1. The sense of form

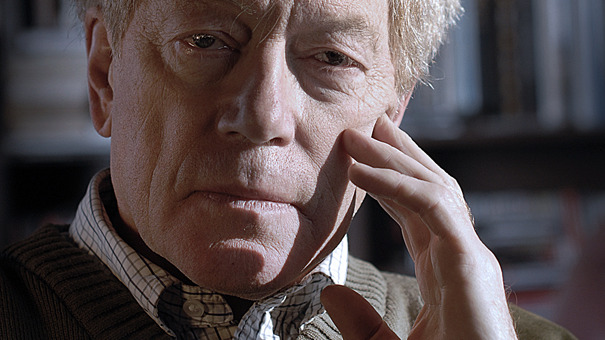

After Sir Roger Scruton’s death, it was written about him that he was a profound but controversial thinker. Well, shallow thinkers, including philosophers, are indeed usually not controversial because avoiding at all costs theses that might be controversial inevitably leads to shallow thought. Roger Scruton’s controversiality was not only because he was uncompromising in proclaiming his views and extremely intellectually courageous in formulating them but also because these views were conservative. He became a conservative in his youth, impressed by the scenes he could observe during the 1968 student riots in Paris when the government of the “fascist” General de Gaulle was being fought. He went to an ideological war in which he had to be defeated, at least for the foreseeable future. From elsewhere, it would seem there could hardly be a better place in Europe to preach conservative views, to practise a conservative political philosophy than Britain, the country of Evelyn Waugh and P.G. Wodehouse, the country where, after all, the Conservative Party had such enormous influence and where, from 1979 to 1987, the “Iron Lady”, Margaret Thatcher, was Prime Minister.

But Scruton, although he rotated in these circles and founded a philosophical discussion group that included politicians alongside journalists and philosophers, remained a “dissident” in this environment too. Above all, because he was an intellectual and British Conservatives treated and do treat all theories with great scepticism, feeling absolutely no need for “abstract” philosophy or theory.

Besides, the ideas Scruton formulated then differed from the Conservative Party ideology of the time. He was not a Thatcher-style “neo-conservative”, nor was he a radical advocate of the free market, which was then - influenced by reading Hayek or Milton Freedman, among others - also becoming fashionable in Poland. Although he spoke out against a planned economy in favour of economic freedom, in favour of the freedom of the individual, he did not believe that human ties could be reduced to mere contracts or agreements between individuals. What mattered to him was tradition, community, the endangered English identity, the authority of ancient institutions, public space, not the support of big business, the application of free market principles to an increasing number of spheres of social life or the privatisation of everything common. This kind of conservatism was even, to some extent, compatible with traditional British socialism, as demonstrated in Jack Scruton’s evocative portrait of his father[1].

Eventually, after a failed attempt to enter politics, instead of becoming an “intellectual Conservative”, he became a “conservative intellectual”. And as he stated years later: “This was an even worse idea. Ardent conservatives are acceptable in politics, but not in the intellectual world”[2]. And indeed, the books What Conservatism Means, Thinkers of the New Left, Desire, and articles in the Salisbury Review and The Times cost him his academic position and made him an institutional wanderer.

The Economist, in an obituary dedicated to him, referring to his hunting passions, compares his life to the fate of a fox chased on horseback (with an allusion also to the colour of his hair with which he had many problems as a child). Although he had a circle of devoted friends and many allies, throughout his life, he also had to deal with a witch-hunt – with trials, media attacks and moral and intellectual disqualification[3]. Even in the last year before his death, he was attacked and, for a time, removed from the Government Commission on Architecture for words quoted in an article in the New Statesman that appeared to have been taken out of context and distorted. He was aware he was also hitting hard at the left: “No doubt I have frequently been driven, in my exasperation, to lapse from accepted standards of literary politeness. But what of that? Politeness is no more than a ‘bourgeois’ virtue, a pale reflection of the ‘rule of law’ which is the guarantee of bourgeois domination. In engaging with the left one engages not with a disputant but with a self-declared enemy”[4]. The second, thoroughly reworked edition of the book on the “thinkers of the new left”, which appeared years later, is bluntly titled Fools, Frauds and Firebrands.

While he fought against the thinkers of the left, he by no means disparaged them. “No political thinker in the present state of Europe and America can ignore the changes imposed on our intellectual life by left-wing writers and activists”[5].

His conservatism was not a simple rejection of contemporary philosophy or art as nonsense, as unworthy of the West. He was not guided by the reflex of repulsion, which allows any new, fashionable idea or current problem to be treated as an invention or nonsense of “leftism”. He did not think, for example, that nature conservation was an idiocy or that it was impossible to love animals, but only that it had to be done in the right way and that this right way came from the right conservative attitude to the world[6].

He appreciated the talent of at least some of his opponents. Even in the texts of those “fools, frauds and firebrands”, whom he treated so brusquely, he can read something interesting. Of Sartre’s Being and Nothingness, a book almost forgotten today, he writes that it is “a great work of post-Christian theology” whose theme is “annihilation and sacrifice”[7]. He writes about Michel Foucault that he is brilliant, and his analyses are fascinating[8], of John Rawls that he has masterfully articulated the liberal-left conception of the state as the distributor of goods. In his essays, he refers to Freud and even Adorno.

He also valued modernism in art, in its early phase:

The early modernists – Stravinsky and Schoenberg in music, Eliot and Pound in poetry, Matisse in painting and Loos in architecture – were united in the belief that popular taste had become corrupted, that sentimentality, banality and kitsch had invaded the various spheres of art and eclipsed their messages. (…) Modernism was the attempt to rescue the sincere, the truthful, the arduously achieved from the plague of fake emotion. No one can doubt that the early modernists succeeded in this enterprise, endowing us with works of art that keep the human spirit alive in the new circumstances of modernity, and which establish continuity with the great traditions of our culture[9].

He wrote a lot. A great deal. He often joked about it himself, claiming that he always wrote the same thing, wrote the same book repeatedly, and repeated the same message over and over again. Many of these books are aimed at a wide audience. This was linked to the fact that he made his living by the pen. Since he had to give up his professorship at Birkbeck College, he had no regular employment. But this was also because the books were intended to have a pedagogical aspect, to educate people about a proper way of life. For Roger, philosophy was not an academic occupation, an art for art’s sake, a pure theory, a profession, but, as it was at its origins, a study of right living. I do not suppose that he ever published an article in a “high-scored” philosophical journal, so also from the point of view of the rules governing Polish academic life, he would have been an example of a complete failure.

He was involved in three areas of philosophy - political philosophy, aesthetics, and ethics. He also wrote, as is well known, novels and even operas. And even his fiercest opponents appreciated his texts on architecture and music. The sense of form and style he expressed in them also applied to social and political life, including his own life, which he consciously shaped according to his political, aesthetic, and moral convictions. He was characterised by that kind of snobbery which appears in the pages of the first volumes of In Search of Lost Time and which led him to see in the English aristocracy, or rather in its modest remnants in many respects, the only true elite, the depository of English traditions. It was in the aristocracy that he found that habitus, the kind of life that he wanted to cultivate and which, according to him, best expressed the essence of England.

Coming from a very humble family, he worked to achieve this ideal. He was by no means characterised by petit bourgeois elegance or neatness but by far-reaching carelessness, combined - one may say - with a typically English eccentricity and flippancy, although he was by nature a shy person. The title of knighthood, which he received a few years ago, was the crowning achievement of this work of making a style for himself, fitting him like a glove afterwards.

I knew him at a time when he was just becoming such a Roger Scruton. He had just perfected his horse riding, still having a lot of trouble putting on his harness properly, had just learned to dance, and had not yet hunted. By his example, he suggested that conservative thought has little credibility without a conservative lifestyle. Since Scruton, it has been known (also in Poland) that a true conservative thinker should live in the countryside, hate the metropolis, distance himself from fashions, be familiar with wine and cigars, like opera, and be a gourmet. Few, however, went so far as to chase a fox on horseback like him, leaping over high hedges and risking a broken neck or at least a serious fracture. Unlike many Conservative thinkers, he was not gloomy in manner. In his book Uses of Pessimism, in which he derides over-optimism and utopian illusions of left-wing thinking while recommending an appropriate dose of pessimism, he also warns against its excess:

Utter pessimists, whose pessimism deprives the world of its joyful aspect, who do not allow anything to cheer them up, not even the prospect of their ultimate annihilation, are unpleasant characters - to others and to themselves. By contrast, genuinely cheerful people, who love life and are grateful for its gift, are in great need of pessimism. In doses small enough to make it fit for consumption, but strong enough to strike at the follies that surround them and which, without it, would poison their joys[10].

And in another place, he states:

A civilization which cannot laugh at itself – like Islamic civilization today – is dangerous, since it lacks the principal way in which people come to terms with their own imperfection[11].

Among the unique characteristics of Western civilisation, he pointed to irony, which he saw even in Christianity.

2. Roger in Warsaw

He came to Warsaw in the spring of 1983, turning up quite unexpectedly at Krzysztof Michalski’s flat, where I was staying at the time[12]. They knew each other from the Institute of Human Sciences, which Krzysztof had begun to direct. Officially founded in 1982 in Vienna, thanks to the support of Pope John Paul II, as well as the then vice-mayor of Vienna, Erhard Busk, the Institute had grown out of the Dubrovnik meetings and was to be a place for dialogue between the two parts of Europe, clearly divided by the already rusting Iron Curtain. It was also meant to be a conservative institute. The first conference of the Institute of Human Sciences took place on 17-21 February 1983 and was dedicated to Karol Szymanowski. The volume Karol Szymanowski in seiner Zeit, whose editors were - besides Roger Scruton - Michal Bristiger and Petra Weber-Bockholdt, included articles by Henryk Krzeczkowski, Jan Błoński, Jacek Woźniakowski and Mieczysław Tomaszewski, among others[13]. In his article Between Decadence and Barbarism. The Music of Szymanowski, Roger compares the music of Scriabin and Szymanowski, clearly underestimating the Polish composer and concluding his essay with the sharp statement that “Szymanowski’s journey from decadence to barbarism is through a wonderful period of civilisation”[14].

Unfortunately, Roger’s collaboration with the Institute came to an end rather quickly, under pressure from the likes of Alan Ryan, a professor of political science at Oxford, in whose eyes he was unacceptable as a “fascist”, “racist” and so on. Krzysztof Michalski quickly realised that if the Institute was to have a chance for development and grants, it had to disassociate itself from such people.

Around this time, Roger set up the Jagiellonian Trust on the model of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation, which had already been active in Oxford for some years and supported Czech independent intellectuals. The board of the Jagiellonian Trust at the time also included Agnieszka Kołakowska, Jessica Douglas-Home, Baroness Caroline Cox, Timothy Garton Ash, Dennis O’Keeffe, and collaborators David J. Levy, Harold James, John Skorupski, among others. The Trust supplied us with books, and people associated with it came to give talks and lectures held in private homes.

We met again in Vienna when I stayed at the Institute of Human Sciences for two years and in London, where I was invited by the Jagiellonian Trust for my first month-long stay in the UK in 1985. Roger and his colleagues also came to officially organised conferences in Poland, e.g. a conference on Max Weber in 1985, organised by the Institute of Sociology of the University of Warsaw, and a large conference in Mrągowo at the end of the 1980s, probably in 1988. At the same time, in the late 1980s, Roger used to attend meetings of the “Cultural Attic”, organised by Marek Kuchciński. We also met at the Polish-Hungarian conference I co-organised in Vienna, “Wandel und Reformen in osteuropäischen Ländern”, in May 1987 and during my stays in Oxford, Cambridge and Edinburgh. From the second half of the 1990s, when I mainly lived in Germany, contacts loosened considerably, and we saw each other sporadically and casually - in Washington at the American Enterprise Institute, in Krakow at a conference on “Totalitarianism and the Western Tradition”, organised by the Centre for Political Thought in 2004, and in Brussels at a conference on the legacy of Solidarity, organised by the John Paul II Centre in 2014. A chance meeting in Princeton in 2013, when riding my bicycle on the campus I almost bumped into him, is particularly memorable. The last time we saw each other was at the “Poland the Great Project” congress, during a ceremony of awarding him the “Courage and Credibility” medal and in London at a reception organised by the European Conservatives and Reformists party in 2018.

Roger regarded some of my intellectual fascinations with far-reaching detachment. I remember him looking with reluctance at my book The Collapse of the Idea of Progress, stating that there was too much Habermas in it. At the time, he valued neither phenomenology nor hermeneutics nor the German philosophical anthropology in which our mutual friend David Levy was so interested. In those days, he treated the German philosophical tradition with Anglo-Saxon flippancy, making an exception for Kant and - in part - Hegel (in his autobiography, however, he confessed that one of the critical readings of his youth was Spengler’s The Decline of the West). In his later books, however, it is clear how much he draws precisely on German culture and philosophy. Some rather unexpected names appear in it. For example, he alludes to Husserl and his notion of Lebenswelt, to intentionality, refers to the hermeneutic theory of Verstehen, to Dilthey, offers phenomenological descriptions of the face, the kiss, the smile, erotic relations, and so on. One could say that, like Józef Tischner, whom he knew from his Viennese days, he practised a phenomenology of the “human drama”. He was never convinced by Habermas, although human communication becomes a central subject of his reflections.

He was a great admirer of the arch-German Wagner, to whom he devoted two books and to whom he often referred. Even when he wanted to explain the Christian idea of the incarnation, he surprisingly referred precisely to Wagner, inverting the meaning of Christian love for a moment.

The [Nibelung] Ring can be understood as an attempt to show, through artistic rather than intellectual means, the deep connection between freedom and suffering. It is in terms of this connection that we understand the highest form of love – the love in which giving is total. If God is to enjoy that love, and the redemption that is innate within it, the implication is, then he too must be incarnate in mortal form. Love belongs to the human condition, and God becomes a complete object of love by accepting that condition as his own[15].

3. The struggle on the periphery

Why were Roger and his friends interested in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe?

There was a certain element of adventure, and thrill, all the more pleasant because, after all, without the not-very-exciting consequences that threatened us, the inhabitants of this region. So one could say, paraphrasing Krasicki’s phrase, that for them, it was a “game”, an antidote to the English spleen, while for us, it was “about life”. But that would not be a fair judgement, something we did not fully realise at the time: to them, too, it was about life, about preserving this world which, they were convinced, was fading before their eyes under the influence of radical trends in culture, philosophy, art. For Roger, the socio-political system of communism was not the result of the backwardness of Central and Eastern Europe, nor was it an Asian barbarism, nor even a product of Russian despotism, but the political and social embodiment of the left-wing ideas propounded by his colleagues at Oxford, Cambridge, London, or Berkeley.

In Thinkers of the New Left, he wrote: “The inhuman politics of communism is the objective realisation of the Marxist vision of society, which sees true politics as no more than a mendacious covering placed over the realities of power”[16]. While supporting the Czechs, Poles, and Romanians, he was also fighting for himself, for his reasons, with his opponents and enemies, for Britain, the United Kingdom, and Western civilisation. It was here, in Poland or the Czech Republic, that he reasserted his right to fight Marxism and the new Marxist left. Resistance against communism was to be resistance in the name of sacred conservative values, a true conservative counter-revolution. This was all the more important because it was the workers who were fighting for their rights, disavowing the Marxist and left-wing narrative. In communist-controlled Central and Eastern Europe, conservatism was transforming from nurturing and perpetuating existing institutions and customs into a subversive doctrine.

Paradoxically, it was a time of exceptional freedom of thought, despite external repressions, despite martial law. There was a yearning for books, ideas, and intellectual exchange with the Western world. Conservatism was by no means something negatively perceived. This is why, unlike in the “West”, Roger was listened to willingly and with interest, regardless of one’s views - also at the aforementioned, officially organised conferences, which were also attended by members of the Polish United Workers’ Party.

While in the “West” someone considered “right-wing” was not treated in intellectual circles as an opponent but as a disease symptom that had to be eliminated, in Poland, in the era of the communism’s collapse, it was no longer appropriate to be “left-wing”, to concede to Marxism. Slowly such self-definition was becoming compromising. External observers were struck by a fact characteristic of Poland at the time, i.e. while those with right-wing or conservative views openly declared them, those with left-wing views avoided clear political identification, claiming they were “neither right-wing nor left-wing”.

It was with a certain naivety that we looked at Western culture and societies at the time. The “West” was the model and the ideal, and only diminishing groups of lagging party orthodoxies still warned against imperialism and decadence. The majority, however, treated everything that flowed from the “West” as attractive ideas of freedom, more or less overtly directed against communism[17]. Therefore, cultural contestation may have led to conservative attitudes and views in the future. As is well known, some participants in the hippie movement in Poland today are leading politicians of “Law and Justice”. The dilemmas of the “West” were not yet our concern, and Marxism in Western universities was, for some, a useful bridge to their own international careers; for others, a quirk resulting from ignorance and blindness. Negative phenomena were noted, but without emotion, as essentially insignificant margins. In the end, after all, it was all about being like the “West”, even with its faults or foibles. The disputes there seemed secondary and without serious life consequences. I have to admit that it was only the ruthlessness with which Roger was eliminated from participation in the Institute’s projects and later pushed to the margins of academic life that made me realise it was not only in “real socialism” that one pays a huge price for one’s views, but also in the “West”, and that the liberal democracy that prevails there does not necessarily mean freedom of thought. Today we clearly realise that, as Roger wrote years later: “The inescapable conclusion is that subjectivity, relativity, and irrationalism are advocated not in order to let in all opinions, but precisely so as to exclude the opinions of people who believe in old authorities and objective truths”[18].

Today, the European left pretends that communism - real socialism - had nothing to do with the contemporary left - old and new - and it with it. After a period of confusion, disorientation and panic in left-wing circles in the 1990s, after the creative deconstruction of old left-wing dogmas as a result of the healing shock of the collapse of communism, a new left-wing orthodoxy was consolidated, this time mainly appearing under the banners of liberalism rather than Marxism, and the fight against “fascism” began again, which could be, for example, scepticism about European integration, attachment to family and nation, understanding gender as a biological fact or rejection of a multicultural model of society.

4. Conservatism versus liberalism

It was politics and political philosophy, not aesthetics that interested us most in Scruton’s publications at the time. Of course, there were many reasons why the pursuit of beauty, for Roger an inalienable but endangered aesthetic category, stood in the background in Poland.

Beauty would be needed because the Polish People’s Republic was appallingly ugly. Yes, magnificent works of art were created - often much better than those created in the Third Republic - but the experience of everyday life, the architecture of the blocks of flats in which we resided, and the devastated environment in which we lived did not create hope that anything could be made beautiful without overturning the entire political and social order.

It was, therefore, not beauty that was our main concern but freedom, civil rights, and democracy. It was, therefore, not the aesthetics that interested us most but political philosophy and arguments against the ever-present state doctrine. It was a struggle from which – according to the beliefs of the time – a space was yet to emerge where “normal” – that is, such as in the “West” – political differences between left and right, liberals and conservatives would be possible, but also the possibility of realizing such values as beauty would be restored.

After communism, however, liberalism was to come, not conservatism[19]. After 1989, advice was expected not from Roger Scruton and John Paul II, but from Jeffrey Sacks and Leszek Balcerowicz, with Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan as idols.

From the outset, the interpretation of conservatism proposed by Scruton was not only directed against the new left - it was also a polemic against liberalism, although this did not mean, as he claimed, its outright rejection. In The Meaning of Conservatism, however, he states that “real existing liberalism” is a relative of “real existing socialism”[20]. Conservatives are guided by a natural pietism, respect, and reverence for established institutions, customs, and faith, whereas liberals, based on a radical understanding of the principle of individual autonomy, appeal to abstract justice, human rights, which necessarily leads to a revision of existing institutions, which are measured by universal standards and reformed according to them. Liberalism universalises the “first-person perspective”, whereas conservatism always sees the individual as situated in a cultural and social context that precedes and shapes the individual’s identity.

In all its variants and at every level, liberalism embodies the question, “Why should I do that?” The question is asked of political institutions, of legal codes, of social codes - even of morality. And to the extent that no answer is forthcoming which proves satisfactory to the first-person perspective, to that extent are we licensed to initiate change[21].

Liberalism - as Scruton notes, paraphrasing Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde’s well-known thesis - reveals a fundamental paradox: it is doomed to undermine the conditions that make it possible[22]. These conditions are institutions, customs, norms, and cultural patterns that are sustained through the obedience and loyalty of individuals. Scruton was never an advocate of the idea of a “minimal” state, nor did he believe that it could be confined to its role as a collector of taxes and distributor of wealth, a collective benefactor. As he argued, the state grows out of social life, it is the self-organisation of the people, and conservatives, he wrote, cannot be about freedom from government, from the state, but about a better government, a better understanding and action of the state[23].

5. Two worlds in one

Roger, whom I knew as a non-believer, though who as a conservative recognised the importance of religion for social life, devoted much attention in his later books to religious experience, the understanding of God and the importance of the Church. His three books The Face of God, Human Nature and the most systematic and interesting The Soul of the World, are essentially variations on the same theme, parts of the same work, with recurring and complementary motifs.

It is a return to ancestral faith for him, as can be seen in Gentle Regrets and in his book on the Anglican Church - Our Church. A Personal History.

But it is also linked to a new challenge that was not seen or felt in the 1980s and even the 1990s. He states that “the defence of Western civilisation is less a matter of resisting native resentment and socialist projects of distributive justice than of resisting an armed and indoctrinated adversary in the form of radical Islamism”[24]. Elsewhere, he adds that the issue of the secular state’s Christian roots and religion’s place in a society based on the principle of freedom of conscience is being revisited in relation to Islam[25].

However, the triptych mentioned above is primarily about how faith and science can be reconciled and how religion can survive in a world dominated by scientific cognition.

In seeking an answer to the question about the place of spirituality in our civilisation, unlike many conservative thinkers, he does not go back to pre-modern times, to pre-Cartesian and pre-Kantian philosophy; he does not seek the right way of living and thinking in ancient Greece - like Martin Heidegger, Leo Strauss, or Ryszard Legutko - but in modern philosophy, accepting its turn towards consciousness and the subject.

He did not think it was possible to renew metaphysics as a general reflection on being. His “proof of the existence of God” - or rather, the hypothesis or mere suggestion of existence - resembles that of Robert Spaemann: it starts from the notion of a person rather than from a reflection on the world or existence. “We can”, he argues, “reconcile the God of the philosophers with the God who is worshipped and prayed to by the ordinary believer, provided we see that this God is understood not through metaphysical speculations concerning the ground of being, but through communion with our fellow humans”[26]. The idea of a personal God emerges, as it were, “naturally” from the experience of another human, another person. But Scruton seems to think that the opposite is also true, and the loss of the idea of God would have to lead to a violation of intersubjectivity, of people understanding each other as persons.

The next steps of his argument lead from self-consciousness and the notion of person to intersubjectivity, to the “we” - the “first person plural” - from which he derives experience and the notion of God. He goes back to Kant and Thomas Nagel in explaining the notion of self and person, to Hegel in analysing interaction, to Husserl for the notion of Lebenswelt as a non-scientific way of experiencing the world, to Émile Durkheim and René Girard to explain the origin and essence of religion.

Rejecting scientism and arguing (with reference to examples from music and painting) that the phenomenon of self-consciousness and the human person cannot be explained and described in a naturalistic, materialistic way, he develops the thesis of the cognitive dualism of the world. In contrast to Husserl, the “lived world” is not, according to him, the forgotten, primordial foundation of science, but only another, equivalent way of experiencing the world, irreducible to scientific cognition, incompatible with it.

However, religion cannot be reduced to the experience of the individual either; it is a communal cult: “Religion therefore begins in the experience of community, and in the desire to be reconciled with those who judge us and on whose love we depend”[27].

In the lived world, we experience the sacred, the sacred things. Among other things, this is when we deal with the body of the dead:

In dealing with the dead body, we are in some way standing at the horizon of our world, in direct but ineffable contact with that which does not belong to it. That, I venture to suggest, is the essence of the sacred. And the experience of the sacred needs no theological commentary in order to invade us. It is, in some way, a primitive experience, as basic as pain, fear or exultation, awaiting a theological commentary perhaps, but in itself the inevitable precipitation of self-consciousness, which compels us to live forever on the edge of things, present in the world, but also apart from it[28].

This is not, however, a philosophy of joyful optimism. Man, being a dual being - a thing among things, an animal, and a self-conscious person - is a torn and lonely being. Self-consciousness results in separation from the world and existential loneliness.

Human beings suffer from loneliness in every circumstance of their earthly lives. (…) The separation between the self-conscious being and his world is not to be overcome by any natural process. It is a supernatural defect, which can be remedied only by grace[29].

And civilisation is fragile:

Human life is conducted on a thin crust of normality, in which mutual respect maintains a general equilibrium between people. Beneath this thin crust is a dark sea of instincts, quiescent for the most part, but sometimes erupting in a show of violence. Above it is the light-filled air of thought and imagination, into which our sympathies expand and which we people with our visions of human value[30].

He adds, however, that these spiritual forces are powerless in the extreme.

But when the eruptions come it can do nothing to tame the violence. Nor can religion do anything, nor can ordinary morality[31].

6. Culture - the successor of religion

Reclaiming his religion for himself, Scruton sees that it has almost completely died in the surrounding world. Its substitute is culture - I think for a long time, it was for him too.

Art has gradually taken over from religion the task of symbolizing the spiritual realities that elude the reach of science. In this way, as religion has lost its hold over the collective imagination, culture has come to seem increasingly important, being the most reliable channel through which exalted ethical ideas can enter the minds of sceptical people[32].

Still, culture, though now detached from religion, continues to contain the content that religion once conveyed: “neither the elite culture nor popular entertainment belong to the practice of religion, but (…) both, in secret or not-so-secret ways, bear the impress of religion”[33].

For him, culture is a treasure trove of affective knowledge that allows us to understand others, to maintain intersubjectivity: “We ‘rehearse’ our sympathies through our encounter with fictions, and so come to ‘know what to feel’ in situations that we have not previously encountered”[34].

And elsewhere, he adds: “Culture inherits from religion the ‘knowledge of the heart’ whose essence is sympathy. But it can be passed and enhanced, even when the religion that first engendered it has died”[35].

But the end of religion in Western civilisation is also followed by the end of art. Works of art in museums are increasingly “votive offerings of some dead religion”[36]. Moreover, artists undertake desacralisation, desecration of the sacred, profanation of symbols, and violation of norms. In fear of kitsch, contemporary art serves destruction in the name of freedom - often producing kitsch anyway.

Writing about rays of hope, he sees them in the renaissance of tonality in music, in the “healing of the eye” by certain painters and architects:

The artistic and intellectual traditions of our culture are alive in the novels of Ian McEwan and Michel Houellebecq, in the philosophy of Alain Finkielkraut and Luc Ferry, in the plays of Tom Stoppard and Alan Bennett, in the poetry of Charles Tomlinson, Rosanna Warren, and Ruth Padel, in the work of freelance historians like Paul Johnson and Gertrude Himmelfarb, and of freelance critics like Norman Podhoretz and James Wood[37].

Elsewhere, he mentions composers like Henri Dutilleux and James MacMillan, painters like David Inshaw and John Wonnacott, novelists like Italo Calvino and Georges Perec, architects like Quinlan Terry and Liam O'Connor[38] as well as “rescuers of the Judeo-Christian legacy” artists and thinkers from Central and Eastern Europe and Russia: Jan Patočka, Milan Kundera, Václav Havel, Czesław Miłosz, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn[39].

7. Our abnormal normality

Colleagues and friends from the Jagiellonian Trust came to see Poland in the 1980s as a country where, beneath the cracking shell of communist ideology and power structures, they saw Poland pulsating with tradition. I remember Dennis O’Keeffe’s surprise, observing the faithful in the Church of the Holy Cross: “Here everyone believes,” he said, “Even the priests”.

Today, they come to a free country where a socially conservative party is in power, where conservative ideas are present in the public space and influence - as much as possible - politics, influence government action. Unlike in the case of the British Conservative Party, in the circles of politicians associated with “Law and Justice”, ideas also count, not just pragmatic interests.

However, as we know, this is a government contested by academic and cultural elites. Roger’s books and essays, analysing contemporary music, painting, architecture, and theatre, help us understand why this conflict is inevitable. They make us realise that it has a deeper basis than purely political or social divisions. It is a dispute about the whole, philosophy, and understanding of man and his place in the world.

We do not know how this dispute will be resolved, but the term “right-wing” is still not a stigma in Poland that de facto excludes people from public life, as it is, for example, in Germany. Nevertheless, intellectual Poland resembles the world Scruton described in Thinkers of the Left more than it did at the end of the communist era. It is characteristic that no Polish university has awarded him an honorary doctorate. And only once, as far as I know, has he been invited to lecture at a university in recent years.

The Polish academic world, meanwhile, has become similar to British, French, or German academic institutions - not in terms of technical skills or originality of thought, but in terms of ideology. In our country, too, numerous “women sociologists” and sociologists, “women philosophers” and philosophers, and other humanists use a well-binding post-Marxist jargon that cannot be imitated, only that instead of the proletariat other subjects of the revolution are now perceived, which, emancipating themselves from the state of deprivation, liberate the whole of humanity, regardless of whether it wishes it or not.

The elegy dedicated to England and Scruton’s description of his own “homecoming” in his late work are moving because they show it to be a largely desolate home. It is clear from his description that while there is much more continuity in the material culture of England than in Poland, spiritually it is still perhaps the other way around. Scruton writes that almost nothing remains of the norms, patterns, ideals, customs, and cultural aspirations of his childhood. Poland, despite communism and imitative modernisation, is still a less devastated country than England[40]. In Poland, one can still encounter lively communities of believers and priests who believe, and the society is still neither “multicultural”, which inevitably entails relativisation, nor “progressive” enough to meekly accept a fundamental revolution in customs and loss of identity.

In a beautiful essay on how to properly experience mourning, Roger analyses Metamorphoses, Richard Strauss’s work of mourning for an irretrievably lost Germany, the one before the Third Reich, which could never be the same again after it. He compares it to his book on England, which is intended as an elegy. “Elegies are attempts at reconciliation and redemption. (...) Strauss’s Metamorphosen is not, in that sense an elegy. It is a work de profundis, which looks back to what has been lost as the returning traveller looks at the bombed out remnants of his city, in which not a survivor can be found”[41]. He never lost hope that, as far as England was concerned, all was not lost[42].

There were moments of doubt for him. Writing about the disappearance of the sacred and consumer culture in which everything becomes an object of desire and exchange, he concludes that „our disenchanted life is, to use the Socratic idiom, ‘not a life for a human being’”[43]. But contrary to those who repeat Adorno’s trivialised words that es gibt kein richtiges Leben im falschen, Roger’s essays contain recommendations on how to live as one should in such a world. And not just live. In his essay Dying in Time, he advises that in old age one should not spare one’s body, engage in risky types of sport, not worry about a healthy lifestyle and diet, but try to keep one’s mind fit by forming incisive opinions that allow one to win friends by enjoying friendship, and enemies whose attacks are a stimulus to thought[44]. This is how he died. Like a philosopher.

Bibliography

Bristiger M., Scruton R., Weber-Bockholdt P. (Hrgs.) (1984), Karol Szymanowski in seiner Zeit, München: Wilhelm Fink.

Jawłowska A. (1975), Drogi kontrkultury, Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

Legutko R. (2008), Esej o duszy polskiej, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka.

Scruton R. (1984), The Meaning of Conservatism, Second edition, London: Macmillan.

Scruton R. (1985), Thinkers of the New Left, Harlow: Longman.

Scruton R. (2006), Gentle Regrets. Thoughts from a Life, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Scruton R. (2010a), Kultura jest ważna. Wiara i uczucie w osaczonym świecie, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka.

Scruton R. (2010b), The Uses of Pessimism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scruton R. (2014), The Soul of the World, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Scruton R. (2015), Oblicze Boga. Wykłady imienia Gifforda 2010, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka.

Scruton R. (2016), Confessions of a Heretic, Honiton: Notting Hill Edition.

Scruton R. (2017a), Conservatism. An Invitation to the Great Tradition, New York: Horsell’s Morsels.

Scruton R. (2017b), Zielona filozofia. Jak poważnie myśleć o naszej planecie, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka.

Szacki J. (1994), Liberalizm po komunizmie, Kraków: Znak.

Wencel W. (2010), De profundis, Kraków: Arcana.

Wildstein B. (2015), Cienie moich czasów, Poznań: Zysk i S-ka.

[1] Vide Scruton 2006.

[2] Scruton 2006, Kindle Edition, Location 833.

[3] He describes this in detail in Gentle Regrets (Scruton 2006).

[4] Scruton 1985, p. 211.

[5] Scruton 1985, p. 1.

[6] Scruton 2017; Scruton 2016, p. 18–33.

[7] Scruton 2014, p. 188.

[8] Scruton 1985, p. 37.

[9] Scruton 2016, p. 5.

[10] Scruton 2010b, p. 166.

[11] Scruton 2010a, p. 48.

[12] As he recalls in one of the interviews, talking about his activities in Czecho-Slovakia: „I came from Poland. And in 1979 Poland was kind of fomenting, because of the election of the pope, the election of Karol Wojtyla to the throne of St. Peter. There was the Polish pope, they had this revival of religious feeling, a sense that something was changing, the ground was beginning to tremble. So coming from there I came as though already animated by the sense that something might change. But of course the immediate effect stepping off the train from Krakow at the Main Train Station here was of total silence”, https://www.vhlf.org/havel- conversations/seeing-former-underground-students-enter-politics-post-1989-was-wonderful- says-philosopher-roger-scruton/

[13] Bristiger, Scruton, Weber-Bockholdt 1984.

[14] Bristiger, Scruton, Weber-Bockholdt 1984, p. 159–178, quote p. 173.

[15] Scruton 2015, p. 160.

[16] Scruton 1985, p. 209.

[17] Cf. Jawłowska 1975.

[18] Scruton 2010a, p. 82.

[19] Cf. Szacki 1994.

[20] Scruton 1984, p. 198.

[21] Scruton 1984, p. 196.

[22] Scruton 1984, p. 203.

[23] Scruton 2016, p. 49.

[24] Scruton 2017, p. 148.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Scruton 2015, p. 25-26.

[27] Scruton 2015, p. 144.

[28] Scruton 2015, p. 150.

[29] Scruton 2015, p. 142.

[30] Scruton 2010a, p. 42.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Scruton 2010a, p. 26.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Scruton 2010a, p. 51.

[35] Scruton 2010a, p. 41.

[36] Scruton 2010a, p. 87.

[37] Scruton 2010a, p. 89.

[38] Scruton 2016, p. 16 i 68.

[39] Scruton 2010a, p. 88.

[40] It would be interesting to compare Scruton’s experiences with Ryszard Legutko’s Esej o duszy polskiej and Bronisław Wildstein’s Cienie moich czasów, in which the latter describes his life path – from political and social rebellion to affirmation.

[41] This is probably how Wojciech Wencel looked at Poland in his excellent volume of poetry De Profundis, published in the memorable year 2010.

[42] Scruton 2016, p. 119.

[43] Scruton 2015, p. 162.

[44] Cf. Scruton 2016, p. 150.

This text was originally published in Polish in Przegląd Filozoficzny (Philosophical Review) - New Series R. 29: 2020, No. 1 (113), ISSN 1230-1493 DOI: 10.24425/pfns.2020.132967

Read also

Seen From Warsaw, Seen From Brussels: The Final Report

What does not understand Poland's situation are those – or they simply do not care about Poland – who think that there is no problem at all, that the European Union always acts in accordance with our interests and values, and that it is enough to implement its regulations and directives.

Zdzisław Krasnodębski

Seminarium pt. "Wiara i rozum w naszych czasach"

Seminarium Stowarzyszenia Twórców dla Rzeczypospolitej

Comments (0)