Freedom of Speech in Western Civilisation[1]

1. The subject is difficult because it touches on the idea of freedom. And this idea in itself harbours antinomies that are not easy to resolve.

When one grants freedom of speech without restricting it in any way, one also allows for the possibility of its misuse - for example, the spread of erroneous, harmful, or perhaps even destructive views. Contrary to the principle that good begets only good, here it is as if the opposite were the case: from the good of freedom, the evil of its abuse arises. This is the objective side of the antinomy. And with it is associated the subjective one: by granting freedom, we consent beforehand to the evil of its misuse and thus become complicit in it. It is justifiable to accuse us then: “If you had not let them speak nonsense, they would not have caused harm”.

Let us take an example. We all remember the recent horrific incidents at a construction technical school in Toruń, where pupils abused their English teacher, verbally insulting and physically humiliating him during their classes. Among many other people on the matter spoke Jacek Kuroń, a fairly well-known figure. Here are his words:

When I read the report about the incident at the Toruń Technical School, my first thought was: truth be told, the situation had not worsened but improved. Because before, the power was solely on one side - teachers ruthlessly persecuted students. Now, a certain balance of power has emerged - both students and teachers are being crushed.[2]

Man – one would want to exclaim – do you even understand what you are saying? This is precisely the subjective aspect of our antinomy: to allow such verbal outbursts or not to allow them? By allowing, we ourselves contribute to the destruction of the school. By not allowing, we ourselves undermine freedom of speech. So bad and not good either.

2. In the Western world today - from Vilnius to San Francisco - a fierce political battle is being fought over the spiritual shape of our civilisation. Two conflicting aspirations are clashing within it: on one hand, unbridled libertarianism, and on the other, Christian morality. The libertarian feels the restraints inherent in this morality as an unbearable limitation of his “subjectivity”. And this “subjectivity” - such as “self-realisation”, “individual creation of values”, and similar lofty words - are merely synonyms for debauchery.

Here is news from the frontline of this struggle, one of a thousand. The press has just reported that permanent police posts have been introduced in thirty Warsaw schools, and by the end of the year, there are supposed to be 250 of them (“Rzeczpospolita”, 13.1.2004). What we have here is blatant proof of the complete bankruptcy of libertarian pedagogy. It was, in fact, easy to predict. First, the teacher’s authority was destroyed, and then gangs of youth, both in and out of school, began to take control in schools. Now, the police are being introduced into schools to restore some order. Libertarian upbringing is a straightforward path to police upbringing. Alarm sirens should be wailing, yet instead, a little note is placed on the tenth page, insouciant in tone.[3]

Libertarianism is on the offensive and seems to be taking over. (Although it still claims to be oppressed). This offensive threatens our entire civilisation and disintegrates its support structure. Therefore, let us become aware of this civilisation’s essence: what distinguishes it from all others - past and present.

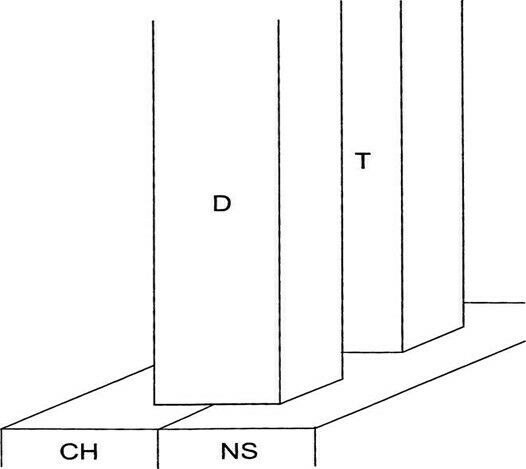

3. Western civilisation can be imagined as a grand structure consisting of two foundational pillars and two towering spires built upon them. One pillar is Christianity, and the other is the sciences. By their very nature, these foundations are less visible, as they are deeply embedded in the metaphysical soil of reality. However, both spires are prominently visible from afar. One spire is democracy, which entails respect for human beings and their civil rights. The other is technology, i.e. technology based on scientific understanding of the laws of nature. Each spire relies on these two pillars for support, as illustrated in the diagram.

It is worth noting and emphasising that the entire structure is spiritual in all four of its parts, even though each part also has its material, external aspect. Technology is not just about Boeing planes but the ability to manufacture them; democracy is not just about parliaments but the civic spirit that permeates them; the sciences are not just universities and laboratories but the investigative sense and unwavering reliability within them; and Christianity is not just temples and processions but apostolic succession - the continuity of faith and tradition through the ages, which gives life and meaning to the former. If some catastrophe were to destroy the external aspects of our civilisation while preserving the internal, we would quickly rebuild the former. However, if, conversely, a calamity were to destroy the internal, the external would collapse on its own quickly.

The pillar of Christianity is weakening and bending. Consequently, the spires supported by it are wavering. For democracy, this is clearly visible: the civic spirit is fading in the West. But it is also becoming increasingly apparent for technology, especially - as Lem says – in the face of its invasion into the human body and human nature.

Libertarians would like to replace the pillar of Christianity with a “secular humanism”: this, as a new quasi-religion, would carry forward the spiritual construction of Western civilisation. Such expectations are a pipe dream; no “humanism” can carry this construction. Nor will “humanist” pseudo-liturgy, such as the so-called “Christmas Aid Orchestra” with its shrieking sentimentalism, help. (It is precisely as a substitute for liturgy that it is so strenuously advertised).

There has been one serious attempt in history to replace Christianity as the building block of Western civilisation with another. That attempt was communism. It took off, after all, as a new Christianity. (The last work of one of its spiritual fathers, Count de Saint-Simon, even had that title). It advanced like a hurricane for a hundred years, and it seemed it would prevail. But it ended in a terrible fiasco.

I do not know whether the yielding pillar of Christianity can be strengthened. What I do know is that replacing it is an extraordinarily difficult and risky operation, perhaps even impossible.

4. The cornerstone of democracy is freedom of speech. The one is coextensive with the other: as far as democracy extends, so does freedom of speech, and where freedom of speech ends, democracy ends, too. For Western civilisation, freedom of speech is a distinctive feature, unique to it.

The model for modern democracy is the American Constitution. The First Amendment to it states briefly and clearly: “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” Does this mean - as libertarians believe - that freedom of speech is unrestricted in democracy and that any form of censorship is unacceptable? Well, no.

Democratic law is anchored in morality. Without it, it becomes a mere dummy. In America, it was Christian morality in its Puritan-Calvinist variety. This morality was the unspoken premise for this amendment and the entire Constitution. The Founding Fathers - as the Americans call them – simply could not fathom that someone would misuse that amendment for criminal or blasphemous purposes, for example, to insult the Virgin Mary with impunity[4].

Freedom of speech also means tolerance for views that are alien, even repugnant, to us. We are prepared to bear them patiently, opposing them only by persuasion - but up to a limit. There is always a range of tolerance beyond which it ends. Democracy is based on general agreement on the limits of this range and the necessity of respecting them. On this consensus lies its internal coherence, without which no community can exist.

5. What about when the word tolerance limit is overstepped? Then, it must be restored by force.

“That’s censorship!” - the libertarians will shout. Yes, because it is not the case that democracy does not allow any form of censorship. Only covert censorship, or so-called “preventive” censorship by the police, cannot exist in it. Instead, there can be overt censorship - so-called “repressive” censorship - administered not by the police but by the courts.

In a democracy, however, censorship is always a last resort, resorted to when the foundation of morality breaks down, and the boundaries set by it break. The struggle in question is precisely about where these boundaries lie.

Tolerance and its limits are best examined not in general terms but using concrete examples. Here are two particularly drastic ones.

A year ago in Gdańsk, a young woman claiming to be an “artist” profaned a crucifix in a vulgar manner. Attempts were made to bring her to justice for this - a mode of repressive censorship that democracy allows. Numerous voices of libertarian defenders were raised against this. Four rectors of the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań published an open letter in which they expressed their “utmost concern” about this act of “totalitarian pressure” and regarded the “conviction of a young artist” as “a cruel manifestation of a dark force akin to the Inquisition” (“Rzeczpospolita”, 28.7.2003). And the Speaker of the Polish Sejm, Marek Borowski, publicly declared that he would defend the right of this “artist” to her lewd acts “to the bitter end” or even “until the death”. The mentality of a libertarian is difficult to comprehend.

The second example is from January this year. Here in Stockholm, another artist came out with an “art installation” glorifying the murderous actions of Muslim terrorists. He accompanied it with the following explanation: “If our nation cannot realise its dreams and goals, let the whole world crumble to dust” (“Rzeczpospolita”, 20.1.2004). Despite a vehement protest from the Israeli ambassador, the museum’s management, which displayed the “installation”, announced that it would not take it down. And the Swedish foreign minister, who was questioned about it, declared that the management was independent and could do whatever it wanted.

What we have here are two illustrations of rampant libertarianism, insensitive to any persuasion. It can only be tamed by force - if you have it and are prepared to use it. So what to do?

6. Let us formulate the question more precisely: do we consent to a crucifix being profaned and terror glorified before our eyes with impunity, or do we not consent? It is not a legal question. Democracy is faced here with a completely new situation, not provided for by any laws or codes to date. In this case, it is not possible to refer to a law that is already in place but, on the contrary, a proper law has yet to be democratically created, resolving such precedents by an act of popular will[5].

Let us understand this well. The question “do we consent?” must first be answered by everyone individually in their conscience - and it will be their moral decision: “do I consent?”. And then all of us - and this will be our political decision - must answer this question through a vote: what kind of law do we want? This is how the boundaries of tolerance are drawn in a democracy: by precedents, which are like boundary posts being hammered in. General discussion will not solve anything here.

In setting such precedents, democracy is not hasty because it is aware of their double-edged nature. Every legal restriction on freedom of speech is fundamentally perilous for democracy as a system: it either opens – or, rather, paves - the way for further limitations. We are, therefore, faced with the need to evaluate which evil is lesser: allowing antics that undermine democracy or creating a precedent that erodes it. That is why the demand for restraint in exercising democratic freedoms, particularly freedom of speech, is so important. Those who violate this restraint damage democracy twofold: by sowing scandal and provoking repression.

The civilisational venom of libertarianism - like terrorism! - is that it forces democracy to take steps that may prove suicidal for itself. In any case, they undermine the libertarian bindings of its structure and push it either towards repression (when we agree to censorship) or anarchy (when we do not agree to censorship). It is in the interest of all citizens not to be confronted with such choices.

The march of boastful libertarianism seems unstoppable, but perhaps we are under the illusion of too short a perspective. For there are signs that a quiet opposition to it is growing in souls and that even people with rather libertarian inclinations are beginning to feel uncomfortable at the sight of its fruits[6].

When I look at this boastful parade, in which the “freedom of art” slogan serves as a hammer to shatter morality, the words from many centuries ago come to my mind. They were uttered by one of the Church Fathers to one of his Roman Emperors contemporaries - probably St Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan to Theodosius I. There was some dispute between the emperor and the bishop, and as sometimes happens with power, the emperor made threats. To this, the bishop responded: “Your Majesty, the Church is like an anvil: its task is not to strike blows but to receive them. But perhaps His Imperial Majesty would like to consider that many hammers have been worn out on this anvil”.

[1] *Lecture at the symposium “Faces of Freedom of Speech” at the University of Social and Media Culture in Toruń, 24 January 2004. Published also in Filozofia i wartości. Post Factum, Wydawnictwo Antyk, Komorów 2021.

[2] J. Wróbel, Nie bijcie w dyscyplinę, „Rzeczpospolita”, 3 November 2003.

[3] The school can do very little. It can a) impart knowledge, b) implement order and systematic work. The rest is a pedagogical utopia, contrary to human nature. And like every utopia, it must end with the police.

[4] As was recently the case in Warsaw, where the well-known motif of Christian sacred art was desecrated, reproduced 500 times with bare models. See Pieta na 1000 osób in “Rzeczpospolita”, 7 November 2003.

[5] It is not the mere profaning of a crucifix, insulting the Virgin Mary or glorifying terror that is an outrage, but the fact that one can do so with impunity. (And in general: it is not the crime itself that destroys the social moral order, but the impunity of the crime - also through the inadequacy of the possible punishment).

[6] For example, we read that as many as 77% of Poles are against libertarian legislation, advocating the restoration of the main penalty.

Read also

On the Idea of Fate

1. I want to talk about the idea of fate, not the concept or sense of it.

Comments (0)