According to Aristotle’s classical definition, politics is the rational concern for the common good. The question arises, however, as to how we understand the constituent parts of this definition: reason, concern, community and especially the good. The answers to these questions will not be given by politics because they come from the pre-political sphere: philosophical, moral and, above all, religious. This is particularly evident in modern times when secularised societies reject belief in God. This is also reflected in politics.

All civilisations in the history of the world have been built on the foundation of religion. As Thomas S. Eliot aptly observed, “politics is a function of culture, and the heart of culture is religion”. The first entirely secular, rather than religious, attempt to build a new civilisation in human history was the Enlightenment project. In the 18th century, philosophers developed a secular programme for the overall reconstruction of the world, which had the character of a quasi-religion. Their starting point was the conviction that social reality was so utterly tainted by the evil that it required a radical transformation: a revolution.

The Enlightenment: the dream of creating a new world

This was, for example, the vision of one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers, Johann-Jacques Rousseau, who proposed replacing the Decalogue with a Pentalogue he had formulated. The first of its five commandments, written down in the Social Contract, proclaimed “the existence of a powerful, intelligent, gracious, provident and foreseeing deity, the Will of the People”. This popular will was, in his view, to be endowed with divine attributes and therefore “indivisible, infallible and absolute”. For the voluntas populi to acquire divine attributes, all citizens must transfer their feelings, beliefs and convictions to it. Then they themselves will receive new views, laws, beliefs and ways of life from it. They will become “new people”.

The religion of the universal will did not tolerate even the slightest opposition. Rousseau wrote: “Anyone who ventures to say ‘Outside the Church is no salvation’ should be driven from the State”. And further on, “If anyone publicly recognises these dogmas [the five dogmas of the Social Contract], and then behaves as if he doesn’t believe them, let him be punished by death: he has committed the worst of all crimes - lying before the law”.

Not long afterwards, when Rousseau’s disciples came to power in France, with Maximilian Robespierre, the most loyal of them, at the head, thousands of people were sent to the guillotine for even minor offences.

Another Enlightenment philosopher, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, proclaimed the necessity of overthrowing “that abominable edifice of sheer nonsense which is Christianity and the Catholic religion”, proposing the proclamation of a “religion of reason” instead. It was Reason that was to become the absolute legislator and judge, the sole source of laws and morality before which all other authorities had to give way. Similar demands appeared in the writings or speeches of the most prominent representatives of the Enlightenment philosophy. Their thought fertilised the minds of rulers and political elites, for whom the greatest authority was no longer the Pope, but Voltaire, raising his famous war cry against the Church: “Let us crush the evil thing!”.

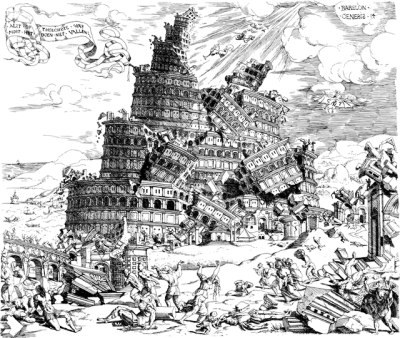

One of Voltaire’s most faithful disciples was King Frederick II of Prussia, who built his modern state on a paradigm that contradicted centuries of Christian experience. A highly telling insight into his ideological motivations may be found in a satire on the Church, which the Prussian monarch wrote in December 1770 at his palace in Potsdam. Paraphrasing St John’s style from Revelation, Frederick II wrote: “When my rapture had passed, I saw a great city. It was, it seemed to me, inhabited by people who had sprung from a cadmium dragon sowing as they fought fiercely with one another. When I asked about the name of the city, they told me that they had named it Zion, but its real name was Abomination. And the material of which it was built is not at all like that of which we build our cities. So I ask the spirit: "What is this?". The phantom replied: "The foundations are of delusion, and the mortar is mixed from miracles, and the stone blocks come from the quarry of Purgatory and the shinier ones from indulgences". Understanding nothing of her words, I watched as the city was built. It was fortified as was customary in antiquity - more or less as Babylon was depicted. It was encircled by thick, high walls with soaring towers called the tower of folly, the tower of superstition, the tower of delusion, the tower of fanaticism and finally, the tower of the devil. This one was to be the tallest”.

The Prussian ruler went on to describe how, over the centuries, the goddess of wisdom had sent successive hordes into battle to conquer the grim fortress. It was stormed by Cathars, Waldensians, Hussites and Protestants, but their attacks were repulsed. Finally, the fortress was conquered by the last group - the Encyclopaedists, who were led to victory by the charismatic Voltaire. In fact, the latter’s ideas gained a chance to be put into practice twenty years after Frederick wrote the pamphlet quoted above when the Great Revolution broke out in France.

The French Revolution: a bloodbath

Contemporary Italian scholar Rosa Alberoni writes that the French Revolution was a war declared on Catholicism by the “religion of the Enlightenment”. But what deity did the revolutionaries serve? In her view, first, it was the god of the deists, the “great watchmaker” who created the world and forgot it, then the god of the Freemasons, conceived as the “great architect”, then the idol of the “political body”, identified with the Republic and the Will of the People, and finally the goddess of Reason.

This last statement was not entirely a metaphor: on 10 November 1793, in place of the altar in Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral, revolutionaries erected an imitation of Olympus, on top of which stood - as the personification of Reason - the dancer of the capital’s opera house, Mademoiselle Maillard, dressed in a white dress, blue coat and red cap. As she took her seat on the throne, a laudatory hymn was sounded in her honour. Portraits of the new saints hung in the cathedral: Robespierre, Marat and other revolutionary leaders. A month earlier, the Convention abolished the Christian calendar and replaced it with a revolutionary one. The new calendar no longer began with the birth of Christ, but with 22 September 1792 - so the turning point in human history was to be the day Louis XVI was arrested. Everything that could be associated with Christianity was eradicated: clergy were murdered, the priestly state abolished, religious symbols removed, churches destroyed, cemeteries vandalised, and all holidays and even Sundays were cancelled. In the end, it was Diderot who said: “The world will not be happy until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest”. All the aforementioned actions served one purpose: the destruction of Christian civilisation and the Catholic Church to create in its place a “new man”, a “new nation”, and a “new world”.

The revolution moved towards this in stages. The first step was the abolition of the clerical state by the revolutionary authorities in 1789 and the confiscation of all church property. Then, by decree of 13 February 1790, perpetual vows were banned and all male and female religious orders were dissolved except those engaged in education or charity. Later, on 12 July 1790, the Constituent voted for the so-called civil constitution of the clergy, which abolished 51 of the 134 existing dioceses and a quarter of the parishes in France. This destroyed the parish system, which represented the interests of the peasantry vis-à-vis the state. For generations, it had been the most important institution in France for providing the countryside with protection and a sense of security. The idea was that the people of the third state could not find support in the Church but would seek it in the embrace of the secular state.

The civil constitution of the clergy made bishops and parish priests state officials. They could only take up their positions through elections, in which not only Catholics but all citizens of the department, including Protestants, Jews or atheists, were entitled to participate. A wealth census was also introduced, favouring those who paid more taxes. As a result, the referral of a parish priest to a particular village was decided not by its inhabitants but by the wealthy bourgeoisie, on top of which were often dissenters or non-believers. The revolutionaries intended to rigorously respect the new law. They required all clergy to take an oath to the constitution. Those who failed to do so were deprived of their rights to exercise priestly ministry.

The vast majority of bishops (except four) and more than half of the parish priests did not accept the new law. The intolerant authorities launched bloody repression against them: in 1792, three hierarchs and 300 priests were executed in Paris alone, and many were killed in other regions of the country. As many as 40,000 clergies were exiled and found refuge abroad. In the autumn of the same year, a concentration camp for priests was set up at Rochefort-sur-Mer, where 829 were placed, 547 of whom died in inhuman conditions (in 1995, John Paul II beatified 64 of them). In defence of the persecuted Church, a peasant uprising broke out in the Vendée, bloodily suppressed by the revolutionary authorities, who committed the first genocide in modern European history.

On 10 November 1793, the National Convention abolished Catholic worship. It was on this day that the aforementioned profanation at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris took place, followed by the removal of all Christian symbolism from public spaces. Some 8,000 priests, monks and nuns were then murdered. The destructive fury turned not only against the people. It is calculated that about a third of all art monuments in France were damaged or irretrievably lost during the revolution. The main targets of the attacks were ecclesiastical buildings: temples, monasteries, chapels, seminaries, bishop’s palaces, libraries and church archives, as well as the objects they contained, such as tombstones, sculptures, religious paintings, liturgical vessels, organs, bells, reliquaries, book collections and so on. The historian Jean de Viguerie writes that in the last decade of the 18th century, all churches in France were closed for some time (from a few weeks to several years). Some were demolished or turned into stables, barracks, feed stores or other facilities.

The terror was bearing fruit. Almost half of the diocesan priests signed the civil constitution of the clergy, in fact joining the schism. Later, one in two of them abandoned their priestly ministry under pressure from the authorities. For a dozen years or so, people became weaned from attending Mass and partaking in the sacraments. While in 1789, as many as 90 percent of the French celebrated Easter, in 1801 it was only 50 percent. The bloody persecution undoubtedly contributed to the rapid secularisation of the country.

Jean de Viguerie puts forward the thesis that de-Christianisation could have been even greater had it not been for the resistance of a whole host of Catholics. It was punishable by death to lead a religious life. Yet, despite this, sisters formed clandestine convents and sometimes paid with their heads, such as the 16 Carmelite nuns of Compiegne and the 13 Ursulines of Valenciennes.

Communism as a new religion

The French Revolution was, in a sense, a paradigmatic event. The same mechanism of cracking down on the Church was later applied in countries where revolutionary anticlerical forces came to power, such as the Soviet Union, Mexico and Spain. Particularly hostile to religion was the communist ideology, which ruled at the height of its power (in 1978) in as many as 23 countries of the world, in which almost a quarter of humanity lived.

Communism, despite its declarations of atheism, was something of a secular religion. For it had a pattern characteristic of religious belief. In it, progress took the place of providence. The classless society of the future was the promised paradise on earth, a surrogate for the Kingdom of Heaven. Instead of Christian dogmas, the Marxist doctrine was emerging. The Teaching Office of the Church was giving way to the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The latter was becoming as infallible as the Pope (with Catholics) or the Universal Council (with the Orthodox). Marx’s “Capital” dethroned the Bible. Portraits of communist leaders were part of the canon of Orthodox icons. Images of Marx, Engels and Lenin appeared like a theophany of the Holy Trinity. The worship of the infant Lenin resembled the veneration paid to the infant Jesus. The holiest shrine of communism remained Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow. Ultimately, the place of God as the supreme legislator was replaced by the man himself, or rather his collective representation - the Party.

The Communists perfected the methods of the crackdown on the Church initiated by the French revolutionaries. In 1922, the Soviet authorities established the Union of Militant Godless Men. The organisation was guided by Marx, who called religion the opium of the people and proclaimed that the only obstacle to the world communist revolution remained Jesus Christ. The institution became an instrument of the policy of forced atheisation of society. In the same year, it began publishing its press organ, the daily “Bezbożnik”, whose circulation reached 200,000 copies. The two weeklies “Atieist” and “Antirielioznik” had a mass circulation of one and a half million copies.

The Soviets destroyed Christian churches. In Kyiv alone, they demolished 98 Orthodox churches. Many closed churches and monasteries were turned into public premises, such as warehouses, factories, shops, bus stations, hospitals and even city toilets. Across the country, few Orthodox churches and a small number of Roman Catholic churches remained open. The authorities banned public prayers and the celebration of holidays. Public works, so-called social acts, were often organised on Sundays to prevent people from celebrating. On Christmas and Easter, “anti-religious carnivals” moved through the streets of major cities, whose participants mocked Jesus and the Mother of God. In Leningrad alone, twenty blasphemous masquerade processions took place on Christmas Day 1924. Some ended with the public burning of icons. Troops of activists called “udarniks” went from house to house, intimidating people and forcing them to sign petitions requesting the closure of Orthodox churches or churches.

Clergy were murdered en masse. Alexander Yakovlev’s special commission calculated that between 1917 and 1985, the Soviet regime murdered some 200,000 clergies of various denominations and arrested 300,000. In addition - just for adherence to the Christian faith - many laymen were killed, but their exact number could not be determined. The Russian Orthodox Church suffered the greatest losses. Between 1918 and 1939 alone, the Bolsheviks killed more than 130 bishops of this denomination. The Yakovlev Commission also documented the destruction of 40,000 Orthodox churches and churches and more than half of the mosques and synagogues. Many of these were priceless historical monuments. They were usually looted and profaned before being demolished.

New ideologies instead of the “end of history”

When communism collapsed, many commentators rejoiced that the days of atheistic ideologies fighting against the Catholic Church were a thing of the past. However, this optimism, common at the time, was not shared by St John Paul II. In his 1994 interview-transcending the threshold of hope, he told the Italian journalist Vittorio Messori: “The collapse of communism opens up a retrospective of the typical thinking and action of modern civilisation, especially the European civilisation that gave birth to communism. Alongside its undoubted achievements in many fields, it is also a civilisation of many mistakes and abusing man, exploiting him in various ways. A civilisation which continues to clothe itself with structures of force and violence, both political and cultural (especially the mass media), to impose these errors and abuses on humanity. (...) Who is responsible for this? Responsible is man, people, ideologies, and philosophical systems. I would say, responsible is the struggle against God, the systematic elimination of everything Christian, which has largely dominated Western thinking and life for three centuries. Marxist collectivism is only a 'worse edition' of this very programme. It can be said that today this programme reveals all its dangerous character and at the same time all its weaknesses.”

John Paul II, therefore, did not succumb to the euphoria of those who at the time prophesied the “end of history” but rather anticipated new dangers, growing out of the same ideological trunk as communism. We see this with our own eyes today as new ideologies emerge, claiming to be scientific and aiming to usher in a new order. Like other post-Enlightenment currents, they are guided by the slogan of human emancipation. In their view, to fulfil his potential in life, man should liberate himself from everything that limits his possibilities. At one time, revolutionaries proclaimed that he should free himself from the social structures constraining him, private property, Christian religion or traditional morality. The current phase of emancipation goes much further. Namely, it postulates the liberation of humanity no longer only from parenthood and motherhood, i.e. the division between father and mother, but even from its own gender, since the division of the sexes into male and female supposedly limits the human being. The modern anthropological revolution thus proclaims the complete liberation of man from nature. By doing so, human beings grant themselves almost divine prerogatives.

Enemy number one for this ideology, as for its predecessors in the past, is again the Catholic Church, defending not only revealed truth but also natural law and common sense.

Read also

Conservative and Christian Sources of Modern Ecological Thought

When St Justin the Philosopher debated with pagan sages in the second century after Christ, he heard from them: show me your writings and we will tell you who you are.

Comments (0)