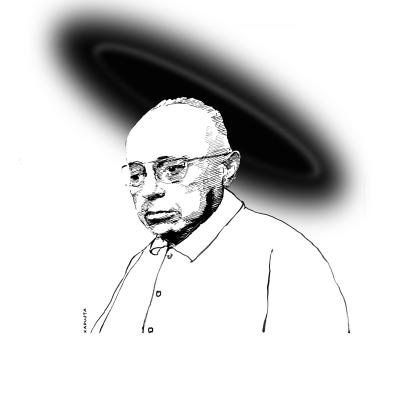

STANISŁAW LEM: THE PHILOSOPHER’S VISION ON THE FLOE [1969]

Ladies and gentlemen, there are an infinite number of dimensions of configurational space in which one can place the point of view of what has been said so far. After all, from names such as St Thomas, Plato and Aristotle go the roots into the entire universe of human thought, so that, in fact, the libraries of the entire world should be brought here and then - I am joking - it would be possible to discuss and put things in some proper order. So, I will sit at the opposite pole of the axis and seemingly not talk about these thinkers at all.

I will start with what is occupying me at the moment, namely I am now writing a book related to the issue of futurology, so I have to embrace authors building predictions of human existence as far into the future as possible. I wanted to find a philosopher who would be, as it were, a counterbalance, a juxtaposition to the professionals of futurology, and based on a random sample, I took Marcuse. He is a humanistically and philosophically educated man, so to speak, an heir in contemporaneity to the grand old works of systematic philosophy, he is a man who is comprehensively disgusted and dissatisfied with the world of today and its devices, and he has against him that powerful clan of futurologists, which may be represented by Herman Kahn. On a purely formal plane, the difference between the foetuses of futurology and philosophy is that every philosophical direction, every school refines a single system, that within it there are findings pretending to be one and the same, whereas the futurologist, aware of things, does not build a single forecast, but provides a whole set of alternative ones. Both the philosophy of being and of should within each historically established or existing school say that it is so and so and that it should so and so. On the other hand, the futurologist does not merely provide forecasts, like an astronomer predicting successive solar eclipses, but brings predictions mixed with recommendations and warnings, as it were, in one package. For the futurologists of this direction, which today is a leading force and Kahn’s name is only a conventional sign, touching on what is similar in these efforts, in truth only instrumental values count.

It seems to these futurologists that, because they do not admit to any particular philosophical school of valuation in particular, they have thus extracted themselves, as it were, from the precincts of typical philosophical disputes concerning values, having left them behind as obsolete junk. In practice, they are, as can be easily detected, eclectic, and the glue that joins the pieces, taken from different doctrines, is, for them, a narrow pragmatism. In constructing their forecasts and building these worlds of the future - once standard and once accommodating deviations from the standard - they treat cultural phenomena as secondary or tertiary. If we disregard their verbal objections and comments, they regard culture as devoid of all autonomy; they do not even consider it as the lubricant that in a machine is supposed to cushion the cooperation of the gears. Against these practices, aware of things, stands the philosopher, who represents the traditions of ontic and axiological thought while proving completely powerless against futurologists. Not only in the obvious sense that he is not, like those others, financed by powerful corporations, that the ruling circles do not stand behind him. Above all, he is, therefore, powerless because, in the ocean of detected correlations and trends, statistics, and formulas, he can only counter his veto and hurl his thunderbolts at what is now so often called “the establishment”. In this way, a man who admits to non-instrumental values, those with which culture stands, with which I would be happy to sympathise, shows his own helplessness because moral indignation can be an initial impulse, awakening from lethargy, calling for thought work, but it cannot replace real programmes of action. The situation of such a disempowerment of philosophy irritates and frightens me because I, arriving at it by non-academic means, privately, would never consider it to be a discipline, capable only of giving information to Pascal’s reeds, that in fact, the only role of philosophy is to inform this reed who and what is breaking it, and that when it does so, its role is already fulfilled. If it is not the case, as it used to be, that existence is given to us unquestionably and at most, we have to describe it, but that we can shape it in an unimaginable variety of ways, then in a situation of similar freedom, it is necessary to have a guide, and it is the philosophy that should be this guide. At the same time, it is incapable of doing so at present. Therein lies the antinomy of a culture struck by the invasion of technical civilisation.

Futurologists are indeed better informed than we are and only use this better information in an altogether perverse way; methodologically unmodernised, uninformed philosophy turns out to be powerless, capable only of idle protest. Specific incidents, such as the French events in May, made Marcuse the hero of the day - completely unwittingly - and, at the same time, the symbol of so-called “contestation”. With this exaltation, he himself was seemingly satisfied but also confused for the lack of a concrete programme. On the other hand, futurologists who observe social phenomena but do not interfere in them as political activists, i.e., who wish to maintain the appearance of men of science who study society with the objectivity of star and planetary scientists, do indeed have a programme. In order to be a politician, as in order to be a philosopher, one does not necessarily have to give speeches at rallies or publish ontological works. Futurologists are thus both politically and philosophically active; only they do not explicitly admit it. In practice, the guiding thread of Herman Kahn’s construction is philosophical pragmatism and the political stance of preserving the status quo. It is to be believed that when the noble utopian clashes with the common-sense pragmatist, the latter will always prevail in the end. In this light, in terms of returning to the sources, I speak of the three great names mentioned here. I confess that I do not really know what more can be done beyond acts of thought expressing allegiance to the venerable traditions of the masters of historical wisdom.

Plato, Saint Thomas, Aristotle, perfectly, but actually, the acts of such acknowledgement of their heritage seem to me insufficient. History has brought us to a point where everything has become instrumentalised. In Kahn’s book, for example, one reads of possible transformations of faith, of the emergence of new “mutations” of faith in the 21st century, if at that time, the products of technology were to dominate man intellectually: he imagines that some creed “á rebours” could then arise, deriving the value of humanity precisely from the fact of man’s “mental inferiority” to rational machinery. Some kind of masochism, displaced to transcendence.

The intellectual weakness, the fallibility, the insignificance of man juxtaposed with his own creation would become the seed of a new metaphysics. Kahn treats such ideas purely instrumentally, i.e. he wonders whether and how the state should apply the brakes to newly emerging faiths and whether it might not, in some cases, be better to apply an amplifier to them.

On the level of a kind of “futurology of faith”, this concept seems rather primitive to me, but it reveals the futurologist’s attitude to non-instrumental values: they are nothing more than elements of reckoning, mere building blocks for constructing appropriate patterns. It is quite as if a similar stance actually allows one to step beyond the realm of axiological conflicts, decisions about values, although there is no such place for practical actions and it cannot exist. However, in practice, this total instrumentalisation triumphs because it looks not only as if the Lord God is on the side of the stronger battalions but also that the better-informed win. Thus, traditional philosophy is on such a floe, on such a very beautifully constructed crystal that is moving in an unknown direction, lifted by the waves of unleashed technology. Such a philosophy seems to me to be a pigeonhole, a work that is almost, I would say, escapist. Meanwhile, those there approve of all changes, relativising all values, not only in the field of norms and state laws, that is, in the field of culture, but in the hitherto untouched terrain of man’s bodily organisation. For the invasion of the body - biotechnology - is beginning.

A few decades ago, one could still echo the poet’s words that each epoch had its own goals because the lifespan of one generation was shorter than the period of great sociotechnical and cultural transformations. But the time of good immobility is no longer coming back. A few decades ago, people began to fly using fabric, bed sheets and umbrella wire, but now fly in a completely different way - and also to other, extraterrestrial places. So, if biotechnological evolution is launched at similar paces, absolutely anything can be done with the human body, and then we will be divested of all guiding understandings, directional signs, and messages about what is inviolable and what is necessary.

And yet reason has always strived to detect in the world its necessary qualities. When these disappear, we find ourselves in a situation similar to cosmonauts in stellar space, where there is no up or bottom, where everything is possible due to the absence of unassailable support, and where it is absolutely unclear what to do.

For, indeed, if one acquires, thanks to perfect technologies, almost perfect freedom of action, then no empirical, and therefore instrumental, calculations can answer the question of what one should do. Those who rush to our aid, like the futurologists themselves, do not propose any code of enduring values, and the only principle derived from their practical actions is this: the machine is moving, so everything must be done to keep it going. If one can change hearts, one should change hearts; if one can replace the lungs with a synthetic organ, then this should be done, and so on. In this way, in practice, what needs to be done is determined by what can currently be done. Such an automatic equating of the attainable with the proper seems to me to be a trend towards the nihilisation of culture, as axiology is replaced by a completely unfounded belief that the very order in which the sciences are able to provide us with their discoveries should be the guide to human destiny.

To conclude, I would like to emphasise the outlined irreducibility: philosophy is its own thing, and futurology is its own thing, and if the right combination of thoughts and forces is not achieved, technology will ultimately take culture by the head, incorporate autonomous values as parts of arithmetic operations into the calculation, and lead us to historically unprecedented states. It is one thing to have a personally located evil, an Attila or various historical monsters, and quite another to have a perfectly educated person equipped with the best knowledge, who accepts the state of complete relativisation in the field of culture and who will not even think of questioning this direction of movement. With the optimistic assistance of futurologists, technology can devour philosophy, leaving behind, as Borges once said in a different context, a purely “ludic” pursuit - the search not for the truth of findings and not for superior values but only the construction of fantasy systems in thought that arouse great wonder.

Read also

Empiricism and Culture

If life, in the eye of the evolutionary biologist, is a game played by a planetary coalition of organisms in which Nature is the opponent, then the entirety of the rules of such a game — biosphere versus necrosphere — is contained in the theory of homeostasis.

Comments (0)