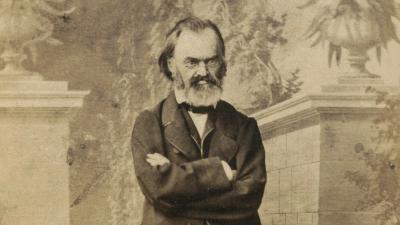

If the philosopher’s victory in the struggle against inexorable time were to be measured by the number of scholarly studies devoted to him at any given time, it would have to be admitted that more than two hundred years after his birth, August Cieszkowski is winning in this struggle.

The list of authors who have made significant contributions to the study of Cieszkowski’s philosophy and religiousness over the past 25 years would certainly include Andrzej Wawrzynowicz, Wiesława Sajdek, Marek Nikodem Jakubowski, Grzegorz Kubski, Piotr Bartula, Stanisław Pieróg, Barbara Markiewicz, Michał Łuczewski or Paweł Rojek. If this list (admittedly incomplete, if only because authors of an older generation, such as Andrzej Walicki or Jan Garewicz, deserve mention) were to be compared with a similar list of authors of publications devoted to Bronisław Trentowski or Maurycy Mochnacki, not to mention others, such as Karol Libelt, Edward Dembowski or Józef Kremer, then the thesis posed at the outset would leave no room for doubt: Cieszkowski is perhaps the only Polish philosopher of the Romantic era who continues to focus the attention of a wider circle of scholars (I omit, of course, the interest with which the philosophical strands of the poets’ work are still studied, including especially Mickiewicz’s Paris lectures). Moreover, one should not forget that in recent years the author of Our Father has also become the patron of a foundation that publishes one of the most important philosophical journals, “Kronos”.

This relatively great interest in Cieszkowski’s philosophy stems from the topicality of the problematic contexts into which he fitted with his two most important works – Prolegomena do historiozofii [Prolegomena to a Historiosophy] and Ojcze nasz [Our Father]. The problems of the third of his major philosophical works, Bóg i palingeneza [God and palingenesis], may seem less relevant today, which is why few more extensive studies of him have been written. It is worth remembering that among Cieszkowski’s twentieth-century readers, we will also find quite a number of foreign philosophers and scholars. Perhaps the most internationally respected of those influenced by the Polish philosopher in the twentieth century is Nikolai Berdyaev. According to Andrzej Walicki, “Polish Romantic messianism attracted his attention as a programme for the nation’s rebirth through a profound modernisation of religious consciousness - a modernisation, we should add, conceived as a revitalisation of religion and thus an alternative to secularisation” [1]. In Berdyaev’s late work, this attention focused precisely on Cieszkowski, “the most noteworthy predecessor of the religion of the Holy Spirit”, who “expressed much more clearly than Solovyov the idea of the religion of the Spirit as ultimate and complete revelation”[2].

At the core of Cieszkowski’s philosophy of religion is a conviction in the two-sided relationship between modernity and Christianity. On the one hand, the philosopher was in no doubt that both the Enlightenment and later (especially those originating in Hegelian leftist circles) critiques of religion are only a “contradictory” and transitional position. Religion will not disappear; it is an enduring element of human history, also needed for the third era of action. The very division between secular and sacred history is an expression of the limited position of the second epoch with its firm separation between the sacred and the profane.

Religion, therefore, does not disappear with progress, but - and this is the other side of the issue - it also does not remain untouched; it develops and transforms. The next epoch sees the taking up of a new position in the field of religion - paracletism, which is supposed to be the fulfilment of Christianity. The relationship of paracletism to Christianity is similar to that between Christianity and the Jewish religion. Cieszkowski directly alludes to Jesus’ words about how he did not come to abolish the Law and the Prophets but to fulfil them (cf. Mt 5:17). The following article is devoted to the presentation of Cieszkowski’s views about these fundamental issues in order to prepare for a theological and political reading of his writings.

Jesus Christ in universal history

In 1838, a young philosophy student, only twenty-four years old, appeared in Berlin with Prolegomena to Historiosophy, written in German. The title “historiosophy” was a new science that was to make it possible not only - as before - to grasp the past speculatively but also to reach the essence of the future[3]. Hegel had not yet come to discover this science - indeed, he had invented the method leading to it, but he had not applied it to the philosophy of history: “The laws of logic, which he himself first revealed, are not reflected with sufficient clarity in his philosophy of history; in a word, Hegel has not arrived at the notion of the organic and ideal totality of history, at its speculative dismemberment, nor at its ultimate architectonics”[4]. The young Pole appeared as one who, consistently applying the Hegelian method to the cognition of history, intended to develop and at the same time transform the position of the author of the Phenomenology of the Spirit.

In his view, history consisted of three epochs - of being, thought and action, constituting the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of the organism of universal history. Cieszkowski’s thought forms a syllogism that can be presented after Stanisław Pieróg. Its first premise states that all human history is an organism, a finite three-phase process of a dialectical nature, consisting of the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The second states that the entire past is enclosed in two phases of historical development, antithetical to each other. The solution is the thesis stating that the historical future is a dialectical synthesis, which thus entails its further characterisation[5].

The progress made in history is also the development of the spirit: “Self-being - self-thought - self-doing are the three primary forms of spirit. Thus, in itself, the spirit is self-being, i.e. an ideal, living individuality that separates itself above all from nature and has its centre in itself. As being-for-itself, the spirit is self-thought, i.e. consciousness, which is the reflection of spirit in general. However, as an entity from itself, the spirit is self-action, i.e. free activity as such, which is the most concrete evolution of spirit. On the other hand, nature can arrive at most at being alongside something else, for something else and out of something else. Self-activity is thus the pinnacle of the possibility of developing ideas and the highest determination that can be made of the absolute”[6]. The most important truth concerning history and its future development, discovered by Cieszkowski in his Prolegomena to Historiosophy, was thus its aiming at action, constituting the reconciliation of being and thought and the realisation of the ideas of beauty and truth in practical life[7].

The division of history into three epochs also led Cieszkowski to distinguish two turning points. The first was linked to the person and work of Jesus Christ: “Before Christianity, namely, there prevailed in history a period of externality and direct objectivity; as for the subjective spirit, it was still at the first level of its development, i.e. at the level of sensuality, while the objective spirit was also in its most direct form: abstract law. Christ, on the other hand, brought to the world the element of interiority, reflection, and subjectivity. He elevated sensuality to the level of inner consciousness, law to the level of morality; hence Christ is the centre of times past, for he alone brought about the radical reform of humankind and turned the great page of universal history”[8]. Christ liberated man from the power of nature and revealed his infinite individual entitlement. It was a liberation that was significant and represented considerable progress, but only half-hearted in the second epoch: “Emerging Christianity only made half of the man free, revealing the equality and infinite entitlement of human souls. But the liberated souls were not at first concerned with the liberation of the body; instead, having despised it, they left it in subjection [...]”[9]. After a period in which man was dominated by an external being, a radical turn took place - freed from the power of the world around him, the man turned to his interiority and contrasted the reality surrounding him with another, higher one: “Just as in antiquity there was only one world, i.e. the present world, while that other world was a mere shadow of this one, and was in fact exposed as a land of shadows, so in the second epoch, on the contrary, that other world gained all the advantage, - there truth, there real and eternal life, while here a mere wandering of shadows; here tormented until time, here inania regna; so this world became a dependent shadow of that one”[10].

However, this position - the “abnegation of the world” characteristic of the second epoch - was not definitive. Nor did it constitute, as we learn in the Our Father, a complete and final interpretation of the teaching of Christ, who not only inaugurated the second epoch but also announced the third. In it, man is to come to the discovery that this world is not opposed to that world but has itself a religious sanction and has been handed down to him by God as an inheritance: “And thou shalt feel thyself in the world, as in a Parental home, and not in any Foreign land, nor exile, in a home which is thy inheritance, even though thou hast not yet firmly taken possession of it for the sake of minority, - after all, it is already thy home, since it is the Father’s, - in a word, thou shalt feel, acknowledge and live in a fulfilling way, not in exile, but in the Father’s land”[11]. The Father referred to in the above quotation is, of course, God Himself, revealed by the Saviour by that very name.

The second epoch, inaugurated by the Saviour, is, therefore, the time of man’s gradual growth into action: the time of knowledge. Because the deed is a post-theoretical practice, it is an action consciously shaping one’s own reality. Historiosophy as the culmination of this cognitive process is thus - Cieszkowski argued in his first philosophical work - situated between intuition and the fulfilment of history. It is that knowledge that humanity needed to assume responsibility consciously and maturely for its own history: “Already this first chapter [of Prolegomena to Historiosophy - T.H.] sufficiently explains why we have called our account of the philosophy of history historiosophy. First of all, we have marked its phenomenological origin by contrasting it with historiopneustia, thus placing it between the intuition and the fulfilment of history, at the turning point where facts are transformed into deeds; this turning point then becomes the theory, the absolute knowledge of history, or, objectively speaking, the wisdom of universal history”[12].

Universal history and the history of salvation

Jesus Christ is thus - Cieszkowski argued both in Prolegomena to Historiosophy and in Our Father - at the centre of history to date. The doctrine he brings not only inaugurates a second, antithetical and therefore one-sided epoch but also foreshadows and directs humanity towards a third, definitive epoch of universal synthesis, or reconciliation of thought and being. “The summary of the Gospel”, containing the revelation of the essence of the future, is the Lord’s Prayer. In Christianity itself, therefore, there are not only transitory elements associated with the second epoch of history but also eternal elements arising from the very nature of Christ’s teaching.

The fact that the already purely speculative and non-theological layer of Cieszkowski’s philosophy naturally opened it up to development towards religious philosophy does not mean that such a development did not constitute a theoretical breakthrough of momentous consequence. The modern philosophy of history, despite its undeniable religious sources, was shaped in clear opposition to the theology of history. Cieszkowski, as early as in Prolegomena to Historiosophy[13], sought to reconcile the philosophical and theological perspectives, and in Our Father went much further, linking general history with the history of religion and, consequently, the history of salvation. The Polish philosopher made the process of the emergence of successive religious formations directly dependent on the progress of salvation, which is also characteristic of the theological view of the relationship between Israel and the Church.

One of the conditions for linking universal history with the history of salvation was, of course, a specific account of the essence of religion itself, which Cieszkowski defined etymologically, deriving it from “ties”. This naturally led to a depiction of the close links between social life and religion, for religion understood in this way, Cieszkowski argued, is realised precisely in people’s fellowship with God and one another, rather than in specific ideas about transcendence proper to the position of the other epoch. It is worth noting, moreover, that in this respect, Cieszkowski’s views are very close to the biblical idea of the covenant as a fundamental fact of religious life and the theology of ancient Israel.

However, let us remember the reciprocal significance of the bridge that Cieszkowski throws between religion and modernity. In this mutual dialogue, religion also develops, and the direction of this change is best demonstrated by the following quotation: “Not, therefore, the blind performance of the rites of the old order (cerimoniae legis), - nor the merely conscious recounting of the divine word of the new order (praedicatio verbi); - not the real sacrificia only, nor the ideal sacramenta only, will continue to constitute the essential worship of God, - but the active cultivation of all the gifts of the Spirit, which God, in His image, has bestowed upon us all, - the self-fulfillment of God’s will, both on earth and in heaven; and through this, the realization on earth of the hitherto ideal Kingdom of God; the assumption and preparation of all men to partake of both the physical and the moral bread of life; - sanctification, no longer to the extent of faith and vain Grace, but to the extent of our own deeds and Merit; the amelioration of the strife within, which has hitherto distracted mankind alike, and thus the world-wide deliverance of mankind from the Power of Evil; - in a word, an active life in God, who is, was and always will be the Holy Spirit, and the life of that Holy Spirit in us as in His members: - this is the extraordinary task of the ages to come. Thus, the epoch of the Father and the epoch of the Son, through the epoch of the Holy Spirit, will be fulfilled”.[14]

The above quotation already introduces one of the most critical strands of Cieszkowski’s religiousness - his conception of salvation. Both the religious philosophy and a kind of “philosophical Christology” of this author are strongly dominated by the historic-redemptive dimension, which is obviously due to the main object of his interest. In the first pages of Our Father, we find one of the most quoted passages from this work, which illustrates well the understanding of salvation proper to Cieszkowski: “The salvation of People and Peoples - of the People and Humanity - today depends on themselves and them alone. - The time of Grace has ended - the time of Merit has come. - Mercy has been accomplished, and Atonement is being made. - The moment of futile gifts has passed - the moment of reckoning has come. - After all the talents given were enough, - let us count what they brought. Woe to the buriers - glory to the earners!”[15]. The reference in this passage to the parable of the talents, which will be used for an almost identical purpose by the aforementioned Nikolai Berdyaev, is characteristic. Of particular relevance to Cieszkowski’s political theology is the idea of developing the gifts of the Spirit, explicitly alluding to the twelfth chapter of I Corinthians. Most important, however, is the conclusion reached by the Polish philosopher - the conviction that in the third epoch, salvation will depend on human action.

There is no doubt that this imminent assumption by humanity of responsibility for its history, according to Cieszkowski, is not a turn against God at all, but an expression of his action towards the world. Already from the Prolegomena to Historiosophy, the reader learned that God’s reign in the world manifests itself in three forms, for the last time as “rationally mediated in the future by the achievement of the ultimate divine goal, i.e. happiness, in the concretely accomplished teleological passage of history”[16]. For Our Father, it is characteristic - corresponding to Cieszkowski’s basic assumptions - to present God’s action towards man as education. In introducing such an idea, the Polish philosopher refers above all to Lessing, but it seems that for a proper grasp of the theological-political dimension of his thought, it is also important to place his considerations in the context of early Christian paideia. In turn, the justification for such a picture of God’s activity towards man is as follows: “It is not, therefore, for a negligible spectacle that God goes - nor for vain agitation for the human race - but for the fulfilment and attainment of the Goal of all the Spirit. – The point is that the sentient, thinking, and free Humanity should come by itself (de facto, de jure et sua sponte) to the desired, conscious, and self-creative Harmony. - For it is under this condition that Spirit is Spirit, that it develops itself, that it is its own Lineage, as we shall immediately recognise. And it is only on this condition that it is capable of attaining Harmony, that it creates it itself; otherwise, if it were somewhere ready to find me, he would seek it in vain - he would only deceive himself”[17].

In this context, it should also be noted that while the time of the liberation of the individual human being was a time of grace which the individual could freely receive, the liberation of humanity as a whole can no longer be based on it, except at the price of recognising it as God’s violence against creation. For the freedom of humanity as a collective subject cannot be presented merely as the freedom to open up to grace since only each individual human being can manifest such a capacity. If therefore, the building of the Kingdom of God on earth were to be framed in terms of the Christian doctrine of grace, this would take place - this is how Cieszkowski might persuade his reader - to the exclusion of freedom. Thus, this transformation of the traditional Christian position is logically dependent on the adoption of a collective subject of salvation - one who can no longer freely accept salvation from outside but must actualise it himself by deed.

Conclusion

Cieszkowski’s religious philosophy - like that of other Polish Romantics - often faced accusations of heresy. The nature of the problems it addresses, however, means that focusing on the “orthodoxy” or “heterodoxy” of its specific solutions does not lead to grasping the essence of the problem at all and is done at a loss - not so much for Cieszkowski himself, of course, as for the reader. The philosopher’s position in the religious field was aptly defined by Andrzej Wawrzynowicz, who noted that “the fundamental aim of Cieszkowski’s Our Father is to derive the ultimate philosophical (or more precisely: historiosophical) consequences from the (evangelical) teaching of Christ, in possible agreement with the official theological line of the Church, or possibly (if necessary) without it”[18]. Although Cieszkowski did not complete his Our Father, he achieved one of his goals, for he developed an approach within which it became possible to apply the data of Revelation to his contemporary socio-political reality. According to Grzegorz Kubski, “the merit of the thinker of Wierzenice is his attempt to find a formula of discourse which, without being occasional journalism, would make it possible to give answers to the present day by means of an exegetically illuminated biblical text. Exegetically illuminated, i.e. not connected to the contemporary issue of the 19th-century reader only by some superficial accommodation, but by reaching what is actually there, if only in the seed, in the words of the hagiographer - here Cieszkowski leaves no doubt - who formulates the word of God”[19]. This, in turn, must have involved a great deal of work, “for it is difficult in the same supposition to apply such biblical terms, which often refer to the condition of the person, and this in the mystical-spiritual aspect of his undoubtedly real existence, to describe this time practical social issues or the position of the whole of humanity even. Modern religious discourse, then, when Socrates of Wierzenice began to write his treatise, had not yet had the experience of specialised language for this. Moreover, it was precisely in this respect (especially regarding social issues) that the Romantic writers were somehow ahead of the official pronouncements of the Church, by its vocation, obliged to apply the word of God to the current situation of people”[20].

The work that Cieszkowski did was needed not only for the Church but also, according to his most profound conviction, for the development of humanity. The fruit of this work was a work that was to testify to the fact that the idea of modernisation not only need not go hand in hand with secularisation but that at some point, it must surpass it, leaving it behind as its only transitional stage. There are probably many reasons that led Cieszkowski to reach out to religion, but one is worth noting. The philosopher sought to popularise historiosophy, which was necessary for the “transition of philosophy into life”. What fascinated him about the Lord’s Prayer was its universality, its almost unlimited scope of influence on all strata of the social structure. For if progress is to be definitive and lead to the building of the Kingdom of God on earth, an egalitarian aspiration must be firmly inscribed in it. Therefore, the indispensable condition for further progress is not only the transcending of secularisation but also the empowerment of all strata of society without exception. For this, in turn, what is needed is not only - as appears in Cieszkowski’s writings - a solution to the “social question” or appropriate education but also a theoretical appreciation of religious language, the only language that bears the mark of universality. According to Cieszkowski, modernisation is an affirmation in which there is no room for negation - progress that will not leave behind a multitude of excluded but will become the real culmination of history. Religion proves to be an indispensable element, the basis for the development of the whole of humanity in this way.

However, one might ask what effect this strategy of transcending secularisation, which can be read from Cieszkowski’s works, had on religion. The paracletism of the Polish philosopher is a religion of public life that replaces faith as central to the Christian understanding of salvation with action grounded in knowledge. It is meant to transcend the limited - in Cieszkowski’s view - perspective on the understanding of salvation, the following formulation of which was given by Saint Paul: If you declare with your mouth, “Jesus is Lord,” and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved. For it is with your heart that you believe and are justified, and it is with your mouth that you profess your faith and are saved” (Rom 10:9-10). The movement between modernity and Christianity is, in Cieszkowski’s view, bilateral - with all its consequences. It is, therefore, not exclusively the case that Cieszkowski argues against the link between modernisation and secularisation. At its points of arrival, his philosophy of religion takes on a distinctly post-religious overtone, which, by the way, is done partly in defiance of the thinker’s initial intentions. Religion is to return to the heights of modernity but as identified with social praxis. The same conviction that made Cieszkowski’s work radically opposed to the paradigm linking secularisation with modernisation had him convinced that Christianity of the second epoch of history would be followed by a new, higher religious position - paracletism as realised Christianity. For this reason, however, religion had to get mired in the affairs of this world and this age for him.

The text in the revised and expanded version presented above was first published in Political Theology Weekly 2019, No. 158 and is available online at: https://teologiapolityczna.pl/tomasz-herbich-alternatywa-sekularyzacji-o-teologii-politycznej-augusta-cieszkowskiego

[1] A. Walicki, Mesjanizm i filozofia narodowa w okresie renesansu filozoficzno-religijnego w Rosji a romantyczny model polski [in:] Idem, Prace wybrane, t. 4: Polska, Rosja, marksizm, Kraków 2011, p. 353.

[2] M. Bierdiajew, Egzystencjalna dialektyka Boga i człowieka, translated by H. Paprocki, Kęty 2004, p. 130.

[3] Cieszkowski firmly emphasized that his goal was to capture only the essence of the future, not its detailed course.: „Here we place the main emphasis on the essence, because only it can, especially in this case, be the subject of philosophy. For the necessary essence can manifest itself in the existence of an infinite number of cases, which must always remain arbitrary, and therefore cannot be foreseen in detail, and yet must constantly manifest themselves as a worthy and adequate refuge for the inner and general. [...] As far as the future is concerned, however, we can only fathom the essence of progress, for the possibilities of realization are so rich, the freedom and fullness of spirit so great that we are always in danger of reality in its details either surpassing or at least failing our expectations” (A. Cieszkowski, Prolegomena do historiozofii, translated by A. Cieszkowski-son [in:] Idem, Prolegomena do historiozofii, Bóg i palingeneza oraz mniejsze pisma filozoficzne z lat 1838-1842, Warszawa 1972, p. 9).

[4] Ibid., p. 4.

[5] cf. S. Pieróg, Dialektyka i Objawienie w historiozofii Augusta Cieszkowskiego, „Nowa Krytyka” 1993, nr 4, p. 82.

[6] A. Cieszkowski, Notatki i szkice [in:] by Idem, Prolegomena do historiozofii, Bóg…, op. cit. p. 293–294.

[7] cf. Idem, Prolegomena…, op. cit. p. 21.

[8] Ibid., p. 18.

[9] Idem, Ojcze Nasz, t. 1, Poznań 1922, p. 59. In all the quotes from Ojcze Nasz [Our Father] I keep the original spelling.

[10] Ibid., p. 193.

[11] Idem, t. 2, Poznań 1922, p. 18.

[12] Idem, Prolegomena…, op cit., p. 30–31.

[13] cf. Idem, p. 47–49.

[14] Idem, Ojcze nasz, t. 1, op. cit., p. 144.

[15] Ibid., p. 3.

[16] Idem, Prolegomena…, op. cit., p. 48.

[17] Idem, Ojcze nasz, t. 1, op. cit., p. 116.

[18] A. Wawrzynowicz, Filozoficzne przesłanki holizmu historiozoficznego w myśli Augusta Cieszkowskiego, Poznań 2010, p. 142

[19] G. Kubski, Co egzegetom po Cieszkowskim? [in:] Co po Auguście Cieszkowskim? Spojrzenie po 120. latach, red. J. Banaszak, Poznań 2012, p. 39.

[20] Ibid., p. 46–47

Comments (0)