On the Idea of Fate

[2010]

1. I want to talk about the idea of fate, not the concept or sense of it. The notion of fate is a logical question: it concerns the meaning of a word and aims at some definition, metaphysically sterile. And the sense of fate is a psychological state, suitable for psychological quandaries, metaphysically equally barren. The sense of fate is secondary to its idea: it gives rise to it, not the other way around. Today, psychology is willingly substituted for metaphysics; for example, in the philosophy of religion, they fantasise endlessly about supposed "religious experiences" or "mystical experiences". Philosophically, this is deception: a cheap substitute is passed off as a branded commodity. Philosophy is not concerned with what people imagine and think but with how things really are.

The idea of fate represents a certain metaphysical perspective: a particular point of view from which we view our lives and the world around us. This perspective exists objectively; it does not depend on us. We do not create it; we only find it. It is with this as with ordinary optical perspective. It is not my eye that creates the point of view which, according to the laws of projective geometry, determines its perspective. The eye merely enters this ready-made point of view by inserting its lens into it - just like a camera. Psychology has nothing to do here. By entering intellectually into the perspective of fate, we thereby arouse emotionally and secondarily a sense of fate, as it were.

I use the term "idea" in Kant’s sense. He would say that the idea of fate is a certain "regulative principle" (cf. Windelband II/105), organising our way of thinking about the world and life, though saying nothing concrete about them. It sets the proportions differently. In this, it is similar to the idea of infinity. The idea of infinity permeates all of mathematics, but its content cannot be satisfactorily contained in any definition. It is still best expressed, although only indirectly, by the principle of mathematical induction, that nerve of mathematical thinking.

The idea of fate is ancient. In Homer, it appears as Moirai, which originally meant "apportion": that which is "apportioned" to someone. Later, in the Greeks, another name appeared: Tyche. Originally, it meant as much as "happenchance": that which "happens to" someone. Father Bochenski (Europäische Philosophie der Gegenwart, 1951, p. 204) called tychic such a philosophy that sees and appreciates the enormous role that the element of fate plays in human life. In the idea of fate, as we are about to see, both Greek sources are preserved: Moirai and Tyche, apportion and happenstance. The two faces of fate are revealed in them.

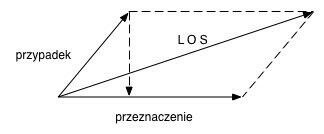

2. The idea of fate is not a simple idea. It can be divided into two simpler component ideas: the first is d e s t i n y and the second is c h a n c e. Our fate is the resultant of these two: destiny and chance - as shown in the figure.

In these components, we easily recognise both Greek ideas: "destiny" is, after all, the Greek moirai - that which fate has "apportioned" to us; and "chance" is the Greek Tyche - that which randomly "happens" to us.

Webster’s New World College Dictionary, a well-known American dictionary, very accurate in its definitions, has as its main characteristic of fate that it constitutes some agency beyond human control: some "causal agent beyond the reach of human will". Note that this can be applied to both components: neither what we are "destined" nor what is "apportioned" to us has any influence. (If we had, it would not be "fate" but our action: a manifestation of our will.) The orchestration of fate is something that comes from outside, from outside our will - as something we have to accept and go along with, willing or not. Fate does not ask what we want.

The insensitivity of fate to our desires and wishes, even the most fervent, is its first incredible trait. It can be said that in the word "fate", we express the unfathomable foreignness of the surrounding universe. From this inhuman foreignness, we are indeed shielded by the membrane of our everyday life. However, every now and then, peeking through this membrane is that something - foreign, menacing, and incomprehensible: beyond human control. And not only does it shine through, but it sometimes invades everyday reality. And then we go numb with horror and say - if we are still able to say anything, "It was a stroke of fate." Of course, this does not explain anything, nor is it supposed to. It is merely an articulated expression of our helplessness - intellectual, emotional and pragmatic - when we really come face to face with fate.

Someone might say, "But surely something can be done!" Yes, sometimes it can. However, whether something can be done in a particular situation is already a verdict of fate, which, at this moment, has left us some loopholes. Typically, we seek such loopholes, driven by the hope that maybe there is one. Sometimes we find one, sometimes not. Sometimes, however, we already know in advance that there is none and that all our bustling is just a differently articulated expression of our helplessness in the face of fate and its incredible chill. This chill is, after all, the emotional inhumanity of the universe reaching us in this way. It freezes us.

Czesław Miłosz saw this clearly. His major work, in my opinion, is "The Land of Ulro" (1977), which in his case means the land rid of all faith. And there we read (p. 194/5):

“If man evolved on earth by random mutation over billions of years, then attributing a benign will to the universe constitutes another version of religious mythmaking. To put it another way, (...) nothing binds human values to the inviolable laws of the universe (…) The positing of a human life in harmony with Nature, the cosmos, or universal Reasons merits as much credence as a belief in water nymphs and sprites (…) Man is alone; and if other planets are inhabited by beings endowed with intelligence, then they too are the product of chance, are just as alien to the universe.” [The Land of Ulro, translated by Louis Iribarne, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1984. p. 252-253]

Let us call the view of the world that emerges from these words by Miłosz tychism - a philosophy of fate. I share this tychism.

Stanisław Lem’s philosophy is also tychism. It is most clearly expressed in his statement for the monthly magazine Znak (7-8/1969) entitled "A philosopher’s vision on a floe", but also in all his later work.

The opposite of tychism is anthropism. It proclaims man’s superiority over fate or at least some kind of parity of the two in life. It is expressed in the well-known saying, "Man is the architect of his fortune." The opposition between these two views on fate was succinctly captured long ago, back in my youth, by my younger brother, later a renowned professor of theoretical physics. He said, "Man is not the architect of his fortune, only its bearer." Man doesn’t shape his fate; he simply bears it - better or worse, which, by the way, also depends on fate: on the nature it has assigned us and the incidents it sends our way.

3. The components of fate are not independent of each other. They do not stand one next to the other like trees grown next to one another: here, pure chance, there, the power of destiny. As Roman Suszko would say, they are connected by a certain dialectic: in what is accidental, destiny is involved, and in what is predestined, chance is involved. Let us call the "field of fate" this set of possibilities, the realisation of which, step by step, makes up our lives. In this field of fate, it draws a line, its trajectory, the course of which is determined by the "vectors" of destiny and chance. The dialectic is that these vectors are not orthogonal: they modify each other. The image of fate is thus obscured, but something is visible, nonetheless.

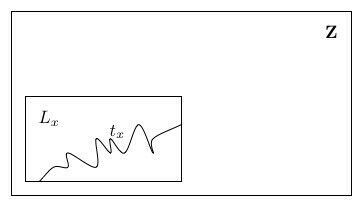

Above all, fate is individual: different mine from yours, still different his or hers. Of course, it also has elements common to all human beings. Together, they make up what is referred to as conditio humana, the "human plight". However, in addition to this common part, each of us also has our own, strictly individual part. Let us illustrate this important point with a simple diagram.

Let the rectangle Z represent the totality of life’s possible events: everything that can happen to anyone: "life’s space of possibilities". The points of this space represent different kinds of events: one - meeting a friend, another - missing a train, a third - a small theft; and so on. The fate of a given person X is a certain box LX , for each different one. (The cross-section of all fields is non-empty and denotes the common human plight of L =  .) The trajectory of X’s life lies in the field of their fate LX and may run there variously. Its actual course tX depends on chance, but never goes beyond this field. Across the field of fate LX, chance roams freely, but the boundaries to its roaming are set by destiny.

.) The trajectory of X’s life lies in the field of their fate LX and may run there variously. Its actual course tX depends on chance, but never goes beyond this field. Across the field of fate LX, chance roams freely, but the boundaries to its roaming are set by destiny.

This is how, for example, we commit various follies in life, many others we could commit. But there are some we know in advance that we would not commit, for that would be against our nature. Elzenberg states, "Destiny is just another name for our own nature." I turn this around and say our nature is just another name for destiny, another aspect of it.

It is said that "opportunity makes a thief." That is not true; it only reveals him. Opportunity is a chance that brings out the thieving nature hidden in someone – also for themselves, as before, they might not have been aware of it. "To steal when one can” – such an event must have already lain in the field of their fate by the force of destiny. For those in whose field it doesn’t lie, they will not steal, even if they could. Honesty is a burden of fate, like any other.

The diagram also shows how tychism differs from fatalism. Fatalism is a "point" tychism - extreme but strongly appealing to the imagination because of this. According to it, the trajectory of my life not only lies within the Z-field of life’s event space, which is closed by fate, but must also pass there through a specific point determined for me by "fate", which cannot be bypassed.

The legend of the Theban king Oedipus is the prototype of fatalism. He was prophesied by the Delphic oracle to kill his father and marry his own mother, i.e. to break two terrible taboos: patricide and incest. Oedipus did what he could to avoid the verdict of fate, and it happened as the oracle predicted. (Wanting to show this on a graph, it is enough to mark a certain point of distinction e In the Oedipus field Le. It must, of course, lie on the trajectory te and in the individually "Oedipal" part of this field: e є Le - L. All possible trajectories in the field Le then pass through this very point).

Tychism is a rationalised fatalism, purged of superstitious content such as astrology.

4. Destiny, rationally understood, limits the realm of chance. However, there is also a reverse dependence, and this constitutes another incredible trait of our fate. In the higher order of events - that which preceded us and will outlast us - our own destiny has been assigned to us by chance! To grasp this, let’s take a closer look at our destiny, at its rigid frame. What forms it?

The framework of our destiny is determined by three factors that are inherent and mutually independent: our genotype, our era, and our tribal community. In other words, what we were born as, when we were born, and among what kind of people we were born. (I explain that by "tribal community", also called "homeland", I mean something consisting of three great common things: a common speech, a common land and a common memory). Neither the genotype, era nor our community is a matter of our choice: each is a component of our destiny. The most important thing is the genotype.

The revolution in biology that took place in the second half of the 20th century revealed to what extent our genotype determines our phenotype: our entire individual physical and spiritual constitution - from health and appearance to intelligence, temperament, and character. Our genotype is our nature, and our nature is us.

It is not that "here I am, and there are my genes"; for these active genes of mine are me. The precursor of this consciousness was Nietzsche. In Zarathustra, he speaks of the "despisers of the body" (von den Verächtern des Leibes):

“To the despisers of the body will I speak my word. (...) The body is a great sagacity (eine grosse Vernunft), [and] an instrument of thy body is also thy little sagacity, my brother. „Ego,” sayest thou, and art proud of that word. But the greater thing - in which thou are unwilling to believe - is thy body with its big sagacity; it saith not „ego,” but doeth it (...) There is more sagacity in thy body than in thy best wisdom.” [Translation of Thomas Common]

A century later, Popper came to the same conclusion. In his The World of Propensity (1996, p. 56/7) we read:

"[A priori knowledge is] the kind of knowledge that an organism has prior to sense experience; it is, generally speaking, innate knowledge. (...) I believe that about 99% of the knowledge of all organisms is innate knowledge."

The new biology is changing our entire way of thinking about ourselves and the world. Lem was the first to understand it, but my arguments are also a symptom and consequence of this change. It goes in the direction of tychism. "Genes are power", says dentist Danuta Jędruszczak. She probably thinks mainly of her patients’ teeth, but she is generally right. You cannot win with a gene - not with someone else’s, not with your own. This applies to teeth as much as to character or intelligence. Their individual quality is our destiny; it cannot be improved.

The tychism of the new biology contradicts leftist pedagogy with its anthropic wantonness and criminal stupidity. They demagogically urge to "teach the youth not encyclopaedic knowledge but independent thinking" – although they have not provided a shred of evidence that it is possible. Independence of thought is a gift of fate, like cleverness or charm: either you have it, or you don’t. And this "activation of independent thinking", as they eloquently call it (cf. e.g. Maria Wanat-Goriaczko, "Głos polemiczny", Edukacja Filozoficzna 35/2003), practically amounts to egging the youth on to arrogance and impudence.

One thing must be acknowledged, however. In the unequal distribution of its gifts, fate reveals its third incredible feature. As someone said, "Fate does not know what morality is." (Roger Vailland’s The Strange Game, motto.) The opposites of the tychic and the anthropic attitudes are drawn most sharply at this point: the right-handed acceptance of fate and the left-handed opposition to fate. Which of these attitudes is rational, and which is irrational? Around this issue, there is a dispute and battle in the Western world.

5. A digression here, but an important one. They ask foolishly: when in foetal life does a human being begin? They ask ignorantly or deceitfully because the answer is simple: it starts at conception, i.e. with the zygote! It is created by an incredible explosion of vital energy released by the fusion of two haploid cells - the paternal sperm with the maternal egg - into one diploid cell, called a "zygote". It is this explosion that throws us into existence and determines our destiny - starting with sex. If a pair of XX chromosomes fused, it produced a girl; if a pair of XY, it produced a boy. These, in turn, are two destinies supremely different, indeed two varieties of humanity.

In the zygote, our soul is already present, although still dormant - like in anaesthesia. Our entire intellectual, emotional, and moral individuality is written in the language of the genotype. We all started from a zygote, for it was not birth that created us after all, nor a caesarean section.

Conception is the "zero" moment in our lives from which our counter runs. Questioning this fundamental fact is either wicked sophistry or plain ignorance.

6. The genotype - that which is innate and fixed - is the dominant feature of our personality and our destiny. However, it does not alone determine them.

In personality, I distinguish three layers of its susceptibility to the influence of the environment: external α - socially flexible, which is shaped easily; intermediate β - socially malleable, which is shaped with difficulty; and internalg - socially rigid, which cannot be shaped at all.

The shape of the α layer – let’s call it "adaptive" - is directly enforced by the social pressures of the environment, its ad hoc sanctions. (For example: a student speaks impudently to the teacher. A single reprimand, and he knows how to speak. The α layer in him changed instantly.) The α layer is as resilient as a ball: its social deformation continues as long as the social force σ that forms it presses on the personality: as long as the real threat of sanction continues. Once it is subtracted, the personality immediately returns to its inherent shape: to a "state of nature" - as Hobbes would say - in which human life is “nasty, brutish, and short.”

Layer α is the awareness of the social rules of the game induced by the fear of sanctions for breaking them. Living in a group, the individual must comply with its rules because he sees that the group is physically and morally stronger than him; and will not win against it.

It is different with the β layer. This one forms permanently, like iron under a hammer. It bends much harder than the α layer, but once it bends, it stays. This is what the "ductility" of any material is all about. Layer β consists of personality traits acquired, mostly in childhood. They consist of reflexes implemented by social training, i.e. prolonged and unidirectional pressure from the environment, as well as habits acquired automatically by imitating the prevailing custom: "Others do it, so do I". (An obvious example is our mother tongue.) In the β layer also lie our manners and tastes. In general, everything that is called "civilisation" and opposes "barbarism" and "savagery" lies in it. The shape of the β layer makes certain behaviours "unthinkable" for us.

I call the β layer "civilisational". It is part of our destiny because it is formed by the other two factors of our destiny: the epoch in which we have lived and the community into which we have grown up. Max Weber states, "Differences of culture and taste are the most difficult state barriers to overcome." It seems doubtful to me whether they can be overcome at all in a single generation.

Layer g depends only on the genotype and is the nucleus of the personality. It contains our entire disposition. It also determines the degree to which an individual’s α and β layers are susceptible to environmental influences. (Because the degree of this – "social susceptibility" - is, of course, also individually different.)

The nucleus g is impervious to social influence. It is not moved by requests or threats, persuasion or manipulation: it is as hard as a diamond. It can be shattered; it cannot be bent. At moment "zero" it was defined by the sentence of fate: "such - or such - you will be"; timid or bold, truthful or deceitful, independent in thought or imitative - and so on through all the coordinates of the human disposition. To want to change this judgment is to argue futilely with fate. The tendency to such disputes - if there is one - was also already written in layer g. No one can step outside the field of their fate.

Stratum g changes only population-wise. That is: the elimination of carriers of certain genes can cause their proportion in the gene pool of a population to change. This is how, for example, the various breeds of dogs have arisen - all from the domesticated wolf, over ten thousand years. The eminent Soviet geneticist Nikolai Vavilov, who later (1943) perished in the depths of the Gulag, said in the era of Lysenkoism: "Natural selection of people without the gene of decency is carried out in science." (В науке происходит отбор людей без гена порядочности.) And what is it like today?

Our genotype is recorded in the zygote as a double, "diploid" set of chromosomes: 23 from the father and 23 from the mother, making a total of 46. It is then duplicated by all the cells of the organism. In how this set is formed, one can best see the other amazing feature of fate already mentioned: its lottery nature.

The reproductive cells are collectively called "gametes": a zygote is the union of two gametes. In a gamete, the set of chromosomes is single, "haploid": it only counts 23 of them and is then called the "genome". Our genotype is a combination of two genomes, maternal and paternal.

The organism produces gametes from normal diploid cells in a process called "meiosis", or "reduction" (meion meaning less). This process - beautiful in its combinatoriality - produces many different genomes from a single genotype: 223, so about ten million, each genome different. The conditional probability that, given parents, exactly our genotype will be assembled from their genomes is negligible: it is (1/223)2 , so about one hundred millionth.

Choosing from this vast urn of genotypes just this one of ours was a great accident in the lottery of life. It determined our personality, its quality and value, and, along with them, our destiny. It randomly picked us and our destiny from countless other possibilities, like a game of chance.

There is something in the immense randomness of our fate that amazes and disturbs - though perhaps it shouldn’t, because after all, what’s so special about it: a lottery is a lottery, only bigger than one might have thought. And yet, there is something disturbing here. This insight into the genetic mechanism of our fate seems both wonderful and frightening at the same time, something - as Paweł Hertz put it - no longer tailored to our measure.

8. And where is free will? There it is too - where fate gives us free will: in the field Lx. As we move along the trajectory of life tx , we hit what I call "crossroads" situations - like this point s in the figure:

These situations present us with a choice between two unfolding possibilities, facing the alternative of "p or p’ ": bet on red or black in Monte Carlo; accept his proposal or reject it; travel to Smolensk by train or by plane. Here, we decide, not fate; even though it is fate that provides us with the choice, it is not we. From the standpoint of tychism, free choice is a peculiar kind of chance. Marian Smoluchowski defined "chance" as an event in which a "small cause brings about great effects": it is energetically disproportionate. In a crossroads situation, such a "small cause" will be our act of choice, meaning ourselves. Let’s stick to Smoluchowski’s famous formula.

Destiny does not exclude free will; it only limits it. Some find it difficult to come to terms with such a stranglehold and seek a remedy in "positive thinking", or spin mirages of a life without end thanks to transplants (like Zbigniew Religa before he died). They have even invented a new quasi-scientific principle - they call it the "anthropic principle" - according to which the world is arranged specifically for us, and we are its “hosts” (Kim Ir Sen, Jerzy Buzek). Others embrace trees to absorb their longevity or, for the same purpose, allow themselves to be buried up to their neck in the ground, which they then call "Gaia" in Greek.

Anthropism - the notion that man is the master of his destiny - is an expression of rampant egotism and megalomania, robbing people of their reason.

9. Tychism is the conviction that man is s u b j e c t to fate. How does it relate to Christianity?

It depends to which one, because there is a left-leaning Christianity - anthropic, and there is a right-leaning Christianity - tychist; although the former prevails today. This is most easily seen in the differently conceived the role of the Church. Anthropic believers say, "The Church serves man", and they believe they have praised man for that. Tychist believers say, "The Church serves not man but the glory of God", which the former cannot understand because they are anthropic. "Man" is the "highest value" for them, and everything should serve man; probably including God.

Tychist Christianity traces its lineage back to St Augustine (354 - 430), from his doctrine of grace. Anthropic Christianity, on the other hand, has its ancestor in Joachim de Fiore (1132 - 1202) and his announcement of man’s equality with God. Currently, this idea is embodied by swarms of Christian progressives - from "liberation theology" to Father Tischner and his spiritual counterparts.

According to Augustine, it is not because someone has lived God’s way that they are saved; on the contrary: he lives God’s way because he has already been saved - before he was born. Grace descends upon us like destiny. In today’s terms, we can say that we are either saved or condemned already in the zygote by God’s judgements, which are as inscrutable as the judgements of fate.

Tychism also has another, more general connection with Christianity. Hegel rightly said, "Religion begins with the awareness that there is something higher than man. Fate is higher. Therefore, the idea of fate is a religious idea."

10. Towards the end of Elzenberg’s life, Tadeusz Czeżowski visited him in the Warsaw hospital on Spartańska Street. During one of these visits, he told Elzenberg in his spirit and style, "A year later, a year earlier - what’s the difference?" to which Elzenberg was indignant. It was Czeżowski who was a tychist thinker - the "Roman stoic", as Kotarbiński called him - not Elzenberg. He had other advantages, significant ones, just not this particular one.

The moral of this hospital parable is this: anthropism and tychism are not two views. They are two types of personality: type A and type T. To put it after Kant, they are two opposite regulative principles of our thinking about life and the world. Such principles are not chosen by anyone; they are assigned to us by fate - already in the zygote. We have them not in our heads but in our guts, like our blood type or right- or left-handedness. At most, we can only become aware of our regulative principle; it is not in our power to change it, nor is it in the power of anyone’s persuasion or argument. For this principle is us, our fate.

* First edition of the article published in Edukacja Filozoficzna vol. 50/ 2010.

Read also

Freedom of Speech in Western Civilisation

The subject is difficult because it touches on the idea of freedom. And this idea in itself harbours antinomies that are not easy to resolve.

Comments (0)