usually rewarded by distinguished and secure retirement, Piłsudski died prematurely at 68 years of age. The nation honored him by a spectacular funeral attended by hundreds of thousands of citizens. He was, and is, a model for many Poles who value sovereignty and the political ideas born during the four hundred years of the existence of the “Commonwealth of Four Nations.”

Zimmerman’s book should help correct the primitive image of the Second Republic as a country where fascist dictatorship prevailed in the interwar period. Piłsudski was not only an extraordinarily talented man whose military skills saved Europe from the Soviet invasion in 1920, but also a person of remarkable honesty who worked all his life to assure that Poland is a decent country for all her citizens. He succeeded only partially, but then, given the situation of Poland in the 1920s, total success was out of reach.

Western democracies are so secure in their statehood that their citizens do not reflect on the possibility of that statehood being in danger and their nation becoming part of a hostile empire. Would a study of the Polish situation make them reexamine their assessment of Poland after 1926, i.e., of Poland breaking the democratic rules, rewriting the constitution and rearranging the government? Can a country’s leaders forgo the rules of democracy in order to save sovereignty? Piłsudski answered this question as best he could. History has proved him right. Sovereignty is a sine qua non condition of a successful state. Zimmerman calls Piłsudski „enigmatic” (20). Possibly, all great leaders appear to be enigmatic to the world outside.

The book is not without flaws. For starters, I would like to alert the readers to the author’s (or editor’s) decision not to use Polish diacritical marks in spelling Józef Piłsudski’s name. The absence of diacritical marks facilitates the absorption of a foreign name by the presumed majority of readers unfamiliar with the Polish language. However, it also introduces imprecision to the knowledge of Piłsudski. It occasionally happens that the Polish leader’s name appears in the text side by side with another Polish word replete with diacritical marks. This looks odd.

Speaking of Polish words in the text: whoever did the editing of them did a very poor job. A large number of them are misspelled: “Slowaki” instead of “Słowacki” (170), “Podlaski” instead of “Podlaska” (360), “Polskei” instead of “Polskiej” (211), “Ludwig “ instead of “Ludwik” (457), “Wojskowy” instead of “Wojskowych” (213), and many others.

While Zimmerman is wonderfully objective in describing the complicated network of interests in non-Germanic Central Europe, he does not mention two factors that played a major role in crafting the reputation of the territories in question. The first is a relative numerosity of the Jewish population in the area of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Owing to Poland‘s “open door” policy toward Jews in the Middle Ages, territories that once belonged to Poland had more Ashkenazi Jewish inhabitants than the remainder of Europe. This has been a crucial aspect of Polish-Jewish relations in times of war, poverty, and uncertainty. There have been more opportunities for Polish-Jewish encounters (including hostile encounters) in Poland than in all other European countries taken together. In the Second Republic, one in ten citizens was Jewish, as compared to some other countries where one in fifty was Jewish. Furthermore, during Piłsudski’s lifetime, a hefty percentage of Polish Jews actively worked against the reconstitution of the Polish state (to mention only Rosa Luxemburg and Adam Michnik’s father Ozjasz Szechter, a ranking member of the Communist Party of Western Ukraine) This last factor worked toward developing a suspicion with which a part of Polish society viewed their fellow citizens of Jewish background. Zimmerman is a Professor of Holocaust Studies and he should have acknowledged the weight of these realities on political developments in non-Germanic Central Europe.

Finally, I wish Zimmerman paid more attention to the financial aspect of maintaining all those underground organizations, meetings, and periodicals starting with Piłsudski’s Robotnik. Yes, there was the train robbery at Bezdany, but this was a one-of-a-kind event that could not have supported the underground over decades. The first mention of the sources of funds appears on p. 145, where we learn that the funds came from London. Who gave the money and why? Then there is a mention on p. 179 that Piłsudski managed to obtain some funds from the Japanese government. Surely there must have been some substantial sources of funds apart from these occasional windfalls and modest membership fees of the people directly involved.

Read also

Can We Communicate? On Epistemological Incompatibilities in Contemporary Academic Discourse

In 1990 the American philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre published Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry: Encyclopedia, Genealogy, Tradition. The last chapter of this book is titled “Reconceiving the university and the lecture,” and it ends with a proposition: in academic discourse we should “introduce” ourselves before we start speaking.

Ewa Thompson

On Decolonizing Slavic Studies in Europe and America

“War has uncontrollable consequences”, noted historian Steven Mintz in Inside Higher Education in January 2023.[1] Shortly afterwards in the same journal, Mintz argued that American academic scholarship is stagnating.[2]

Comments (0)