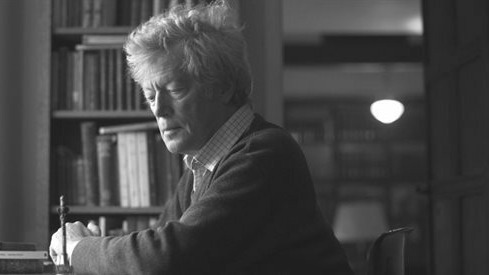

Sir Roger Scruton - "Beauty, Piety and Desecration" - an Elegiac Recollection in Tranquility

“Nature is never spent. There lives the

dearest freshness deep down things”

(G.M. Hopkins)

It is immensely difficult to write about an erudite scholar and philosopher such as Sir Roger Scruton since his great pageant of interests, intellectual involvements and possible specialties makes one at once question the fundamental character of his motivations. In his collection of Gifford Lectures entitled The Face of God (2010), Scruton proves that man was created in the divine image but since his fall he has become the protagonist of the postlapsarian drama in which his soul remains at stake in the world of the senses, “abysmality” and wealth-seeking model of consumption. Scruton finds his own way in this world but he shares it with others since, as a conservative thinker, he looks at the past, history and tradition to preserve what was most valuable in its heritage, what constituted the triad of the face of God, of man and that of earth. In all this, he finds sequestered his own identity, “self steeped and pashed”, as the English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889) puts it, immersed in the oikophilia, the love of England, his home country, which he often recalls with “gentle regrets” and nostalgia to preserve for and bequeath to posterity. The return to the source, to his childhood and teens which shaped his way of life and the source from which he drew abundantly throughout his life makes him reflect on the superiority of the ideal he was bred to honor and respect in the generation that has been slowly bidding adieu to the world. Scruton was aware that the shift of focus from speculative investigations to experience found modern man lost in a variety of multiplicities in which he could hardly find the right path. Only as a mature philosopher, scholar and aesthete was he able to draw from the redemptive knowledge anchored in the past to shape his conservative views which helped him survive in the world in which pessimism, in the political turmoil of the twentieth century, was more triumphant than “pursuit of life, happiness and freedom.” A few remarks concerning the major themes in Scruton’s writing such as a fascination with beauty, pious thinking, religion, the meaning of self, love of home in the world rather inimical to such virtues since desecrated with too much trust in the physical senses rather than the intellect will be the focus of concern. Scruton’s versatility owes much to his love of philosophy, music and literature, the reading and contemplating of which influenced his style of writing which many a scholar can hardly surpass.

1. The universals, fundamentals and the Self

Standing in the “face of God, man and earth” Sir Roger Scruton (1944-2020), the English philosopher, erudite and a conservative thinker of international acclaim, shared similar views on ethics, aesthetics, environmental interests, love of philosophy and the belief in God with many a religious poet or writer, though he has never been recognized as a religious scholar. Scruton wrote a book of poetry and four novels and stories but he did not recognize himself as a poet or a novelist who wrote literary works; nevertheless, as it seems, a literary thinking underpins his philosophical works and proves that, as an erudite scholar, he was well-educated in world literature. However, he wrote, primarily, about music and visual art and composed his own musical works which prompted him to make references to literature in which he found, as in visual arts, inspiration for his philosophical considerations[1]. He was a versatile scholar for whom philosophy opened the gate to understand other arts or, contrariwise, it was the other arts that paved the way for his philosophical ideas. In this sense he reminds one of Martin Heidegger (1889-1979) whose aesthetic philosophy was mainly inspired by his reading of German poets such as Jean Paul, Rilke or Hőlderlin, the latter one his major literary avatar and an intellectual custodian. Scruton’s faith, views, mainly conservative in nature, his aesthetic thoughts and reflections on world life and environment were presented in more than forty books in which he realized himself as someone dedicated to the transcendental world indirectly, through a love of the arts and an insightful reading of philosophers whose ideas he studied, contemplated, and interpreted in his own original way.

In an article entitled “A Candle to Roger” Francis X. Maier[2] begins his reflections in memory of the English philosopher with Richard Weaver’s famous phrase “ideas have consequences” which is the title of Weaver’s famous book. Maier adds, however, that “not all of them [the ideas] are good”. Scruton is addressed as “a relentlessly sane writer” and the scholar with the power of intellectual thinking that “has a value beyond price” especially in times like ours, that is in the first two decades of the twenty first century, in which, as Maier puts it, “false gods have big appetites”. Scruton’s mind is rightly described as one of “a man of dry English wit skilled at decapitating intellectual blowhards and translating complex ideas into their human consequences – consequences understandable to ordinary, reasonably intelligent people” (Maier). In a brief memorial Maier summarizes a few but major ideas that Scruton was faithful to and which are “worth noting”. Among his most seminal beliefs, we find Scruton’s concerns with religion, science, self-identity, man as subject and not an object of the world, his dedication to fundamental and universal beliefs and ideals that form the basis of Western society, the loss of which can be observed in the recent history of the West.

The first of the mentioned values is religion which, as Scruton proves in his books, resists the human temptation of idolatry often paid to “false gods” and “boutique spiritualities” (Maier). The latter, as is remarked, are always mercurial, evanescent, and can soon turn out deceptive as they prompt man to delude himself with the world of the senses or with “addictive and ultimately destructive fantasies such as the inevitability of progress or the withering away of the state” (Maier). This view is central in Weaver’s book Ideas have Consequences in which an American predecessor of Scruton and a conservative thinker, philologist and scholar, attempts at explaining the reason for which modern man lost trust in transcendentalia in favour of the world of the senses that serve only to cater for temporary desires. Man, as Weaver puts it, committed a “long series of abdications” which were the consequences of his disbelief in universals; which left a condition of “abysmality”, his acting in practice but without theory, and without authority, so he started “consoling himself with the thought that life should be experimental” (Ideas have Consequences 7).

A conservative by convictions, traditional in thinking, immersed in classical antiquity and philosophical thought that defended authority and the human subject, Sir Roger Scruton was a dedicated advocate of Richard Weaver’s and Russel Kirk’s conservative thoughts which were articulated in the former’s Ideas have Consequences (1948) and in the latter’s The Conservative Mind (1953), published when Scruton was still in his teens. As Maier observes, Scruton never rejected science and materialism which he respected as important to accelerate the growth of the world of civilization but he accepted them only on condition that they do not become avatars to be idolatrously worshipped beyond other ideas of fundamental importance. Scruton believed in the universals and fundamentals on which world culture had been set up and which had survived over the centuries. His homage to creation as one of “a sacred quality”, one of “sacramental beauty and aliveness” conducted him to see the world “in the face of God”, in all its spiritual and aesthetic heritage, one in which human dignity finds its best “stewardship” (Maier). Scruton’s confrontation with what he calls the “dross of this world” (Gentle Regrets loc. 1342), the world of the “eclipse of transcendence” (Charles Taylor A Secular Age 301-308) can be evinced not only by his great dedication to music and the arts in which he finds the transpiring presence of the transcendental but also by his glorification of beauty in “all great arts” (music, literature, and architecture) which show themselves as the “resonance of fertility and a spirit of organic harmony, right order, and purpose” (Maier). Beauty, as Scruton often reminds us, “like memory and history” calls us to obey certain standards and order and become critical when confronted with “the compulsive modern taste for ugliness and desecration” (Maier). It is also Scruton’s incessant care for other people with respect to their freedom and recognition of the “bonds of membership” that show him as man of strong political loyalties. As is his major belief, it is not only what links man to previous generations but what enables man to “regard the interests and needs of strangers as one’s concern” (The Roger Scruton Reader loc. 174), which he proved when travelling to the East of Europe under the Communist regime. In such a context Scruton finds America the best example of national loyalty, one that understands what is “first and foremost a nation”, a “community of strangers bound together by the love of the home that they share”(loc. 184). To find ground for such a community, one must first inquire of that which is the essence of the human self, the self “steeped and pashed”, as the poet G.M. Hopkins phrased it, the incarnate self and not fully the self if it is “without the body”. It is that meaning of the self that Scruton finds in the religious meaning of “self-denial” (the self that is faced with and dedicated to the divine through the love of another man) which allows “the saint or the bodhisattva to re-work the primal experience of community as a relation between himself and the transcendent meaning of the world” (The Face of God loc. 327).

In so presented a human condition with a subject that dominates over an object there reverberate poetic tones such as in Hopkins’ poem “As kingfishers catch fire” that sounds like a poetic prelude to Scruton’s The Face of God. Well familiar with Duns Scotus’s philosophy of individuality, Hopkins declares that man is a unique self, possessed with the gift of recognition of his own ontological status and self-conscious state of mind, which the following words make clear:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves – goes its self, myself it speaks and spells

Crying What I do is me: for that I came (The Major Works 129).

Man cannot be admitted otherwise but as a subject rather than an object, which becomes The Face of God’s major message to show Scruton as a follower of Wittgenstein’s “grammar of the first person case”; as we read in his Gifford Lectures which promote the idea of three faces, that of man, earth and God, the most important is that of “self-knowledge” as it remains always the privileged sphere of one’s own individuality. In Scruton’s words:

[…] it remains true that there is in each of us a sphere of self-knowledge that is privileged and that this sphere of self-knowledge defines the view from somewhere which is mine. Without that privileged sphere there would be no “I”: my world would be “I-less”, and therefore not mine or anyone’s (The Face of God loc. 543).

The words of a poet and a philosopher support the value of the human condition which is “both fundamental and mysterious” as it transcends the human world by making it appear different from the surrounding world. And the mystery is placed in the impossibility of explaining the fact that every creature “who can say “I” and thereby refer to himself is able to answer the question “why”? (543) The self is referred to as “a unitary substance, whose nature is infallibly revealed to me by my introspective thoughts”, the idea that supports the view of the self as subject and not as object, one that is “a unified centre of consciousness” able to justify one’s own beliefs, feelings and intentions (The Face of God).

Scruton’s belief in man’s calling and privilege of being subject recalls Hopkins whose philosophical poems reinforce the sense and power of human dignity. In all this, both the poet and the philosopher, do not shun away from the human power of sight. Hopkins executes his visions, no matter how spiritual, via “inscapes”, that is images which are like faces to reflect the inner power of “instress” and Scruton, despite the insanity of ubiquitous seeing and against the all-pervading “scopic regime of (post)modernity”, still finds in human sight that which communicates the message of “the residence of the unique, unrepeatable, human subject, a personal sovereignty over the body that pornography [a form of sacrilege] needs to erase and violate” (Maier).

2. “To what serves mortal beauty”

In Gentle Regrets Scruton writes about the visual virtue in the context of the body when he asserts that, “sex is either consecration or desecration, with no neutral territory between, and that nothing matters more than the customs, ceremonies, and rites with which we lift the body above its material need and reshape it as a soul” (Gentle Regrets loc. 1306). This does not mean that he rejects the beauty of man’s body; contrariwise, he recognizes it as an object of veneration in both life and art, the latter bearing no sense without carnal beauty displayed. He always looked at the body with “reverence for modesty and restraint” and with vigilance to the idea of the soul which he defines as something ineffably arcane when he recalls his emotional encounter with a young Polish female student (while lecturing in Poland), as he was attracted to “by the soul” rather than “by […] body, beautiful though it was” (loc. 1259). The soul, in his view, is something as mysterious and ineffable as the “true mystery of the Annunciation” he finds in the painting by Simone Martini of 1333. In the painted scene the Archangel Gabriel (the name “Gabriel” meaning “the giver of light”) is greeting the Virgin Mary to tell her of the conception of Jesus, which is suggested “by the fluttering cloak and spread wings” (Simone Martini‚ painting Annunciation). The moment of Mary’s distress on hearing of the words of the annunciation is portrayed as the mysteriously silent encounter of the “I” of the Angel with the “I” of a simple woman” (the “I” homophonic with the “eye”) (Gentle Regrets loc. 1266). The recollection of the Polish female student a propos Martini’s scene in the painting is not fortuitous as it shows a certain similar context of art and reality. There is only the difference between Mary who conceived of the Holy Spirit and the Polish girl who was seduced by the husband of the family with which she was once staying in England. The two encounters, one with an Angel and one with the physical man, show the two women in the state of anxiety, one formerly seduced and “confessing to her unchastities” before the writer and one for whom the meeting was the moment of consent to immaculately conceive of the Holy Spirit; one’s body desecrated and one’s consecrated.

What made the philosopher what he was and became later in life is unveiled in Gentle Regrets, the book which is a kind of autobiography and an account of what provided an incentive, both intellectual and spiritual, for his future life. Scruton explains how he was shaped as a scholar, thinker and writer, at first, as a religious atheist and finally a man of religious knowledge. He calls his “gentle regrets” a kind of “autobiographical excursion” which formed “part of some larger intellectual enterprise” (Gentle Regrets loc. 18) that was, mainly, due to his understanding, through reading, of “the concrete beginnings of some fairly abstract ideas” (Gentle Regrets). Scruton talks about “finding comfort” in “uncomfortable truths”, a lesson he learnt through life experience and his personal background. He explains his interest in and reading of books which were bequeathed to him by a certain librarian who, because of his emigration to Canada and an inability to carry the books with him, deposited them with the philosopher. Gentle Regrets shows the beginnings, the inspirations found in reading literature which awakened the young man’s interests in intellectual matters and paved the way for his future intellectual blooming. As George Steiner (1929-2020) remarks in his Grammars of Creation, the most important thing for life is the beginning, the “incipio” which comes back later on as it is the end that always contains the beginning.

Scruton’s autobiography reveals many interesting links that juxtapose his two experiences, his belonging to and embeddedness in the Western civilization in which he was born and bred and the experience of Communism which he sensed well while traveling in Eastern Europe and later by re-visiting those places after the Fall of the Wall in 1989. The visits, partly, showed that “ideas have consequences”, which is largely discussed in The Use of Pessimism, the politically-charged account of the condition in which he finds the contemporary world, the ominous doctrines and systems that are created to cheat and annihilate human beings. Besides defending the attitude of pessimism and warning against the “danger of false hope” and the trust in “the utopian fallacy” that Communism attempted to instil in people’s minds, Scruton was advocating a reasonable indulgence in freedom to avoid all the traps that might lead man to anarchy and “the planning fallacy”. His choice was that of such virtues as “love, friendship, learning, home, family, nature, and nation” which he found fundamental for the right development of human personality and identity. He resuscitated the philosophy of oikophilia which became his life manifesto, both philosophical and political, which were often supported in his books and lectures.

3. The Love of Home and Poetry

While commenting on Scruton’s aesthetic and philosophical works Mark Dooley declares that they reveal a “philosophy of Love” which can be “united by a single theme: the love of home.” (The Roger Scruton Reader loc 73) Though often criticized and even vilified as a reactionary nationalist, Scruton was a lover of home, a loyal citizen of his country, an advocate of “gentle and dignified patriotism” (Dooley). His understanding of the idea of the home country or fatherland was always clear and meant the place of one’s belonging and return even after a longer time of absence from home which was, as shown by Odysseus’ itineracy, a shelter-place to finalize earthly wanderings. What transpires is that Scruton’s writing is a frequently felt nostalgia for home which was manifest even at the funeral ceremony when his daughter read Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Darkling Thrush” over her father’s grave. It was one of Scruton’s favourite poems and a kind of emotional lyrics that shows man’s mourning over a desolate world, a world deprived of hope in a better future to come. Yet, as it is typical of a Victorian poem, the man taking a walk in the coppice is suddenly disturbed by a bursting thrush whose trilling is so beautiful that the stranger starts wondering how much more knowledge the bird possesses that the human being is missing:

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware (The Darling Thrush 44).

“The Darkling Thrush” bids farewell to the departing philosopher, it is a kind of rhapsodic requiem at Scruton’s mourning ceremony to announce the time of “crossing the bar” (Tennyson) and also, perhaps most symbolically, an adieu to the pre-pandemic world of relative tranquility no matter how dramatically inflicted with world disasters. The “happy good night air of the bird” heard over the decadent Victorian grove reverberates mysteriously with the prophetic “blessed Hope” for the future of which the poet was entirely unaware bring too concerned with worldly matters. According to Dooley, Scruton’s optimism (even if with intervals of pessimism) helped him survive, and conducted him “from alienation, loneliness and desecration back home to beauty and its sacred source”. It helps us, as Dooley observes,

turn away from desecration and ask ourselves instead what inspires us and what we should revere... We can turn our attention to things we love – the woods and streams of our native country, friends and family, the ‘starry heavens above’ – and ask ourselves what they tell us about our lives on earth, and how that life should be lived. And then we can look on the world of art, poetry and music and know that there is a real difference between the sacrilegious, with which we are alone and troubled, and the beautiful, with which we are in company and at home (The Roger Scruton Reader loc. 342).

Scruton seems to appreciate the Victorian aesthetic when writing on poetry or culture, the time in which men of letters and aesthetes often lamented over the degeneration of nature caused by the developing industry and the advancement of the world of technology that damaged the world of nature. It is similar in Hopkins’s poem “To what serves Mortal Beauty” (To what serves Mortal Beauty 167) that celebrates the secular, the joyful and visual “mortal beauty” that pleases the senses. The poet turns to the “love of home” which for him is a symbol of God, “home at hearts, heaven’s sweet meet”, something superior to the physical beauty, a “better” one, the divine grace. Victorians were great admirers of landscape and nature, the idea that Scruton is referencing to when talking about 19th century “artists, poets and composers” whose major duty was to “explore and implore the face of nature, eager for a direct and I-to-I encounter” (The Face of God 137). Hopkins, a Victorian, demonstrates it in his dialectical aesthetics of “instress” and “inscape”, indulging himself in the environmental description, an adoration of the natural world whose beauty is “stressed, instressed”; but he also finds the spiritual in nature to be primarily glorified and cared for.

Hardy’s poem “The Darkling Thrush”, so dear to Scruton, invokes the “abyssally dark” fin-de-siecle with the “twilight of gods”, the “eclipse of transcendence”, and, finally, the “death of God” as announced in Nietzsche‘s decadent diagnosis. The “darkling thrush” at winter’s dusk symbolizes the demise of an epoch, and the twilight of man’s life, death, what is now “spectre-grey” (as man’s gray hair is a sign of old age) as opposed to “the weakening eye of day”. The “dregs made desolate” refer to the fading beauty of a disappearing world of prosperity that turns into the music that dies out and is presented as the image of the “strings of broken lyres” rather than sounds; in the world of frosty winter all men “had sought their household fires” to shelter themselves in and warm themselves up. The “cloudy canopy” appears like a crypt from which the “century’s corpse” in the “growing gloom” is sticking out (“leaning out”) among mourning lamentations of the wind whose faint echoes reflect the sounds of “ancient pulses” of life and spirit, to cite Hardy’s poem again:

The land's sharp features seemed to be

The Century's corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

Still, the gloomy twilight vision of the thrush becomes, however, illuminated with “some blessed Hope” which is a promise of the diurnal shining of dawn that will bring the epiphanic message of the light of Resurrection.

Scruton‘s philosophical thinking made him aware that one must change the earthly home in order to ascend the one which is “alas away”. “The love of worldly home and the desire for home environment” is termed as “oikophilia” which in Greek implies “the love of one’s place”, home culture, the love of workplace and one’s community. The idea takes its origin in Kant’s aesthetic judgement that Scruton liked and studied and, at times, critically interpreted but always regarded as an intellectual and philosophizing challenge. In the context of the West Scruton finds home as the shelter of “hidden virtues” against “nihilism, anger and selfishness”. To seek home, the “old experience of home” is to find one’s inheritance as one’s private property, a value like freedom which Scruton always regarded as a prime virtue and the privilege of the nation especially while visiting and staying in the East of Europe[3].

It is in one’s own place and with the love of home that one can experience the sacred, freedom, and all consequent values that the Eastern European man lacked and was deprived of for decades. As Emily Dickinson confesses in one of her most seminal poems “I dwell in possibility, a fairer house than prose…”, the poet finds his environmental home in language, as it is “poetically [that] man dwells in the world” (Heidegger). The Western man’s preference has always been for local loyalty and traditional attachments, which is shown by Scruton’s philosophy in The Face of God when he addresses various aspects of oikophilia. A love of home is respect for environmental security and an invitation to look on things in their homescapes, love of beauty and respect for the sacred. As Thornbrooke puts it: “much of Scruton’s philosophy of the home is bound up with what one speaker referred to as those things that are ‘interred in the spirit of a people.’ That is to say, the common culture inherent to a people who share the bonds of land and community” (Love of Home). In the view of oikophilic philosophy the beautiful and the sacred can be connected to a man’s secure shelter place that could be destroyed by damaging propensities and attempts at desecration. The face of nature is landscape which turns toward man, and “the pursuit of beauty is the search for home” (The Face of God 137). Home is also a “cloistral refuge” form the world outside, the desire for intimacy which is also associated with “Eros”, a “sanctuary, a precinct threatened by pollution and protected by taboo” (114). As is remarked in The Face of God, home is not only an environment and a place as habitation but that which is within man, the dwelling place of God’s presence, the sanctity of the Temple as shown in the Book of Exodus.

Scruton’s The Face of God reveals how secularization appears as an immediate result of the eclipse or ignorance of transcendence and what destructive effects it can exercise on man and his environment. The choice of three faces, of a person, of the world and of God is to search and demonstrate how culture and nature can be damaged when man relies merely on his senses and abandons universals. The “practical result of banishing the reality which is perceived by the intellect” and “positing as reality that which is perceived by the senses” (Ideas have consequences 3) means, according to Weaver, the denial of “everything transcending experience”, the denial of truth, the consequence of rejecting logical realism and yielding to the temptation of modern empiricism. Born and bred in Buslingthorpe, Lincolnshire, a region of scenic landscapes and inspiring environments which illuminated with the “face of Earth”, Scruton remained in love not only with the private world of his community but also with the countryside and the people of his local village sharing their joy, excitement and mysteries of life. His predilection concerning landscape and love of land resembles that of English poets and writers such as Hopkins, Heaney or Thomas Hardy, and Tolkien, poets whose love of England was much like his own. Of the two mentioned faces described in The Face of God, the Face of Person and the Face of Earth have been near to the Face of God since they are connected with man who was created in the likeness of His image. In the human face (which resembles Hopkins’ inscape) one finds the face of God (what Hopkins called instress) that is reflected as well in the beauty of the natural world. A consecrated world is defended by God against man’s habit of desecration which is performed to destroy the face of Earth. Like Eros which is a sanctuary and a place of safety, so Nature should be a site free from pollution and protected from destruction. However, as we read in Scruton, “the temptation is to enter this place in a spirit of iconoclasm, destroying and masking the face”(The Face of God 113). Desecration destroys peace and love the consequence of which is the destruction of human relationships that results in an “ever expanding heartlessness” at the absence of human mutualities. God declares that He requires man to find a home in this world, a temple in which will be celebrated the rituals to “convey a clear conception of his nature and his presence”(114); however, man often rejects the “world [that] is charged with the grandeur of God”, the Earth that is rendered holy as the sacred place in which God finds himself at home. This is the foremost message that breaks through the Gifford Lectures entitled The Face of God.

Conclusion

Sir Roger Scruton passed away almost at the same time as another great philosopher and scholar George Steiner (1929-2020), as if both set up the date for their leaving of this world. Both versatile, both tired of mundane matters, they drew much from the world’s resources and deposits treating life with the sense of “real presence” which they fiound embodied in arts, philosophy, literature and religion. The desire to reconnect with the old orthodoxy and tradition was the major goal of their academic curricula and the destination of their aesthetic creation. Scruton was a lover of his country, sensitive to the beauty of landscape and the English countryside, the philosopher and the writer living in several places throughout his life and the noble Englishman enjoying his life on a farm where he would spend time on reading, writing and composing music. He was also reflecting and writing much about God, the topic he referenced to, among other books, in A Personal History of the Church of England. In the chapter “Draw near with Faith” one can sense that he was close to conversion but, as it were, still regarding himself unprepared and too embarrassed to make a final decision like a convert G.M. Hopkins. Hopkins was young when he “broke out of the immanent frame” to lean out the world’s window to see the other world, his home, which could have been reached by a “surprising new itinerary” (A Secular Age 755), the one opened up by conversion. Two of Hopkins’ poems, written before his conversion, “The Half Way House” and “Let me be to Thee as a circling Bird” are attempts to find the security of home, still “half-light” (half-lit) but later crowned with the finding of the “dominant of my range and state Love O my God to call Thee love and love” (“Let me be to Thee…”). Hesitation and indeterminacy are two states that characterize the time before conversion which are well described by Paul Mariani in his book on Hopkins’ life. Scruton used the term the Real Presence of God when he referred to the sacrament of the Eucharist but Hopkins as a convert believed in it, as found explained by Mariani who talks about the moment of conversion in the poet’s life. He writes that in Rome Hopkins received:

his best guarantee for the Real Presence in the Eucharist he so much desires now: no symbol but the ineffable thing itself, and there for the asking. In an instant, the interminable struggle of the past three years is over, and now the angel he has wrestled with day in and night out touches his hip and departs. And suddenly he sees what every pilgrim comes to see: that something has been lost even as something greater has been found (Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Life 16).

Conversion changed Hopkins’ entire life, the physical vision, his religious condition and his aesthetic attitude; the style of his writing becomes more vivid and one can sense the passion of God’s grandeur transpiring through the poems that follow.

Percy Bysshe Shelley writes in A Defence of Poetry that the poet and the philosopher (also a prophet) share much, sometimes are even the same, as they are constantly confronted with the three faces, that of the infinite or eternal, of man and of nature. Scruton was one to constantly remind us that love (and the sense of beauty) is “grace” [and he explains the etymology of grace coming from Latin “gratia”, also in “gratitude”] that rules out selfishness and inspires sacrifice as a prior virtue; hence, as Dooley emphasizes, there is no other motive to serve others and one’s country but through “the shared love for our home. It is a motive in ordinary people. It can provide a foundation both for a conservative approach to institutions and a conservationist approach to the land” (The Scruton Reader loc. 308). What can be particularly valued in Scruton’s lore is his belief in the nation whose major priority is language and not a place united by institutions and borders; whose virtue is religion and high culture in which “spiritual things” make one an artist, a poet, a composer and an acute observer of the world (and its environment). He saw his homeland not only as “mortal beauty” but over and above all as that of a “nature [that] is never spent” with the “dearest freshness deep down things” (Hopkins), the spiritual abode to devote the rest of his life to. This love he wished to express with affirmation and preservation (hence conservation as he himself always remained a conservative scholar). The form of conservatism that Scruton practised gives unity and coherence to his beliefs, from “gentle regrets” to philosophy, from music composing to private life, and from dwelling in communion with nature (his farm) to performing his academic life. His world like that of a poet was charged with instress, and reverberated with the polyphony of inscapes, meticulously portrayed visions which he experienced and shared with others.

As is declared in his most seminal study The West and the Rest the former is firmly anchored in the heritage of Roman law and Christianity, the genesis of which is the rule of law and the presence of the absolute. He finds in the West the source of values which could not be pursued by the East especially in the 20th century in which the West served as a paragon of loyalty to the land and the law and the East (the Rest) remained in the “system that repressed people”. Scruton saw the reality of the East while traveling there under the various Communist regimes and he attempted to be an intellectual custodian to protect “the godless void” that the contemporary world was and still is faced with to secure man who is mortally threatened by ideology whose pernicious effects were to destroy humanity for the decades that followed. It is the East of Europe that owes much to Scruton’s teaching and advocacy and so, in the second year of the anniversary of his death I deem it an honour to celebrate Him in perpetuam rei memoriam.

*This article was originally published in the book entitled Tradition and Change. Scruton’s Philosophy and its Meaning for Contemporary Europe, European Conservatives and Reformists, Warszawa 2022.

Works Cited

Barańczak, Stanisław. Thomas Hardy 55 wierszy edited by S. Barańczak. Wydawnictwo Znak Kraków, 1993, p. 44.

Dooley, Mark. The Roger Scruton Reader. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009. Kindle edition

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. “As kingfishers catch fire.” G.M. Hopkins The Major Works. Oxford University Press, 2002, edited by Catherine Phillips, p. 129.

Maier, Francis X., “A Candle for Roger.” The Catholic Thing, 11 Nov., 2021.

Scruton, Roger. The Face of God The Gifford Lectures 2010. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2012. Kindle edition.

Scruton, Roger, Gentle Regrets: Thoughts from a Life. Bloomsbury Reader, 2005. Kindle edition.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

Weaver, Richard M. Ideas have Consequences. The University of Chicago Press, 1948.

[1] Chief among his great musical works is The Aesthetics of Music (Oxford University Press, 1997) which I was referring to in my article “Kultura jest Domem Bycia…” written in Polish in: Filozoficzne aspekty literatury. Między aksjologią a estetyką (Wyd. Naukowe TYGIEL, Lublin 2021), p.127-139.

[2] Francis X. Maier, “A Candle for Roger” in The Catholic Thing, 11 Nov., 2021 at: https://www.thecatholicthing.org/2021/11/11/a-candle-for-roger/ 20 Dec., 2021, 21:03. In the paragraph that follows I refer to this article and all citations are from Maier’s text.

[3] There is an interesting article on Scruton’s love of home “The Love of Home What Roger Scruton offers America” by Andrew Thornebrooke in The Rearguard (13 Jan. 2021) at: https://medium.com/rearguard/the-love-of-home-19fe9c424e67 13th January, 2022.

Foto: Frantzesco Kangaris /eyevine/EAST NEWS

Comments (0)